Otik was slipping something small and fragile into one of the bird heads.

Lars shook his head. “Otik, let’s not do this right now.”

But Otik would not be deterred. He connected a set of wires and then snapped the head of the bird onto the body. He then repeated this preparation on a second bird. His hands were working quickly, massaging the necks of the creatures with an unexpected tenderness. Back at his workbench, he opened a laptop and began to peck away at the keys, muttering to himself.

“Otik, please,” said Lars. “Let’s leave it.”

Otik slapped a final button and raised his arms in triumph.

“Let’s dance, baby,” he said, turning to face the birds.

They waited, Radar holding his breath. Shostakovich played on in the background. Nothing happened. Radar glanced over at Otik, whose face had turned sour. They waited some more. The birds lay still on the table.

“Bem ti sto majki!” said Otik, deflating back into his seat. “I told you it was problem. I told you before: amplitude shackles are such bullshit .”

“And welcome to life at Xanadu,” said Lars. “We spend most of our time attempting to figure out how we just screwed up. It’s a game of outrunning our own failure.”

“Kirkenesferda,” said Radar, stumbling over the strange word. “Wait. Are these the same people who electrocuted me?”

Lars sighed. “First of all, I want you to know I had nothing to do with your electro-enveloping. I was only ten years old at the time, so I plead the ignorance of youth.”

