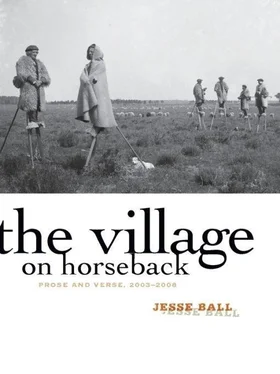

Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Milkweed Editions, Жанр: Современная проза, Поэзия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

- Автор:

- Издательство:Milkweed Editions

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness

The Way Through Doors,

New Yorker’s

The Village on Horseback

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She called to Lubeck from across the room.

— You won’t fail us, will you, John?

— There’s nothing to do, said Lubeck, standing up, still looking out the window. There’s nothing to do.

— That’s right, said his mother. It’s the only thing.

She looked them one by one, Brennan, Carr, Harp, full in the face.

— A thing like that, she said. It’s awful. There’s no choice in the matter. You’ve got to have it out or we can’t live in this town.

Lubeck’s brothers and sisters had come into the room. There were perhaps eight of them of various sorts and ages. Lubeck’s stepfather also had come in.

— A bad business, a bad business, he said, and pulled at his moustache. Seems to me you deserve what you get.

— That’s right, said Lubeck’s mother.

— These days, what with automobiles and propeller airplanes, the power of man is getting stronger and stronger, said Lubeck’s stepfather. If he doesn’t learn some moral strength, it’ll all be as unjointed as a scarecrow.

— I don’t even know what you’re saying, said Lubeck.

— Suit yourself, said Lubeck’s stepfather.

— This is a very very bad thing, said Brennan.

— It’s a very bad thing, all right, said Lubeck’s mother.

The next morning, Carr went with Lubeck. Brennan had refused, and though Harp had wanted to come, Lubeck wouldn’t have it.

— You’ve got to come along, Lubeck had told Carr. Just you.

They took Lubeck’s stepfather’s automobile, and drove out from the town. The morning light where the snow still held was strong in their eyes, and they squinted as they came.

Soon they reached the track. A car could be seen through the bare trees, and a few figures beside it.

Lubeck pulled in and stopped the engine.

— The pistols are there, the man said.

He was as old as the Judge. Both wore overcoats over dark suits. Both wore hats and thin leather gloves. They had laid a soft cloth over a portion of the car’s hood. On the cloth were two revolvers. The scene was very dignified. One would want, as a child, to be old enough to take part in such a thing, to be there in the heaving coldness of morning, in the careful grace of winter, though of course, the true penalty of death cannot be considered in its depth by such a little fool as a child. No, no.

— Either, said the Judge.

— What?

— You can take either.

The Judge’s second walked out and drew two lines in the earth of the cinder track, about twenty feet apart. He called Carr over.

— The way this thing is going to get done, well, this is it. Lubeck and Judge Henry will wait, each some yards behind their line. At our word, each approaches his line. When the line is reached, they begin to fire.

— How many shots can they. .?

— Eight in each revolver. If they both run out, we start again.

He looked at Carr with disgust.

— You were with him, weren’t you? You’re one of them?

— I, well. .

The man turned his back on Carr and approached the place where the Judge was waiting.

— All set, he said.

Judge Henry motioned to Lubeck to take a pistol from the hood. Lubeck hesitated, then chose, lifting the gun uncertainly.

Carr was at his side. They took a few steps together away from the others.

— You can leave. You don’t have to do this, he said quietly. Leave the town. Leave the country.

Lubeck looked at him and away.

— Tell them I’m ready.

— To your posts, said the Judge’s second.

The Judge and Lubeck stepped out onto the track.

Carr felt as if someone were squeezing all the air out of his body. Things became slow and strained. He heard the man call “NOW!” and watched as Lubeck and the Judge advanced, step by step. Near the lines, they raised their pistols. They pointed their pistols at each other. Carr couldn’t breathe. He was held there, without breath, as the shots began. Lubeck fired and fired. The Judge fired, fired again. Both continued advancing. The noise was incredible. He felt he had never heard anything so loud. Lubeck fired and the Judge flinched, and then they were just walking at each other, just walking. The Judge let out three shots in a row.

The shots just poured from his revolver. Lubeck was not firing. His face was turned away. The first shot came. The second shot came. The third shot came, and Lubeck was backwards off his feet.

Carr ran out onto the track. He slowed his pace as he drew closer. The bullet had taken Lubeck high in the cheek and gone straight through his head. The face was a bloody wreck. He was no longer there.

Carr realized he had started to breathe again. He turned. The Judge and his second were conferring. The second came over, passed Carr, knelt by Lubeck’s body. He was taking the pistol back. He removed the pistol from Lubeck’s hand, opened it, dropped the spent shells on the ground, and walked away.

Then he paused.

— You, he said. Give this to Brennan.

He was holding a letter.

Across the length of track, the Judge was looking straight into Carr’s eye. His face was carved like a mask of a face.

the third

~ ~ ~

Carr drove very gently along the road. He had found soft leather driving gloves on the dash and he had put them on and now he was driving gently. He negotiated one turn then another. He was bringing Lubeck’s mother her son’s body. Such a thing he had never done, but he felt it was within him to do it.

Lubeck was stretched out in the back seat. Carr had wrapped his head in a sack. Other than that, he might have been asleep. One often, however, can take the sign of a bag over a person’s head to mean that something bad has either happened or will happen. So, anyone observing the scene would not have to wonder for very long at the difficulties that were assailing young Carr as he drove gently on the twisting road back into town.

Over a small bridge and down by the harbor. Along an alley and stopped beside a huge oak. Then, to the door.

Come out, he said. Come out.

They came out, many of them, a crowd of them, all down to the road where Lubeck was. Carr went gently away.

Do you know the surface of the stream? Do you know its depth? Do you see as fish see, that water is not one but many, that there are paths through it, just as through land, and that to pass along a stream is a matter well beyond the powers of any human being?

Carr was reading from a thin book. He was still near the harbor, on a bench. He felt that he could not leave without giving Brennan the letter. But he did not want to.

A little girl was there with a cygnet on a narrow leather leash. She drew near and looked at Carr. Carr looked at her.

— When it grows up, it will do its best to hurt you, he said. I know that much.

— Her name is Absinthe, said the girl. And I’m Jane Charon.

— Nice to meet you, Jane.

— Not so nice for me, said Jane stoutly. You say such horrible things.

— I saw a swan maul a child once, said Carr. The child had to be removed. To the hospital, I mean. The swan was beaten to death with a stick.

Jane covered the cygnet’s ears. You’ll have to imagine for yourself what that looked like. I don’t really know where a bird’s ears are.

— But, said Jane. If you were there, why didn’t you help the child?

— Sometimes, when you see something awful about to happen, although you are a good person and mean everything for the best, you hope still that the bad thing will happen. You watch and hope that the awful thing will happen and that you will see it. Then when it happens you are surprised and shocked and pretend about how you didn’t want it to happen. But really you did. It was that way with me and the swan.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.