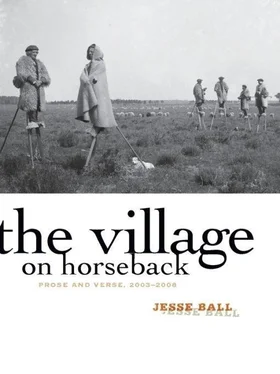

Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Milkweed Editions, Жанр: Современная проза, Поэзия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

- Автор:

- Издательство:Milkweed Editions

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness

The Way Through Doors,

New Yorker’s

The Village on Horseback

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The third:

A grand theatre, built to hold an audience of all that were ever born and all that will ever die, but the arriving there has taken place far too soon, and no one has come. Then, the wandering up and down aisles, empty aisles, the choosing of a seat from thousands made thousands in the thousandth part. Balconies, boxes, side-seats, hiding places on the roof, stools set on the stage-side, chairs built into the machinery of the lamps and bells and curtains.

Alone there and walking and walking, sitting first in one chair and then another, whistling and singing. Speaking first softly, and afterwards with a loud voice, for it is no matter. No one has come. One is far too early for the proceeding of life, even in one’s own body.

To arrive too early even to live in one’s own body.

And then sleep again.

That was the third dream.

The fourth dream:

As though in morning, with little warning, a yellow-haired man came in through the window.

Pieter Emily rose in his small room. In his house there were but two rooms. He went into the other and lit the stove. The yellow-haired man was already there.

The yellow-haired man was standing at once in all the rooms of the house, standing at once in every field, upon every roof, sitting in the boughs of every tree, prone upon each running stream, each still lake.

You cannot escape me, said the yellow-haired man.

But all at once, there were two countries, then three, then four, then five, and Pieter Emily and his cottage were nowhere to be found, and search as the sun might, its rays were like arms without hands, and could not lift the earth to see what lay beneath.

That was the fourth dream.

Yes, Elsbeth woke and looked about her. The room was there, with the full light pouring through the windows, and the loom at the room’s center, strung like a harp, finer than ever. She sat at it, and felt the shuttle and how it sat upon her hand.

Then a knocking at the door.

— Elsbeth, will you come?

She rose and went to the door. Pieter was there.

— I must speak with you, he said.

Then they walked together the length of the house.

— Elsbeth Grimmer, said Pieter, and he looked at her but said no more.

He wants me to live here, thought Elsbeth.

And she thought of the loom, and how she had never seen a loom so fine. She thought of the feel of the place, like a house in a well to which no one can ever come. She could live here, she thought, and pass her days in weaving just as she would in town.

— Do you like the loom? he asked.

And she felt the truth of it. To leave her sister’s house, to leave her shop, to leave the town. . She could.

Elsbeth opened one of the narrow windows and leaned out so that the land beyond was all about her, the hill and the house and the room behind.

I will live here, she thought to herself.

And Pieter nodded.

— You have had many dreams this night, said Pieter. If you like I will tell you the meaning of one, but only of one.

— This was the dream, said Elsbeth. I had lost my legs in a threshing accident, and instead of legs I wore long stilts buckled to my knees. On these stilts I could make speed through the fields and so I was a carrier of messages like no other. My father was a wealthy farmer, a prince of sorts, and all those merchants who came to him would speak and wonder at the beauty of his broken child fluttering above the wheat on legs of wood. Call to me, I would say, call to me, but none would call. None called, and when my father grew old, the farm was mine, and I wore a leather coat and carried a sling and kept a watch over the fields in the long night.

— What you invent, said Pieter, is as telling as a dream.

— Do you say so? asked Elsbeth.

— The threshing accident was birth, the wooden legs the loom. Your father is the town, the messages the needs perceptible to you in thread. Those visitors are nothing, the mountains beyond. You have no hope of them, and never did. The leather coat, the sling, are a step with the left foot and the right as you come here to me to speak not in defense of myself, but to protect your childhood which seems now so far.

— And yet, said he, it is the good fortune I have awaited, so we shall call it what you like.

The day was early still, and the sun beneath its zenith. Pieter and Elsbeth went to the hill’s edge, where there was a well and a stone wall. The grass on either side of the stone wall was alike. It began and ended with no purpose.

— What is the purpose of this wall? asked Elsbeth.

— I built this wall, said Pieter, twenty years ago when I built the house, thinking of the day when we would walk out from the house and need a place to sit as I told you the necessities of your return.

Elsbeth smiled a smile of not-believing.

Then Pieter sat in a way that said, you need not believe me, but still it is true.

— You’ll go then back to the town to fetch some things. But if you are to come and live here, you must obey these few things.

He looked sharply into Elsbeth’s eyes.

— You must bring back no iron.

— You must say my name to no one, and say nothing of what you have seen.

— You must not sit in a chair or upon the ground when you are again in the town. Neither can you take food or drink.

— You must return here before the sun goes down, and you must bring back no more than you can carry in a single bag. There will be a new life for you here, with as many things as you desire. These things that you will bring will be the last of your old life.

Elsbeth nodded.

— And you must not be cut, or let a drop of blood out of you in the town. There is time still today. Go and return.

Elsbeth stood.

— I will bring no iron, she said. I will sit nowhere. I will say nothing of what I have seen. I will take no drink, no food. I will return before sunset, and I will take but a single bag. No blood will come from me while I am in the town.

Pieter wore a long coat of harsh canvas, buttoned on the side, and he had at his side a long knife.

— What will you do, asked Elsbeth, while I am gone?

— I’ll check on my field, give food to my animals, and set out in the woods.

— You must be here when I return, said Elsbeth.

— Have no fear of that, said Pieter, for I know every way in the wood, and can judge time from the limbs of trees.

Then they were parted, and Elsbeth rode away into the town, and when she looked back from a rise in the road what she saw behind her was a burned-out cottage on a ravaged hill, and she found that her clothes were dirty, as though she had slept the night on a bed of ashes.

|||||

After a short ride, Elsbeth reached the town. She saw it from a distance, its intricacy of wood and walkways, its rising of turrets and workshops. Smoke rose from dozens of chimneys, people leaned out windows. The warmth of the sun was here though it had not been with them on the hillside at the reasonless wall.

— Will I go back? asked Elsbeth. And then she thought of the loom, and her blood stirred.

I can, she thought, always return to the town one day. If I like, I can return after a month, after a week. I need not stay with Pieter forever.

But she saw in his face a hardness and she knew that what was binding to him would be binding to her.

At the stable she left the horse, and went on home.

Moll Ongar stopped her at a crossing.

— Elsbeth, she cried out. Elsbeth have you heard?

— What is it, Moll?

Moll’s face was red with the news.

— The mayor, squeaked Moll, Falk’s hand was cut off at the wrist. He reached into a cupboard and when he pulled his arm out there was blood everywhere. I mean, they brought in the body of Pieter Emily today, and hung it on the gate. I said so myself, I said it was bad luck, and now see what’s happened.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.