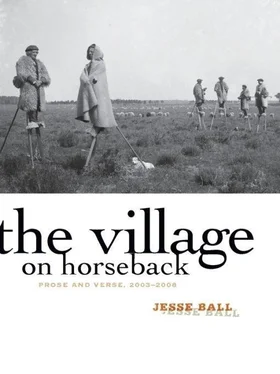

Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Milkweed Editions, Жанр: Современная проза, Поэзия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

- Автор:

- Издательство:Milkweed Editions

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness

The Way Through Doors,

New Yorker’s

The Village on Horseback

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

— Where is the body? asked Elsbeth.

— The main gate.

Elsbeth stood looking up at the arch. There was blood there, where the hook was, but no body.

Took him down an hour ago.

— What?

Elsbeth turned.

— What did you say?

An old man was sitting there in the shade.

— I said they took him down an hour ago. I’ve been sitting here all day. I watched them bring him, watched them hang him up, and I watched them come an hour ago, take him down and drag him off to burial.

— Where would that be? asked Elsbeth.

— Where do you suppose? asked the old man.

He spat on the ground.

— I don’t know, said Elsbeth, the graveyard?

— Would you want him there? asked the old man, with decent folk?

Elsbeth narrowed her eyes.

— Where are they burying him?

— Why do you care anyway? said the man suspiciously.

Another old man came out of the inn and sat down on the bench next to the first old man.

What’s the news? he said.

— This woman’s wanting to know where they took Jansen’s son.

— Jansen’s son?

— Yeah, where they took him.

— Doesn’t she know that?

— Seems not.

The second old man looked up at Elsbeth.

— Haven’t seen you in a time, he said. Elsbeth Grinner. My son says the shops been closed last few days.

— Clef Carr, tell me this minute, said Elsbeth. Where is Pieter Emily being buried?

— Buried him already, said Carr. In a plot by the church, face down like a suicide, from shame.

No one was at the house when she arrived. Elsbeth went up to her room and laid out a bag. She changed her dirty dress for another, and filled the bag with a few things, then a few more. She set out all she’d like to take with her, and saw that it was more than would fit in the one bag.

— I could take two, she said. Two would not be so bad. He couldn’t object to two.

But when she left the room, it was with the one bag, and having left the best of her things behind.

On the stairs, she heard the door creak. Catha came in.

— Elsbeth, she said. Elsbeth, where have you been?

And Elsbeth looked at her and said nothing.

— Elsbeth, she said, where have you been?

— I went, said Elsbeth, to the mountain pass, to see if it’s clear, to see if anyone come from the outside.

Catha shook her head.

— That’s a lie, she said. What are you doing with that sack? Where are you going now all dressed to travel?

Elsbeth looked at her feet.

— What’s going on? said Catha. Last night I dreamt the strangest dreams, so clear I could remember all when I woke. And when I did, I went to your room to tell you, for I know you had the same, but you were not there, and your bed was made.

— What did you dream? asked Elsbeth.

— I dreamed of a opera house like the ones in the great cities of the East, a grand place, as large as a city itself, and made to hold all that were ever born, or ever will be. Yet it was morning, and the opera is an evening’s word. It was morning and I came there all alone to walk among the seats as through a forest of pines, where the needles make a bed and all’s quiet. There were no hands to hold, and so I held my own and went through the arcades, the balconies, the anterooms, calling out, but no one came. The roof of the opera was painted like the sky, and changed like the sky, changing as I moved, and ceasing when I ceased. All the lights were lit, great lamps burning at every interval, in every unpeopled room. I felt that you were there, that you had been there.

Said Elsbeth,

— I was there, with you, and you with me, but we could be no comfort to each other.

— And this? asked Catha, her hand taking in the sack, the traveling clothes.

— There’s no comfort for me here, said Elsbeth, only craft and continuing.

— Do you know, said Catha, taking her sister in an embrace, that they killed him?

Catha began to cry.

— They killed him, she said, and hung him on the gate.

To this Elsbeth said nothing.

— Where have you been? asked Catha. Oh, you will not tell me. Then go, and go, and I shall watch you from behind your shoulder, as I always have.

— And I you, said Elsbeth.

On the stoop she set down her sack, for a thought had pricked her. What of iron had she taken unwittingly?

And from her sack she drew a penknife, from her sack she drew three needles, from her sack she drew a scissor, all gone there unknown.

She left these on the doorstep, and made to go. But Catha called to her from the door.

— Are you not hungry? Let me make you a meal before you go. Let us sit and have a drink.

And in Elsbeth then a hunger greater than she had ever felt. Yet she dismissed it. Then in Elsbeth a thirst as for the sea.

He said no food and drink. To have one drink alone. . It might be all right. She went into the house, and Catha poured a glass and a glass of wine.

— Sit, said Catha.

— Oh, said Elsbeth, I cannot.

And she turned away from her sister, standing there with the two glasses.

— Goodbye.

Then she fled through the door, and as she did a nail caught at her.

Her sleeve tore and the nail was against her skin. But it did not cut.

Elsbeth breathed and closed her eyes.

— Goodbye, she said again.

And then she was out in the day and the day was soon to finish. Bag over her shoulder, she made her way down to the stable. I will go another way, she thought, than the usual. I do not want to see anyone at all.

So she took the alley behind the main street, and went along behind shops and houses. As she drew near the stable and the town’s edge, a voice called out.

— Elsbeth. Elsbeth Grinner.

She turned. It was the priest.

— Father, she said.

— My daughter, what ails you?

He came up, Father Rutlin, and took her chin in his hand.

— What ails you? he said.

— I am as well as I may be, said Elsbeth.

She tried to pull away, but he would not let her.

— Elsbeth, he said, Elsbeth, there is a skin on you. Another skin, that you cannot see.

He ran his hand over her face and along her arm.

— There is another skin. It is between you and the world. I shall take it away.

— No, said Elsbeth. Do nothing!

But Rutlin held his hands at her temples and spoke beneath his breath, and when he let her go, he drew something off her that left her weak in the legs and arms.

— Come tomorrow, said Rutlin, I demand it.

And he fixed her with his eye.

The light of the sun was lying on its side and coming here and there through the houses and walls.

Elsbeth looked helplessly back and then broke away.

— Elsbeth, he called. Come tomorrow. Heed me.

||||||

On down the road on horse, on horse down the low road as the road sank and the sun sank, and a weight was upon her.

He must let me in, she thought. He must.

On she went, and evening drew near. Yet as she came down the side of the last hill, the sun was in the sky, still above the trees.

I am in time, she thought, and she urged the horse on.

The cottage appeared before her in ashes, as it had been. It lay ahead, in ashes. Up the hill she came, and down from the horse. The cottage was in ashes.

— Change, she thought. Change. Flicker and be here.

But she came on horse, and then she came on foot to the cottage, and the ground was ash. The cottage was ash. She walked about in the ashes, and moved them with her feet. The horse went off to graze where it had been the morning before. And the sun was gone from the sky, and she laid down in the ash and wept, and fell into sleep, and this is what she dreamed:

She was sitting at the loom, the black loom, strung as it had been by her the night before. She began to weave, and she wove faster and faster, and the room began to spin. She wove and she wove and a pattern grew, and she could see what it was in the pattern, rising from her hand.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.