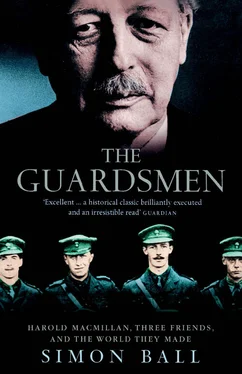

The Guardsmen

Harold Macmillan, Three Friends, and the World They Made

Simon Ball

To Helen

Cover Page

Title Page The Guardsmen Harold Macmillan, Three Friends, and the World They Made Simon Ball

SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PREFACE

1 Sons

2 Grenadiers

3 Bottle-washers

4 Anti-fascists

5 Glamour Boys

6 Churchillians

7 Tories

8 Ministers

9 Successors

10 Enemies

11 Relics

CONCLUSION

NOTES AND REFERENCES

INDEX

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Until recently, a book of this kind could not have been written. It is only in the past decade that the archival materials to make it possible have entered the public domain. We now have a critical mass of papers, produced by the four principals of this story, allowing us to understand their thoughts and actions in detail.

Harold Macmillan wrote prolifically on his own life. He also inspired a number of biographies, culminating in Alistair Horne’s official two-volume life completed in 1989. Underlying both Macmillan’s autobiography and Horne’s biography were Macmillan’s voluminous diaries. These diaries are now open for inspection at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. There are two versions of the diary: the original hand-written volumes and an edited and typed copy Macmillan subsequently had made up. Both versions are used in this book. Also in the Bodleian is a collection of letters Macmillan wrote to his friend Ava Waverley, which, in some cases, served as first drafts for his memoirs. The diaries are a magnificent historical source. Indeed they will, when published, endure as Macmillan’s best and most important contribution to literature. They must nevertheless be treated with some caution. Macmillan did not keep a diary simply for his own amusement. His diaries were always meant to be read by others. In the first instance he wrote diary letters to his mother and later to his wife. These diaries were shown around the family and the Macmillan circle, including political acquaintances. By the time Macmillan started his continuous ‘political diary’ in 1951, he was a very self-aware recorder of events. The later diaries were kept with the sensibility of memoirist. Macmillan’s explanation of events, and in particular of his own motivations, was thus both an immediate reaction and a footnote for the future. Such self-conscious writing loses nothing in value yet needs to be read for what it is – self-justification rather than justification of the self. Horne’s fine biography, which I have used extensively, can be criticized for taking Macmillan a little too much at his own valuation.

Potentially as important a part of the Macmillan collection at the Bodleian is his political correspondence. This book draws on the Stockton constituency correspondence written between 1924 and 1945. Much of this correspondence is ephemera. There are, however, letters which reflect on wider political events. Those letters dealing with the minutiae of politics are much less self-conscious than the diaries and have the value of immediacy. Of value for the same reason are the diaries of Cuthbert Headlam, which have been published in an expertly edited two-volume edition by Stuart Ball. Headlam’s diary is a goldmine, for he not only knew Macmillan well, but also Crookshank and Lyttelton. In 1915 Headlam and Lyttelton served together as aides-de-camp to Lord Cavan. After the First World War Headlam entered Parliament at the same election as Macmillan and Crookshank in 1924. Headlam’s seat, Barnard Castle, abutted Macmillan’s in Stockton. They were political allies in the 1920s. Along with the constituency letters, Headlam’s diary allows one to reconstruct Macmillan’s early political trajectory from contemporary sources rather than relying solely on his own memoirs.

Oliver Lyttelton ranks second to Macmillan as a memoirist in volume of output. He published volumes of autobiography in 1962 and 1968. During the same period he was involved with the foundation of Churchill College, Cambridge, as a memorial to his leader and friend, Winston Churchill. He left his papers, and those of his mother and father, to the college as the Chandos Papers. The collection is thus particularly rich for Lyttelton’s early life – to the point when he left the army in 1918. These early letters formed the basis for his own 1968 volume, From Peace to War. He published most of the letters he wrote to his mother during the First World War, lightly edited, in that volume. When Lyttelton decided to remain in public life after 1945, he started a collection of political papers. The papers relating to the intervening period are exiguous. This gap has had to be filled using papers from other sources. Most obviously, Lyttelton’s official papers relating to his ministerial offices – President of the Board of Trade, Minister Resident in Cairo, Minister of Production and colonial secretary – are to be found in the Public Record Office, Kew. In the inter-war years, however, Lyttelton was businessman rather than public servant. With the indispensable help of Mr Andrew Green, company secretary of the Amalgamated Metal Corporation, the company Lyttelton founded in 1929, I tracked down Lyttleton’s business archive. Now part of AMC’s non-current archive, the papers were housed in a storage warehouse in Docklands. As a result of Mr Green’s kindness I was able to extract these papers and examine them. As Lyttelton became a prominent business leader in the 1930s, he starts to appear also in the official papers of the Board of Trade. There are also papers relating to Lyttelton’s post-war business career in the archives of GEC, the company that took over Lyttelton’s AEI in 1967.

In contrast to Lyttelton and Macmillan, Harry Crookshank published no memoirs and next to nothing has been written about his life. The only extended appreciation in print was published by Lyttelton in the Dictionary of National Biography. In fact Crookshank, like Macmillan, was a formidable diarist. By the time the Macmillan papers arrived at the Bodleian, the library had long since bought Crookshank’s diaries, covering the years 1934 to 1961, at auction. These diaries have over the years been read by a small number of historians interested in the political events upon which they touch. They receive only passing references in most secondary literature. There is a very good reason for this. Unlike his closest friend, Macmillan, Crookshank was a true diarist. He kept his diaries for himself rather than for posterity. They are thus concerned largely with the mundane and the quotidian. If one wished to understand Lincolnshire weather patterns in the age of appeasement, Crookshank’s diaries are the place to look. The diaries have thus proved a grave disappointment to political historians. This may be one of the reasons why so few have a good word for their author. They are even so a treasure trove of information for anyone interested in Harry Crookshank himself.

Indeed, Crookshank’s concern for recording the events of his life went even further than his diaries. He, his mother and his sister maintained massive scrapbooks of cuttings regarding his life and career, starting with items pertaining to the Crookshank family going back into the nineteenth century. These books have found their way into Lincolnshire Record Office. The coverage of Crookshank’s life in these two sources is fairly complete. A search of the archives of the Grenadier Guards, greatly assisted by the staff of Royal Headquarters, Wellington Barracks, then yielded a missing segment of the Crookshank diary. As well as the later political and personal diary, Crookshank kept a very full war diary covering his military service on the Western Front and in the Balkans between 1915 and 1917. In contravention to all regulations, he wrote up regular entries in his pocketbook when he was on active service. Whenever he returned to London he wrote out these pocketbook diaries, adding detail, into desk diaries. At some later stage, probably in the 1920s, he inter-polated typed recollections into the desk diaries. Crookshank also wrote an account of his diplomatic career in long letters to his friend and fellow diplomat Paul Emrys-Evans, whose papers are held by the British Library.

Читать дальше