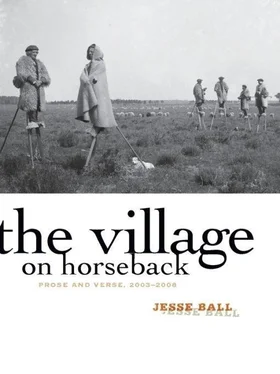

Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Milkweed Editions, Жанр: Современная проза, Поэзия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

- Автор:

- Издательство:Milkweed Editions

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness

The Way Through Doors,

New Yorker’s

The Village on Horseback

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

— But where is he? asked Elsbeth.

Pieter stood and a shadow passed over his face.

— He grew sick, he grew sick one day, and there was nothing could be done. He was dead by nightfall. I buried him out on the hill, with a stone for a pillow, and a name scriven on the stone and set beneath the ground.

— There was grief too in the town, when the child disappeared, said Elsbeth.

Pieter looked up and an unpleasant smile grew on his face.

— I think less of grief in the town, he said. Shall I tell you another story? A man goes walking in the woods and he meets another man, who he vaguely knows. He is guarded in his manner, perhaps even frightened. He has a weapon of some kind in his coat. He longs to have it in his hand, but there is no time for that, the strange man would see him reaching in his coat, would wonder why. And so they stand there talking and talking. I must get back to the farm, says the man. There is much work to be done. But the strange man lifts his hand. No, he says. No. No work now to be done, but you shall come walking with me. And so the men go walking further and further into the wood, and the wood changes. It changes from being of this year to being of another year, of no year. Do not leave me here, says the one. For I do not know the way back. But already the other is gone.

Elsbeth drank from her cup and the tea was hot and filled her with the far scent of oaks and trees in the deep wood.

She felt at once glad and safe, and also as if standing on a thin rope high above a flat country.

What am I doing here? she asked herself.

— I am sorry, she said, that I was no help to you when you fled the town. No one knew where you went, or even if you lived.

— Too long, he said. Too long ago to speak of.

— But they are speaking of it now in the town, said Elsbeth. They will come and take you. Don’t you understand? It’s not safe.

Pieter reached out his hand and touched her face.

— You can’t worry, not here.

And the worry fell away.

THEN MANY THINGS BETWEEN THEM WERE SAID.

Yes, in the day then there was the sitting in the house, the drinking of tea. There was the telling of stories, Elsbeth telling of her life, Pieter telling of his. There was the rising up, the out-of-doors, a walking in the woods.

— I was weaving, said Elsbeth, one day, a bolt of cloth, and there was no red in the thread, none at all, yet again and again, a red shape grew on the loom, small, here and there.

— I dreamt once, said Elsbeth, of a sea at the bottom of which our country lies. Those who live above take boats upon the sea and wonder at its depth, a depth so inconceivable that they dare not attempt it. They have myths and stories about the sea floor, but they know nothing of it. And here we think ourselves upon the highest plane, yet we stand only between things. There are seas here beyond the plains, and lands in the depths of those seas, just as we may look up through the slanting light and see the passing of ships in the heights of the sky.

— Have you, asked Pieter, seen this passing of ships?

— I have not, said Elsbeth.

— I have killed men, you know. Other than the two for which I fled. I have made the woods my own, and when others come there, I have come upon them and taken them, as I choose. I take animals in the woods, and I use their flesh for my table, their skins for clothing. I use their teeth for tools, their bones to build fences. When I have killed, I make a pile of stones, a cairn, and I set in my memory who it was, what it was that died there and how. My mind is shaped like a map of these cairns. My geography is the laying out of a great flatness peopled with cairns. One a bird, one a farmer, one a girl, one a deer. There are hundred, hundreds in the woods, for I have gone far and with great weight in my hands.

— There have been, said Elsbeth, some lost from the village, and no one knowing why.

But she did not feel any fear.

— Are you not afraid of me? asked Pieter.

— I am not afraid, said Elsbeth, not of you.

— Whether there is a name put to a place or not, still a place has a name, said Elsbeth. What do you call this place, or if you call it nothing, what does it call itself?

— I began, said Pieter, by walking around it twice. I began by discovering a place for a hidden field, a kind situation for animals. I began with winter here, and then spring, then summer, then fall, then winter again.

But I did not think to name it until my house had stood full ten years with no visitor.

Elsbeth smiled.

— That is a fine name, she said, House-Without-Visitors. But now there is a visitor.

— You are not a visitor, said Pieter. Nothing that’s mine is made without acquaintance of you.

Then they stood by the stream at the foot of the hill, where the roots of Lochen trees ran like a bridge here and there over it, and Pieter had made a bed for fish catching with the hands.

There was silver moss there.

Beneath a tree some distance into the forest, she could see a pile of stones.

— Who was it, she asked, died there?

A hare, said Pieter, the father of hares, the son of hares, an old hare, far gone through life. I caught him with a string trap and killed him with a knife.

— If I were to go first into a house of stone, and then into a house of wood, and then into a house of straw, and then into a bare roof set upon poles, and then to lie upon the empty ground beneath the sky with a blanket, and then even to cast the blanket aside and lie in the cold on the open ground, would you not think that I was making a grave for myself? For I can tell you that I have descended into what I am by throwing away the false edges of what I have been told. As I passed from house to house, the stone walls stayed with me, the wood supports, the pounded clay ground, the blankets, yet I threw them away. Everything you dismiss that is of use stays in the language of your hands. But I have seen your weaving, and I know you know the language of hands.

Elsbeth smiled and opened her hands looking down over them. They were thin hands with long fingers.

She thought of the darting shuttle that was so fine to hold, and of her shop as it stood now, empty in the town. There would have been no one to unlock it in the morning. Her workers would have come and gone. Someone would have called at her house, and found her absent. Catha would be wondering, where might she have gone. And there would be no answer. In the town there was no other place to have gone, nowhere verging into infinity, no place where one could not be found. Would eyes turn westward, to the wood, to the low road? They would not. No one thought of going on the low road. Only Catha might think she had done it, and she would tell no one.

— How is it that you live? asked Elsbeth. By hunting?

— I keep animals, and a field. I hunt in the long days, and sometimes at night. What you must understand is that when a person lives alone and sees no one, time is not like it is for others. There is so much time, so much time in the day I can’t tell you. I have lived whole seasons in a single afternoon. What can be done in a day can be years and years of work, and in thinking, the end can truly never come. I have sat staring in a pool of water for weeks, and risen, half dead, but thinking only longer on the thought I found in the depths. I have dreamt at night of lives unlived in which I lived, in which I was born and lived full fifty years, sixty years, seventy years before dying and waking back into this life. What wisdom comes from such experience? What light trails back through these thrown-open windows? I become more and more as the objects of my alone-ness grow into extensions of my living.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.