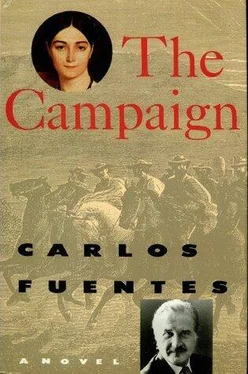

Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Campaign

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Campaign: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Campaign»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Campaign — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Campaign», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Baltasar returned to the pampa too late and too early. Too late to convince José Antonio Bustos, who had died two days before. Too early to avoid the uncertainty that would accompany him from that day on. His father was laid out with his hands folded, his fingers wrapped around a scapulary and with a candle, like a white phallus, between his fists, clenched forever in rigor mortis.

His father was so fragile and wasted that to Baltasar he seemed about to fly away. And while the candle looked like a mast, the scapulary was an anchor more powerful than any wind. Actually, his father looked more like wax. Bustos the creole recalled Miguel Lanza and his saint’s complexion. Now Bustos’s father had acquired it as well, but at the price of death.

He questioned Sabina: what did he say, what was he thinking at the end, did he die in peace, did he remember me, did he leave me any final message?

“You think you’re asking about him, but you’re only thinking of yourself,” said his sister, scowling in the way that made her ugly, making it impossible for Baltasar to see her as lovable despite her ugliness.

“You’d like to know, if you were me.”

“The Prodigal Son,” Sabina declared in staccato tones, grimacing hideously. “He said it was impossible to swim against the tide. He thought everything was a mirage, that everyone was deluded, and he was right. He died calm but uncertain, as you can see by the candle and the scapulary. He left the message for you I’ve just given you.”

She seemed to hesitate for an instant, then added: “To me he said nothing and left no message.”

“You’re lying again. He loved you and was most tender with you. You were close to him. You spoke harshly to him, and he allowed it. You’re saying these things to make me feel sorry for you and guilty about myself. Didn’t someone bring a blond child to live with you here?”

Sabina shook her head. “No child, no father. And you’ve come back. You can no longer ask me to stay on here.”

“Do as you please, sister.”

The filial word turned bitter on his lips. He had just left so many brothers, dead, alive, or on the point of perishing; there were others he missed, Dorrego and me, Varela, whom he had not embraced for five years. And Sabina could only look at him in wonder, as if his words were those of a man who was not (or was no longer) standing before her. She spoke to her memory of Baltasar.

“You’ve changed. You’re not the same.”

“How so?”

“You’re like them,” she said, looking out toward the gauchos gathered in mourning around the house. They, too, were staring, with a wonder even more secret than Sabina’s, at the prodigal son who returned looking like them, Don José Antonio’s peons, once nomadic and now firmly rooted in place by the laws of the Buenos Aires revolution. It shouldn’t be this way, said the eyes that followed him around the shops and stables; the son of the master shouldn’t look like the master’s peons, his mule skinners, his experts in tossing the bolas, his riders, his horse breakers, his cowpunchers, his blacksmiths, his bellows operators. He should always be the little gentleman; he should always be different from them. How many of José Antonio’s bastards were there among the gauchos? One or a thousand: now Baltasar looked like all of them, no longer like himself.

Ever since Simón Rodríguez had raised him from the bed of Acla cuna and showed him his reflection in a windowpane in Ayopaya, Baltasar hadn’t wanted to look at himself in mirrors. Usually, the guerrillas didn’t carry them; he hoped nature would sculpt his features, using life’s blows. The mountain, after all, did not look at itself in the mirror, nor did those overflowing rivers in the jungle. The condor never thought about itself; why should Baltasar? Only now, parted from the band of guerrillas, back home and concerned with a death in the family, and under the gaze of his old servants, did he feel the temptation to look at himself in the mirror. Again, he resisted that temptation. The looks the gauchos gave him were enough: he’d turned into them. He touched his long hair, his unshaven beard, his skin tanned to leather by the sun, and his lean cheeks. Only his metal-rimmed glasses betrayed the Baltasar of before. How could his eyes change? His old antagonisms about inequality could still creep in through those eyes. He looked like them, he wanted to prove it by strolling through the ranch as he did out in the wild, showing his recently acquired familiarity with nitrates and iron, with the products of cattle ranching — jerked beef, tallow, bristles, bones.

But he was different from the gauchos. Not one of those men felt, as Baltasar did on returning to his house, that he was still trapped by the land of the Indians, the royalist army, the separatist petty republics, and the enlightened hegemony of Buenos Aires. Not one of these gauchos shared this political and moral anguish; for them, these divisions did not exist. All they knew was the immediate division between mine and yours: if you give me enough of yours, I’ll be satisfied with mine. During his ill-fated campaign in Upper Peru, didn’t Castelli say that the people should make their own decisions, exercise self-control, develop their economic, political, and cultural potential, and think whatever they chose? Baltasar Bustos looked one last time at his father’s crossed hands, entwined in the scapulary, stained by the candle, insensible to the scorching pain, and then looked at the puzzled faces of the gauchos, who hadn’t expected the return of a master equal to them. It was then he remembered how infinitely far away the Indian world was, how infinitely far away the fantasy his reason fought against, and how close his namesake, the Indian leader. None of them thought as they wished. They all thought as they believed.

The idea devastated him; he lost all heart, and finally understood why Miguel Lanza laughed, the only time that rueful saint, that sleepless warrior, ever laughed, when he repeated the words of the emissary from the Buenos Aires revolution in Upper Peru: “In one day, we shall do the work of eternity!”

They were risible words. Was the burden Baltasar Bustos felt on his shoulders as he said that in his father’s frozen ear also risible? “It’s up to me to do, over the course of my entire life, the work of one day. The entire responsibility for the revolution for independence weighs on me and on each one of us.”

The candle finally melted in the unfeeling hands of his dead father. The scapulary, however, remained, coiled like a sacred serpent. What would change, who would change it, how long would it take to change things? But was it worth it to change? All this came from so far off. He hadn’t realized before, their origin was so remote, that the American cosmogonies preceded all of secular reasoning’s feeble speculations; écraser l’infâme was in itself an infamy that called for its own destruction: it was a weak, rationalistic bulwark against the ancient tide of cycles governed by forces which were here before us and which will survive us … In El Dorado, he had seen the eyes of light that contemplated the origin of time and celebrated the birth of mankind. They did not remember the past; they were there always, without losing, because of it, either their immediate present or their most remote beginnings … How was it possible to stand next to them without losing our humanity but augmenting it thanks to everything we’ve been? Can we be at the same time all we have been and all we want to be?

His father did not answer his questions. But Baltasar was sure he was listening. Sabina had let the candle burn down. She shrieked when the flame touched the flesh. He can’t feel, said Baltasar. But she did feel: she felt the knives she wore, like scapularies, between her breasts, over her sex, between her thighs. He didn’t have to see them to know they were there; he could smell them, near his sister and his father’s cadaver, he could feel them piercing his own body with the same conviction his own fighting dagger had entered the Indian’s body in the Vallegrande skirmish. In the same way he knew “I killed my racial enemy in battle,” he also knew “My sister wears secret, warm, magical knives near her private parts”; just as he’d earlier found out “Miguel Lanza does not want me ever to escape from his troops, so that I can be his younger brother and not his dead brother.” Having taken all this into himself, he now wanted to distance himself from it so that he could go forward to his own passion, the woman named Ofelia Salamanca.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Campaign»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Campaign» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Campaign» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.