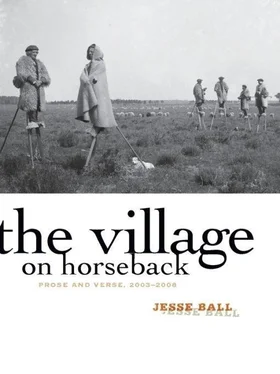

Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Milkweed Editions, Жанр: Современная проза, Поэзия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

- Автор:

- Издательство:Milkweed Editions

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness

The Way Through Doors,

New Yorker’s

The Village on Horseback

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Falk, the present mayor’s brother. The present mayor’s name was Galvin Falk and he hated no one so much as Pieter Emily.

Did we say there was no search on that day twenty-five years ago? Say then there was rather a hunt. Galvin Falk led some dozen men through the woods again and again, scouring the underbrush for some trail of blood or scent. Dogs were called, nets laid across saddles. Down they went, all down to the low road, where they stopped, gathering their horses’ necks close.

— If he’s gone further, then he’s damned.

And they rode back.

Firsk was not known to many, for the towns that had its trade were jealous of this trade, and would not share it. The truth is, the prices they paid Firsk’s traders were nothing to the prices their traders received from farther traders. This was the same as one went from town to town, farther and farther, with each place valuing the cloth, yet knowing still less about it.

Each spring, the traders of Firsk would reach the towns just beyond the mountain passes. They would come with many mules, laden down. They would set up a broad bazaar and sit cross-legged, smoking long pipes and muttering strange rhymes.

Much ill was said of these men. Jaim, for instance, knew they were disliked by those in the world. But they were honored too, for was it not their trade that meant the most?

Yet now the world had been dispelled by the drought.

||

She dressed and wrapped a coat around her and, taking up a stick, went out into the night. First along the planked street, and then off into its ending, and down a stair to the fields beyond. The road was there, a slight ways off. There was hardly a moon, and the darkness was thick, but growing thinner. She stumbled to the road and set out in truth.

The mountains rose, etched as a matter of edges on the dim sky. The trees appeared in strength as she reached the edges of the farmland, the grazing meadows, and came in truth to where the town ended.

On she walked, stumbling sometimes in the muddling dark, off through the trees where the road lay. I am on the low road, she told herself, and a panic rose that fell away only when she recalled herself to what it was she had to do.

I must tell him.

And a light came then behind her eyes as she saw once again the landscape of days gone. They were digging a tunnel, she and Pieter, beginning in the hidden center of a bush, and passing away down into the cellar of Pieter’s father’s house.

Pieter was standing by the bush and calling to her. She held a spade in her hand.

— Elsbeth, he said. Come now, there’s little time.

Elsbeth shook her head. The sun was rising. Had she been asleep? The sun was rising, setting the dark aside in the eastern reaches of the sky. She thought she saw movement in the trees. Was it a man? First behind one tree, then out from behind a farther tree. She was sure of it.

Fifteen miles. Fifteen miles she’d walked and now the sun was rising. She was out beyond where anyone had business going, out beyond where anyone had gone.

The road rose. She looked over her shoulder, but could see no more motion in the woods. Just the rattling of birds, the stirring of insects.

The road rose and fell away down down down a long slope. The trees seemed to overtake the road on both sides, and the wood grew thicker and thicker as her eye passed farther into the distance. Yet there the road was again, and again, winking at turns.

And there, away on the right, a hill, and on the hill, a house.

— Pieter Emily, she said. And she set off again.

The house was simply built but strong, thick wooden beams all around, and a thatched roof of the old sort.

There were many narrow windows all around, and a door set in the ground that must lead to a cellar.

On the step at the front, a man was sitting.

— Elsbeth, he said. You’ve come.

How he could have passed so many years without changing, she couldn’t say, but it was true. She knew him immediately and completely. His eyes were narrow and gray. His face was thin and young. His hair fell wild from his head. He wore a simple coat, simple trousers and boots. He was not tall, he’d never been tall. He looked young at first, but there was something old too, something old and far that rose in him when he came to his feet.

— Pieter, she said. They are going to come for you.

He shrugged and looked away west.

— Will you come in?

Then up the steps and through the open door.

Shall I describe the fineness of Pieter’s little house? The walls were thick, with beds and cupboards, shelves and chairs, even a table all inset. The narrow windows drove the light like lace here and there patterned on each opposite wall, so that the house was strung through with a mist of sun.

Pieter lit the stove at the room’s center, and set water to boil.

— Sit now, he said. For it is no short way you’ve come.

— There’s been a meeting. They will come here, I don’t know when. They know you’re here now.

Her voice was full of concern.

— It is kind, he said, for you to worry, but let us speak of it no more.

And he set before her a basket of flat cornbread.

— We are old friends, he said, come together again. Let us speak of gladder things.

Elsbeth rose and crossed the room. Here and there were hung tools and devices. A long axe, a lantern, a drawknife, a pair of gloves that would cover the arm up to the shoulder.

And set upon a shelf, the green book.

She took it up. The cover was thick, the book was like a flat tablet, for it enclosed only three leafs within.

Pieter poured the water into a tea-pot, and brought out two thin porcelain cups.

— Where did you get all these things? You did not return to the town.

— Where did I get all these things? asked Pieter, lifting a saucer. It has been a very long time I have lived here alone, with no use for porcelain.

His eyes looked out as if through the wall.

— I will tell you a story, he said. A dog passes along the street. It sees a child. The child turns and looks in through a window, seeing a woman. The woman cuts herself with the sharp arm of a scissor, and cursing the scissor, sees her husband on a ladder at the far window, sees him and watches as a wind rises suddenly, inexplicably, and casts him off the ladder down into the street where the first person to reach him finds him dead.

Elsbeth narrowed her eyes.

— What do you mean?

— I will tell you a story, he said. A bird circles in the air, and sees with its length of sight a child crossing a stream, hopping from stone to stone. Someone is calling to the child, calling it back, but it reaches the far side, a field of tall grass. In a moment the grass is turned and grows into the shapes of some procession, a vast procession of dancing shapes that overtake the child and carries it away deeper and deeper into the field, until the procession vanishes and the grass is as it was, grass, standing grass, and the child is gone.

— I have been so long here, he said. With no one to speak to.

Elsbeth poured the tea, and tasted the cornbread. She finished the first and took another. Pieter smiled.

— What is that? Elsbeth asked.

For set in one wall there was a tiny bed, three feet long and two feet wide. It was made up with a quilt and a pillow, and even a small doll of rope and feathers lay on one side.

— There was a little boy, said Pieter, and he was born in the town. I came one day, keeping to the sides of things so no one could see me. I felt that if I brought the boy away with me, I could raise him as well as anyone. This was ten years ago.

— Cameron’s child? exclaimed Elsbeth. Mora Cameron’s child?

— I took him, I crept in the house and took him and carried him away. He was just born then, and I raised him myself. I took him everywhere with me through the wood, and carried him on my back. I taught him the songs of the morning, the long tales of night. I raised him as well as anyone could, as well as anyone. And he slept here, in the wall opposite my bed, where I could look in the night and see that all was well.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.