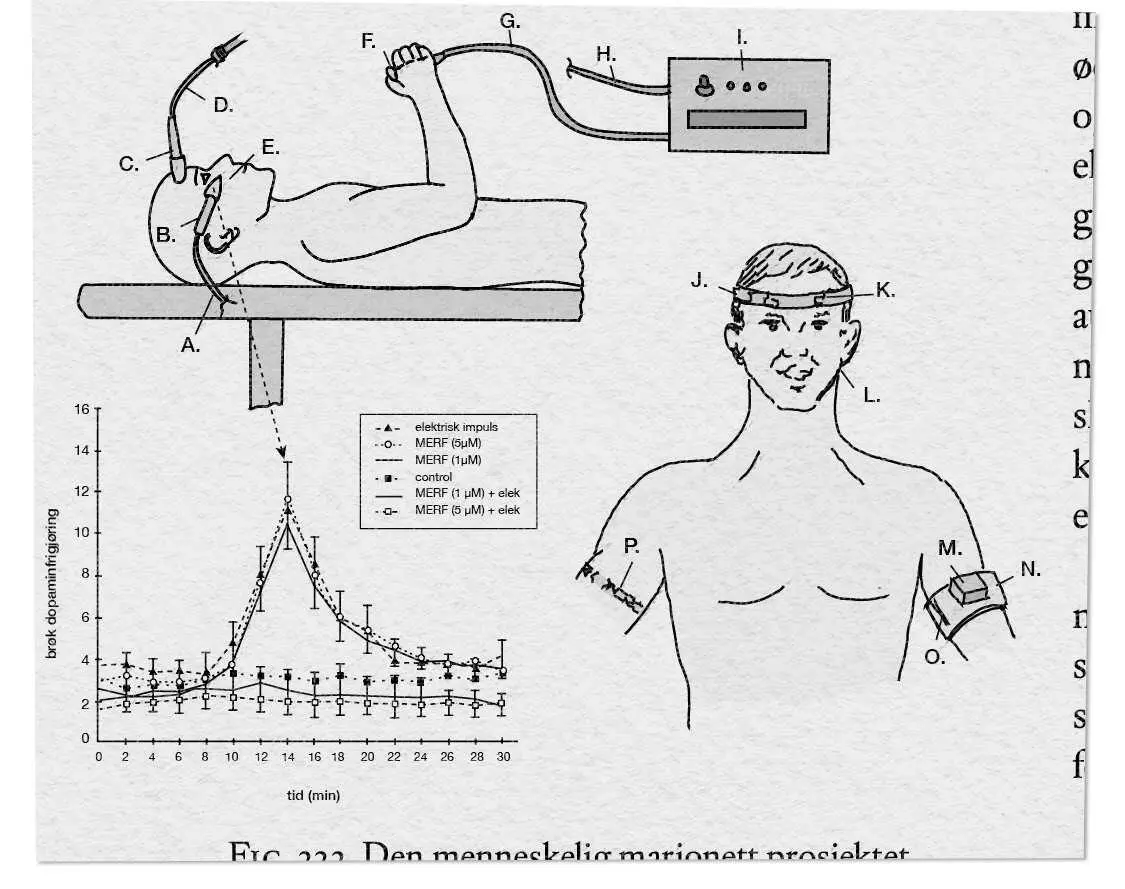

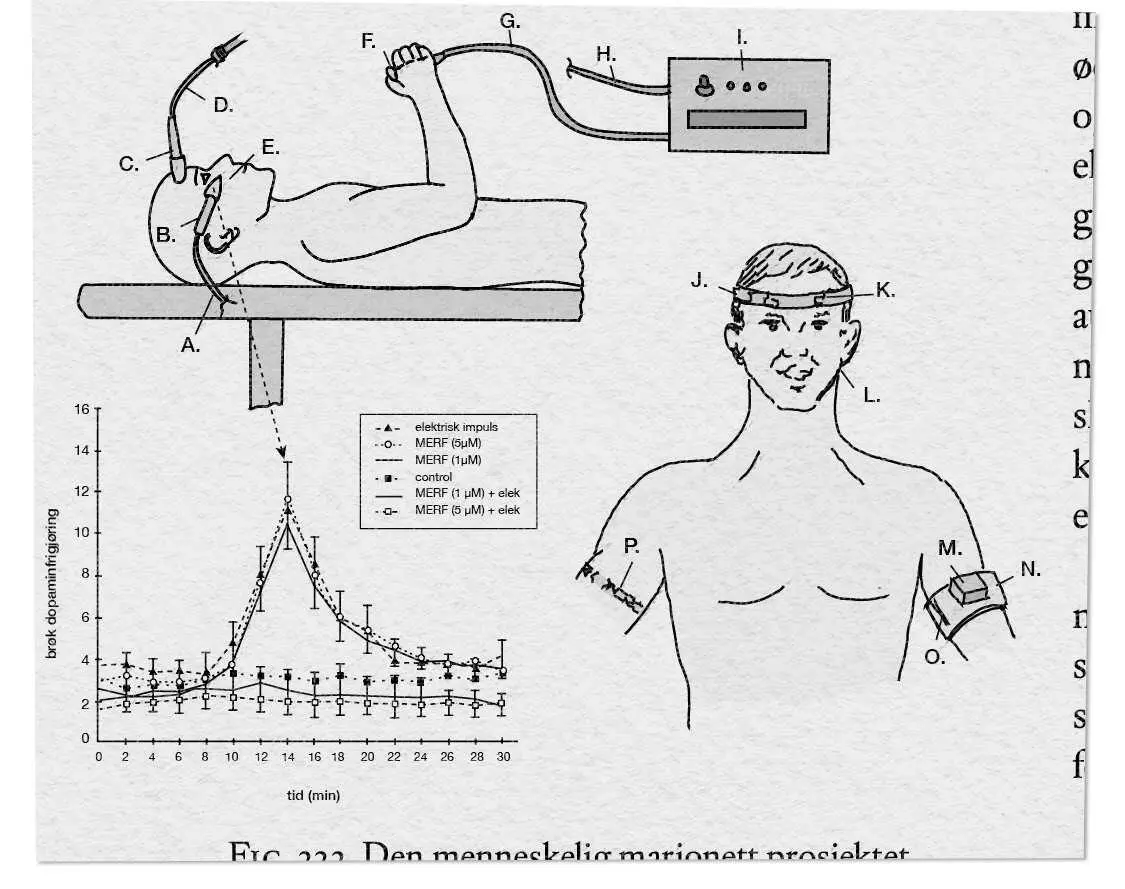

Fig. 3.9. Notes from Den Menneskelig Marionett Prosjektet

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 493

“Electro- enveloping ?” Radar said.

“The technology came about accidentally from Kirkenesferda’s investigations into some old Tesla designs. After Kirk To, they began looking into organic circuitry so as to try and make the human body into a puppet of itself. It was an attempt to circumvent Kleist’s dilemma. An awareness of ourselves as an actor on the stage inevitably corrupts the essence of our movements. We think, and therefore we cannot just be. Den Menneskelig Marionett Prosjektet was meant to rewire the body so that another could control our movements, just as if we were a puppet. The project did not pan out, but many other discoveries came from this.”

“Like how to electro-envelope someone’s skin,” said Radar.

