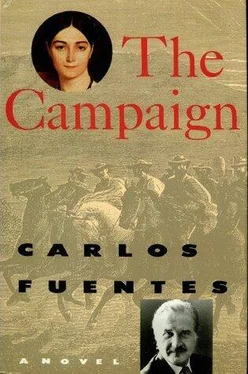

Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Campaign

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Campaign: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Campaign»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Campaign — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Campaign», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

His fame preceded him, but no one recognized him. He threw the last sign of his legendary identity — his round glasses with the silver frames — into the sea as he left the mouth of the Guayas River, where he heard his first satiric Andean song, a zamba that had come all the way from Lake Titicaca to Mount Chimborazo, if not dragged along by a dying condor, then hissed out by an irate llama.

This was his fate: people idolized him and wanted him to triumph both in war and in love. Even the blacks, who were kept away from the gangplank of the schooner in Maracaibo by shouts of “Evil race!” bawled out by exasperated royalist officers — even they peered out from among the sacks of cacao, whiter and certainly less damned than they. These blacks, despised by the Spaniards and the Creoles, were the defeated troops of another revolt, “the insurrection of the other species,” which very soon recognized the reality of the wars of independence: everyone wanted freedom for themselves, but no one wanted equality for the blacks, who unleashed their rage against every white man in Venezuela — Spaniard, creole, Simón Bolivar himself (who condemned the black explosion at Guatire as the work of an inhuman and atrocious people who fed on the blood and property of the patriots). Baltasar Bustos now saw the embers of rage in their yellow eyes and sweaty bodies, which the Spaniards kept back, so his baggage and that of the Irish sailors with whom he blended could be unloaded. He walked on ground that seemed to him unstable, under a sky he saw suspended, all of it, like certain clouds we stare at for a long time in the calmest summers, hoping they’ll move so that we can, too: how can we move if the world has stopped dead in its tracks?

The revolution was winning in the south under San Martín; in the north, Bolívar’s early victories had been wiped out by the Spanish reconquest led by the ferocious General Morillo. The revolution in the north was sustained only by the tenacity of Simón Bolívar, exiled first in Jamaica and now back in his southern base at Angostura, his redoubt and refuge after his defeat by Morillo in the battle of the Semen, which took place almost at the same time San Martín was winning the battle of Chacabuco, with Bustos at his side. Those battles were followed by the defeat of the great rebel plainsman Páez in the battle of Cojedes. Semen and Cojedes, two battles that bottled up the patriots south of the Orinoco, and two comic words — the first for obvious reasons, the second because it recalled a euphemistic creole verb for “fornication”—which were savored by Baltasar Bustos as a good omen about his amatory fortunes in this Venezuela which Ofelia Salamanca had already reached, ahead of him as always and wildly enthusiastic about the implacable royalist brutality of Morillo.

“She passed through Guayaquil, heading for Buenaventura.”

“She disembarked in Panama, crossed the Isthmus.”

“She took ship in Cartagena for Maracaibo. The Spaniards are strong there, so she can toast their victories, the bitch.”

An ailing port of brothels and shops, the latter empty because Maracaibo was under constant siege by the rebel forces, the former overflowing with all the refuse tossed up by a war which had been going on for eight years, during which time the armies of the king fought the patriots over harvests and cattle, while slaves fled burned-out haciendas and masters doggedly clung to slavery with or without independence. The peasants had no land, the townspeople had no towns to return to, the artisans had no work, the widows and orphans flooded into the royalist port out of which chocolate, in ever diminishing quantities, was exported. As always, our bitter supper sent out all of its desserts to the world.

Baltasar Bustos tossed his glasses into the Guayas River. They hadn’t helped him find Ofelia Salamanca. Now, with no guide but his passion, he would traverse plains and mountains, rivers and forests until he wore out the legend and made it into reality. For an entire year, while Bolívar conquered New Granada and royalist power spent itself because it had to be constantly on guard, Venezuela lived in suspense, waiting for the decisive battle between the Liberator and the royalists, between Páez and his lancers and Morillo and his Spanish regulars. But in Maracaibo’s brothels, bars, hospitals, docks, and warehouses — and no longer in the salons, as he had in Lima and Santiago — Baltasar Bustos sought out news of his beloved that would justify, when the two met, the songs that were being sung right there — and not at nonexistent creole balls — by whores, mule drivers, children, stevedores, and nuns from the first-aid station: the ballad of Baltasar and Ofelia.

Did she know them? Did she know those lyrics, some funny, some silly, most dirty? Was she what the songs said: an Amazon with one breast cut off, the better to use her bow and arrow, who came from a country exclusively of women, who left it once a year to become pregnant and who killed all male children? The way those ballads described him was also not true. Obsessed, he walked every street and alley in the tropical port, hoping to glean accurate information and hearing only inaccurate songs, wearing himself out in the unrelenting humidity, eating bad food, in perpetual danger of fever.

A pair of eyes followed him as he became a familiar though unidentifiable figure. This man was not the one from the song. But the eyes that followed him had seen him like this before, as he was now, just as he had been when he returned from the Upper Peru campaign, thin and hard. From a bay window, the eyes watched him through shutter slats and black veils. This woman had always appeared enveloped in dark cloth, but now her dresses of gloomy, mournful black were no longer reflected in the glitter of drizzly Lima nights.

She sent a sharp little black boy dressed as a harlequin to bring him to her. Thus it was that Baltasar entered the Harlequin House in Maracaibo for the first time. Fame had kept him away; the whorehouse was as famous as the legend of Ofelia and Baltasar, and he was afraid of being recognized there. Fame is shared and recognized everywhere. Bustos was right. He was recognized, but not when he came in, not by the company of the bordello nymphs, women of all colors and tastes, whom Baltasar imagined, as he strolled among these odalisques with naked bellies, as all tied to nature by their wide or deep, wrinkled or pristine navels, nearer to or farther from the separating scissors, but all those navels sighing with a life of their own, as if a whore were a whore simply to prolong the splendid idleness and the sinless sensualities, suspended in nothingness, of prenatal life. Undulating whores: lewd blacks from Puerto Cabello, lank Indians from Guayana, repentant mestizas from Arauca, cynical Creole girls from Caracas, the French from Martinique with their fans, a Chinese with a breast between her legs, bovine Dutch from Curaçao, distracted English tarts from Barbados who pretended not to be there at all. Baltasar Bustos, led by the black harlequin, smelled their mustard and urine, incense and skunk, congereel and sandalwood, guava and Campeche wood, tea and wet sand, sheep; all these humors gathered in the grand salon decorated in the style of Napoleon I, with ottomans, plaster sphinxes, fixed lights, and stopped clocks, the grand salon of the most famous brothel in a port famous for piracy, plunder, and slavery, now besieged by the patriots of an empire, Spain’s, that believed itself installed there for all eternity.

The harlequin and Baltasar finally reached their destination, and Baltasar stood as if before a conquered queen, conquered by herself. The greedy eyes of the prostitutes followed him until the doors closed behind him. The woman in black lost no time: she said she’d been expecting him to turn up, even though she knew that he did not want to find within the brothel what he was looking for outside. He was involved in other things — she was told everything — because out there he could not expect to find this Ofelia Salamanca. But here he did, correct? No, he shook his head, not here, either; I’ve almost lost all hope of ever finding her. At this stage in the game, Baltasar, would you prefer never to find her, to go on searching forever because that justifies your life, this rhythm that makes you crazy and makes all of us women crazy when we sing and dance it? Not even a Chinese girl with three breasts? Our dearest?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Campaign»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Campaign» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Campaign» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.