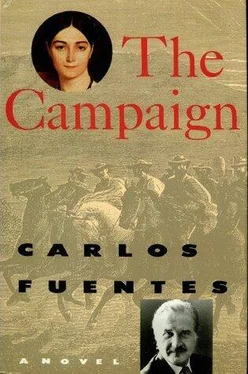

Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Campaign

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Campaign: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Campaign»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Campaign — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Campaign», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“With my friends, I could have founded a world,” said Baltasar Bustos, his head bent low.

“And without them…” San Martín began.

“I can only live out a passion.”

The general did not understand what the young fellow was saying. He rested his hand on Baltasar’s shoulder and said, “They were heroes.” Then he promoted Baltasar to captain on the spot.

Baltasar stayed behind, alone, with the bodies of Francisco Arias and Juan Echagüe. Were they really heroes? Was José de San Martín himself a hero, the closest thing to a living hero Baltasar would ever know? In the funereal gloom of the cathedral, unbroken even by the baroque glitter scattered there by its architects, who besides being Jesuits were Bavarians, Baltasar saw in his mind’s eye the Liberator, his friends, Miguel Lanza and the Indian Baltasar Cárdenas, Father Ildefonso de las Muñecas, all the warriors he’d met: he saw them without cavalry, without a battlefield, without infantry. Perhaps that was what José de San Martín held in his most secret soul: the vision of a world without heroes, in which men like himself, and also men like Lanza and Cárdenas, the young Father Arias and Captain Echagüe, his friends, would no longer be possible, because there would be no more saber battles, no more hand-to-hand fighting, no more code of honor, only fratricide, battles won against brothers, not against enemies; foreseeable, programmed wars in which death would be determined and accomplished at a distance. Dirty wars in which the victims would be the weak. The hero — he turned to look at the square shoulders of General José de San Martín in his dress uniform, solemnly walking toward the exit, speckled by the diffuse light of the cupolas — would then be like the god of the mountains, a dying god. Then he imagined the pathos of a San Martín grown old, firmly resolved never to stain his sword killing Argentine citizens, preaching through example, refusing to be “the vigorous arm,” no matter how annoying the bickering of the “intractable, the apathetic, and the savage.” At the apex of victory, San Martín refused to celebrate with romantic exuberance. His occasional solemnness was excused by the excessively stoic, Castilian severity of this son of Palencian parents. If he was going to avoid the temptation of dictatorship, it would not be to avoid responsibility for Argentina but to say to Argentina that everyone should behave as he did. Everyone should be responsible. From this day forward, each one of us must stand guard over his own life. Someone had to say it, and not from the abyss of the failures to come, but here and now, at the high noon of triumph, and triumphing over the passion for victory.

When he understood this, Baltasar Bustos felt a desire to run to the last hero and embrace him. But that would have been just one more celebration, a denial of the seriousness of the dying god. He wouldn’t insult him with recriminations or with praise. It was better that Baltasar remain with his comrades, hold on to this tenderness, these hopes, these jokes, this intimacy he would never again know.

The general understood and wished him a good voyage.

One sunny February morning, Baltasar boarded a schooner, the Araucana, sailing from Valparaíso to Panama. It passed Lord Cochrane’s flotilla, preparing for the attack on Lima. As he sailed by, Baltasar named the ships of the small fleet in a kind of farewell-to-arms: the forty-six-gun frigate Lautaro, the brig Galvarino, armed with incendiary rockets, the schooner Moctezuma, the man-of-war San Martín, and the transport ships and attack launches.

In Santiago he’d been told: “The woman you seek is in Caracas. But don’t expect anything good from her.”

For him, the war was over; only passion remained.

But in Santiago he did not want to look for Gabriela Cóo.

7. Harlequin House

[1]

Traveling with the Irish sailors between Callao and Panama, Baltasar Bustos recovered the slim figure he had during his days in Upper Peru; with only a Panama hat (bought in Guayaquil) for cover, he insisted on crossing the emerald forest between the two seas, between Pedro Miguel and Portobelo. The Indians of San Blas, whose faces marked with blue scars were a wounded parallel to the immutable colossi of Barriles, guided him among clay statues in the shape of men standing on each other’s shoulders. The waters of the Panamanian lagoons reflected nothing, so intense was the sun that blinded the men during the day. And at night he could make out the lights of Portobelo, where a second schooner, on the other side of the isthmus, waited to take him to Maracaibo, the ancient fortress of the Spanish Main, besieged from time to time by the arms and later by the fame of Drake and Cavendish. But now, in more recent memory, Maracaibo’s renown was associated with the pirate Laurent de Graff, who never attacked the Venezuelan harbor unless accompanied by a private orchestra of violinists and drummers; and the French captain Montauban, who would appear on its briny streets only in a sedan chair carried by stevedores and preceded, even at midday, by a procession of torchbearers.

The fame of the ancient English, French, and Dutch pirates was nothing compared with that which ran before our hero, Baltasar Bustos, in his celebrated search for Ofelia Salamanca throughout the American continent. The trails of the alpaca and the mule were slow, the jungles thick, the mountain ranges arid and impassable, the seas of the buccaneers bloody, and the ravines deep, but news traveled faster than any Indian messenger or Irish schooner: a fellow of unimpressive aspect, plump, long-haired, myopic, has been in pursuit of the beautiful Chilean Ofelia Salamanca, from the estuary of the Plata to the gulf of Maracaibo. They say he’s never seen her, much less touched her, but his passion compensates for everything and, despite his physical weakness, stirs him to fight, saber in hand, for the independence of America, side by side with the fearsome guerrillas of Miguel Lanza in the mud of the Inquisivi, with the legendary Father Ildefonso de las Muñecas at the head of the Indian hordes of the Ayopaya, with José de San Martín himself in the heroic crossing of the Andes.

Some hero! Baltasar Bustos said to himself when in the fetid port of Buenaventura he heard the first song about his love, transformed into a cumbia and danced, amid long, black plantains that resembled the phalluses of extinct giants, by immense black women, their heads decked out in red-checked handkerchiefs tied in fours. The multiple skirts the women wore did not impede them from communicating exactly what was there below or from moving their hips rhythmically, regularly, delightfully, and slowly. Some hero! Baltasar repeated to himself in Panama, listening to the story of his frustrated romance transformed into a tamborito and danced by Creole girls as white as cream, wrapped in immense skirts that turned their bodies, like those of milky spiders, into fans. Some hero — who had to struggle to resist the temptation of shortbread and powder cakes that dissolve on your lips, prickly pears, and caramelized custard apples in those dancing ports between a scorching Pacific, free of the frozen waters of Baron von Humboldt’s current, and a lulling Caribbean, separated only by Panama’s pinched waist, the sash worn by the dancing and singing black girls: Here comes Baltasar Bustos, looking for Ofelia Salamanca, from the pampa to the lowlands! Some hero! Who would recognize him, not plump as the song had him, but once again thin, his stomach muscles hardened by days before the mast with the Irish sailors, who made their hours of work into a happy game and their hours of drunkenness and rest (which were one and the same) into nostalgic sobbing: Baltasar Bustos, chestnut-hued, his hair honey-colored, his beard and mustache blond — reborn, resembling the prickly pear he resisted the temptation to eat, his thighs taut, his bare legs covered with golden down, his chest hairless and damp with sweat, and the long hair in his armpits intimating the most salacious secrets. This was not the Baltasar of the cumbia or the tamborito —or, for that matter, of the merengue (here his mouth watered because he automatically thought of meringue).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Campaign»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Campaign» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Campaign» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.