“Well, yes. Among other things. But really, they had no idea what they were doing. The technology was primitive, brutally so. Let me tell you this: what they did to you was not right. Leif should never have offered his services. He was charismatic and excitable, but he was also a schizophrenic delusional. At the time, I worshipped him. Everyone did. And everyone wanted to believe in what he said, but now I see that he was just a boy playing with a toy, and this toy should never have been used on a living human being, and certainly not a child. I’d like to think that Kirkenesferda’s come a long way since then. We’ve matured — spiritually, morally, karmically.”

“I’m sorry,” said Radar. “I’m still not quite following you. What is Kirkenesferda?”

“It is most important group in all of performance history,” said Otik, looking up from his workbench.

“Well. . let’s stay modest, shall we?” said Lars.

“It is truth,” said Otik. “You want to argue about this?”

“What he means is that their contributions have often been overlooked.”

“It’s not what I mean,” said Otik. “I mean they are most important group in history.”

“Your father played an important role.”

“It is truth,” said Otik. “Your father, he had so much talent. He was the best.”

“He was?” said Radar. It was only after a moment that he heard the past tense in Otik’s words.

“So much,” said Otik, shaking his head. “So, so much. Genius .”

“But what do you mean, was ?”

“Ah, let’s not quibble about semantics. Otik’s English is not the best,” said Lars. Otik opened his mouth, but Lars held up a finger in warning. “I’m going to put on some coffee. Anyone for coffee? Radar?”

“I actually don’t really drink coffee,” said Radar. It was true: coffee, like alcohol, caused his already malfunctioning body to go into overdrive.

“In that case, I’ll just drink yours,” said Lars. He busied himself with an electric kettle. “So how would one describe Kirkenesferda? I think Per called us a ‘metaphysical army of Arctic puppeteers,’ but of course that’s a ridiculous explanation. Per has a tendency to overstate his case.”

“Who’s Per?” Radar asked.

“Per Røed-Larsen. My stepbrother.” Lars went over to the bookshelf and took down a mammoth beige book. He handed it to Radar. “He’s written the most comprehensive history of Kirkenesferda, even if most of it’s not quite true. He and I don’t speak anymore, but I must say his work’s impressive, if perhaps overly critical, although I would be, too, if my father abandoned me for some metaphysical army. I don’t mean to go all Freudian on you, but Per was a little obsessed. He elected himself the primary Kirkenesferda historian, much to the outrage of Brusa Tofte-Jebsen.”

Radar leafed through the book, staring at the pages and pages of graphs and tables. A whiff of the familiar. He felt as if he had held this book before.

“Your father abandoned you?”

Fig. 3.10. Jens Røed-Larsen at the Bjørnens Hule (1968)

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 96

“No. He abandoned Per and his sister. You see, in 1939, my father, Jens Røed-Larsen, was one of the most important nuclear physicists working in Norway.” Lars came over and flipped to a page in the book. “There. That’s him. Per claimed he was on track to win the Nobel Prize, but I’m not sure about all that. Anyway, when the Nazis invaded, Jens was forced to flee to Stockholm with his wife, Dagna, and their baby, Kari. Both the Germans and the Allies of course wanted him for their nuclear weapons programs, but he refused. He was something of a die-hard pacifist at the time. But while he was hunkered down in Sweden, he heard whispers about this avant-garde performance group working on the Russian frontier, in Lapland. They were supposedly making a courageous stand against the war through these art pieces centered around the physics of the nuclear bomb. You’ve got to remember that the bomb at this point was only a dream, a terrifying possibility on the horizon. Hiroshima was still two years away. My father’s interest was piqued. He heard this group were in need of a nuclear physicist on the team, so, in 1943, he essentially left his family and traveled up to Kirkenes. You can imagine what a difficult choice this was.”

“Why did he do it?”

“I still don’t know, really. War causes strange things to happen. People’s priorities shift. I suppose he came to think that this cause was something pure, something effectual. Still, I can’t imagine. It was quite a dangerous trip for my father. You see, the Nazis still controlled the entire North. The whole reason they were occupying Norway in the first place was so they could produce heavy water to make an atom bomb. But my father risked it anyway. He was guided by a small band of Sami. They say it was bitterly cold — one of the worst winters on record — and he lost two toes in the process. But he made it. They took him over the mountains and then down into Fennoscandia to the Bjørnens Hule. My father then worked on Kirk En in 1944, the first of the two nuclear events.”

Читать дальше