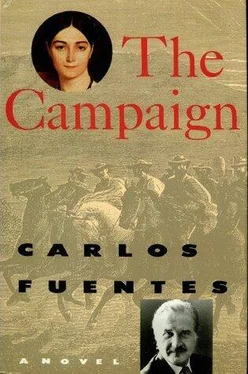

Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Campaign

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Campaign: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Campaign»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Campaign — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Campaign», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He later wrote to his friends that perhaps it was his fate to return to his father’s estate too late for some things, too soon for others. He was untimely. But they themselves had pointed out the opportunity to him. Ofelia Salamanca had left Chile and was now in Peru. There were, then, immediate and sensual reasons for being.

“Your friends sent you a note. They could not find the child. The woman’s in Lima. That’s that. Will you go?”

Baltasar said yes.

“Won’t you take me with you?”

“No. I’m sorry.”

“You’re not, but it doesn’t matter. You won’t take me because you respect me. I expected nothing less of your love for me. You would never dishonor me. We’ll leave that to the gauchos.”

“Excuse me if I am distracted. I’ve always wanted to be open to what others think and want.”

“You know I have nothing left to do here. I have no one to care for.”

“There’s the house. The gauchos. You just said it yourself.”

“Am I the mistress?”

“If that’s what you want, Sabina.”

“I’m going to die of loneliness if I don’t give myself to them.”

“Do it. Now let’s bury our father.”

5. The City of the Kings

[1]

The drizzle falling on Lima during that summer of 1815 stopped when the Marquis de Cabra, venturing out onto his baroque balcony suspended over the small plaza of the Mercederian Nuns, said, to no one in particular — to the fractured cloud, to the invisible rain that chilled one’s soul: “This city enervates us Spaniards. It depresses and demoralizes us. The good thing is that it has the same effect on the Peruvians.”

He cackled like a hen over his own wit and closed the complicated lattices of the viceregal windows. His Indian valet had already helped him into his silver-trimmed dress coat, his starched linen shirt, his short silk trousers, his white stockings, and his black shoes with silver buckles. All he needed was his ivory-handled malacca stick.

“Cholito!” he said to his servant with imperious tenderness. He was just about to give the order, but the Indian boy already had the walking stick ready and handed it to his master, not as he should have — so the marquis could take it by the handle — but offering the middle of the stick, as if handing over a vanquished sword. This cholito, this little half-breed, must have seen quite a few defeated swords handed to the winners of duels over the course of his short life. They were part of the legend of Peru: every victory was negated by two defeats, so the arithmetic of failure was inevitable. Now what attracted the Marquis de Cabra’s attention was something familiar: the ivory handle of his stick was a Medusa with a fixed, terrifying gaze and hard breasts that seemed to herald the stones set in the eyes.

It was a present from his wife, Ofelia Salamanca, and from being handled so much, the Medusa’s facial features had lost some of their sharpness. For the same reason, the atrocious mythological figure had completely lost her ancient nipples. The marquis shook his head, and his recently powdered wig dropped a few snowflakes on the shoulders of the former President of the Royal Council of Chile. The brocade absorbed them, just as it absorbed the dandruff that fell from the thinning hair of the sixty-year-old man who this afternoon was walking out into a Lima divided, as always, by public and private rumors.

The rumors concerned the situation created by Waterloo and the exile of Bonaparte to Saint Helena. Ferdinand VII had been restored to his throne in Spain, and refused to swear allegiance to the liberal constitution of Cádiz which had made his restoration possible. The Inquisition had been reinstated, and the Spanish liberals were the object of a persecution that to some seemed incompatible with the liberals’ defense of the homeland against the French invaders, during which time the idiot king lived in gilded exile in Bayonne. The important thing for Spain’s American colonies was that, once and for all, the famous “Fernandine mask” had fallen. Now it was simply a matter of being either in favor of the restored Bourbon monarchy or against it. It was no longer possible to hedge. Spaniards against Spanish Americans. Simón Bolívar had done everyone the favor of giving a name to the conflict: a fight to the death.

The Marquis de Cabra preferred to prolong, just as he was doing at that very moment, to the rhythm of the coach, the public rumors in order to put off the private ones. During this enervating summer of unrealized rains — like a marriage left unconsummated night after night — he himself was the preferred object of Lima gossip. His entrance into the gardens of Viceroy Abascal, in this city where gardens proliferated as an escape from earthquakes, would, as the witty Chileans called it, keep the rumor mill churning at top speed.

The truth is that other things held the attention of the guests at the viceroy’s soiree, first a game of blindman’s buff that the young people who basked in the blessings of the Crown — the jeunesse dorée, as the Marquis de Cabra, always aware of the latest Paris fashions, called them — were enjoying, as they dashed and stumbled their way around the eighteenth-century viceregal garden, a pale imitation of the gardens of the Spanish palace at Aranjuez, themselves the palest reflection, finally, of Lenôtre’s royal gardens.

“Goodness, with all these blindfolded figures in it, the garden looks like a courtroom,” said the marquis, as usual to no one and to everyone. That allowed him to make ironic, snide comments no one could take amiss because they weren’t directed at anyone in particular. Of course, anyone who so desired could apply them to himself.

The garden actually resembled nothing so much as beautiful, flapping laundry because the flutter of white cloth, gauze, silks, handkerchiefs, and parasols dominated the space: floating skirts, scarves, linen shirts, hoopskirts, frock coats the color of deerskin, tassels, fringes, silver braid, epaulets, and military sashes, but above all handkerchiefs, passed laughingly from one person to another, blindfolding them, handcuffing them, allowing the blindman only an instant, as white as a lightning flash, to locate his or her chosen prey. Two young priests had also joined the game, and their black habits provided the only contrast amid so much white. From his privileged distance, the marquis noted with approval the nervous blushes of the beautiful Creole youngsters, who avidly cultivated fair complexions, blond gazes, and solar tresses. That explained the parasols in the hands of the girls, who wouldn’t set them aside even when they were blindfolded. They would run charmingly, one hand holding the parasol, the other feeling for the ideal match promised by the luck of the game. On the other hand, the heat and the excitement of the game brought out dark blushes among the boys, as if the image of the pure white Creole required total inactivity.

The newly arrived spectator smiled; either in the curtained bedroom of a lattice-windowed palace or in a dungeon, that’s where these fine young gentlemen would finally take their rest; that was what the war of independence promised Lima’s beautiful young people: renewed power or jail. War to the death … For the moment, far from the insane, incredible resistance of the bands of Upper Peru’s guerrillas, far, even, from the perilous peace of Chile, Peru remained Spain’s principal bastion in South America. But for how long?

It was like playing blindman’s buff, said the roguish, amused marquis, introducing himself like some sort of minstrel into the circle of young people, striking coquettish poses, tossing away his three-cornered hat, nostalgic perhaps for the capes and broad-brimmed hats that Charles III had banned in a vain attempt to modernize the Spanish masses. As he walked, he scattered the perfume and powder of his eighteenth-century toilette among these fresh but perspiring young people, who had abandoned the classic wig in favor of long, romantic tresses that floated in the breeze … Even in Lima the generation gap began with hairstyles; it indicated — and this the Marquis de Cabra, of an understanding nature, wanted to believe — that it began in their heads. It was the era of heads. Isn’t that exactly what Philip IV’s minister had demanded? “Bring me heads!”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Campaign»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Campaign» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Campaign» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.