“So your show is about this? Quark gluton communism?”

“You’re good, Kermin. One must say this about you,” said Leif. “No, the challenge we face right now is much more mundane. You see, we’re building puppets with screens inside of them. Televisions. So they can become anyone they want. . like an infinite mask. These are certainly our most complex constructions to date. And their circuitry must be able to function in very hot and wet conditions — in the Cambodian jungle, you see, where there’s no electricity. We’re struggling to make all of this work. . The wiring is really very tricky. You work with televisions, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Little televisions?”

“Little televisions.” Kermin felt a great delight in saying this. “Very mini televisions.”

“Maybe I could pick your brain sometime about a few small matters. For instance, we are interested in liquid crystals on plasma-polymerized films. Do you know about these?”

“Of course.”

“Of course you do. You see? You and I are not so different.”

They stood, staring at the vast collection of puppet detritus. In the middle of the room sat a strange machine that looked like a suspended metal barrel resting on two trapezes, with a large collection of spiraling wires exploding from either end. The barrel was covered in bulbous glass protrusions. Kermin put his hand on one of these glass lumps. It was warm to the touch. He felt a sudden, precise absence in his chest and then his head swam, as if he had been holding his breath for too long.

“What is this?” he asked, withdrawing his hand.

“That. That’s a vircator,” said Leif. “That is what will cure your son.”

The next morning, Charlene awoke early to find Kermin already up. Radar was next to him, quietly working on an exploded radio at the little wooden table. It was chilly inside the cabin. Outside, summer snow had fallen sometime during the long, illuminated night. A fresh wet coating of white covered the ground, broken only by a lone set of paw prints that wove and wandered through the cluster of buildings.

“What’re you doing?” Charlene said sleepily, coming over to the table.

“We are repairing, aren’t we?” said Kermin.

“This radio is broken,” Radar agreed.

“I had the strangest dream last night.” She yawned. “Did you have any dreams?”

“No,” said Kermin.

“No dream,” Radar agreed.

“It must be something about being up here. Or maybe it’s just all the travel, but I swear, it was so vivid. I was on this boat or barge or something. In the jungle, floating down a big river. And I knew these people were watching me from the trees. I couldn’t quite see them, but I knew they were there. And I hear this shout, like a warning, and I expect some kind of attack, but then I look up and I see that the river is ending. Just disappearing into nothing. It’s like the water is there one minute and then it’s not there. And then, just before I get to the place where the river is ending, I wake up. And you know what’s strange? In the dream, it wasn’t that I was scared to go through that point of no return — it was that I wanted to go through, to see what was on the other side. When I woke up, I could feel this disappointment, you know?”

Kermin looked up at her. “It’s okay to give him treatment.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, we can let him treat Radar. I think it’s okay.”

“But. . but you said it was dangerous.” She shivered, hugging herself.

“He will be fine. It’s what you want. It’s what we came here for.”

Charlene studied her husband’s face. Then she sat down in a chair and pulled Radar to her.

“How’re you feeling this morning?” she asked.

“Fiiiineee,” he said, electronics in hand. “I like dat man with da white head.”

“Who’s that?”

“He means Leif. Bald-head Leif,” said Kermin.

Charlene laughed. “You do? You like Leif? Crazy old Leif?”

Radar nodded. “Yeah. He makes Kermint go explode!”

“Kermit or Kermin, honey?”

“He makes little green Kermint go explode!” Radar demonstrated with his hands, sending flecks of saliva onto the table.

Charlene smiled. She turned back to her husband, placing a hand on his leg. “Why have you changed like this?”

“It’s okay.”

“You’re doing this for me?”

Kermin nodded. “I want to fix.”

“But why now?” She was filled with a sudden wash of uncertainty. “You said you didn’t trust him.”

“I think we found something here. You said this yourself. Maybe these things happen for a reason. Maybe Leif is not so crazy as he looks. He’s giving me his promise.”

Radar reached down and plucked up a radio wire from the careful sea of parts.

“No, my little angel,” Charlene said, taking the wire from him. “That’s not for you.”

“Give it!” Radar said, reaching for the wire.

“It’s okay,” Kermin said, handing the wire back to his son. “He knows what’s for him.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she said. She closed her eyes. “I don’t know anymore.”

“It is your choice,” he said.

She nodded.

“Everything happens for a reason,” he said.

She turned to her son. “Radar, do you want to do an experiment today?”

“What’s speriment ?” he asked.

“It’s where they connect you to a big machine.”

“ Okaaaay ,” Radar said. He touched two wires together and made a fizzling sound with his lips. “Connect. Explode!” He burst his hands apart. The wires flew off the table.

“No explode, honey. Just connect,” she said.

Radar looked disappointed.

“Thank you,” she whispered to Kermin, reaching over and squeezing his hand. “I love you.”

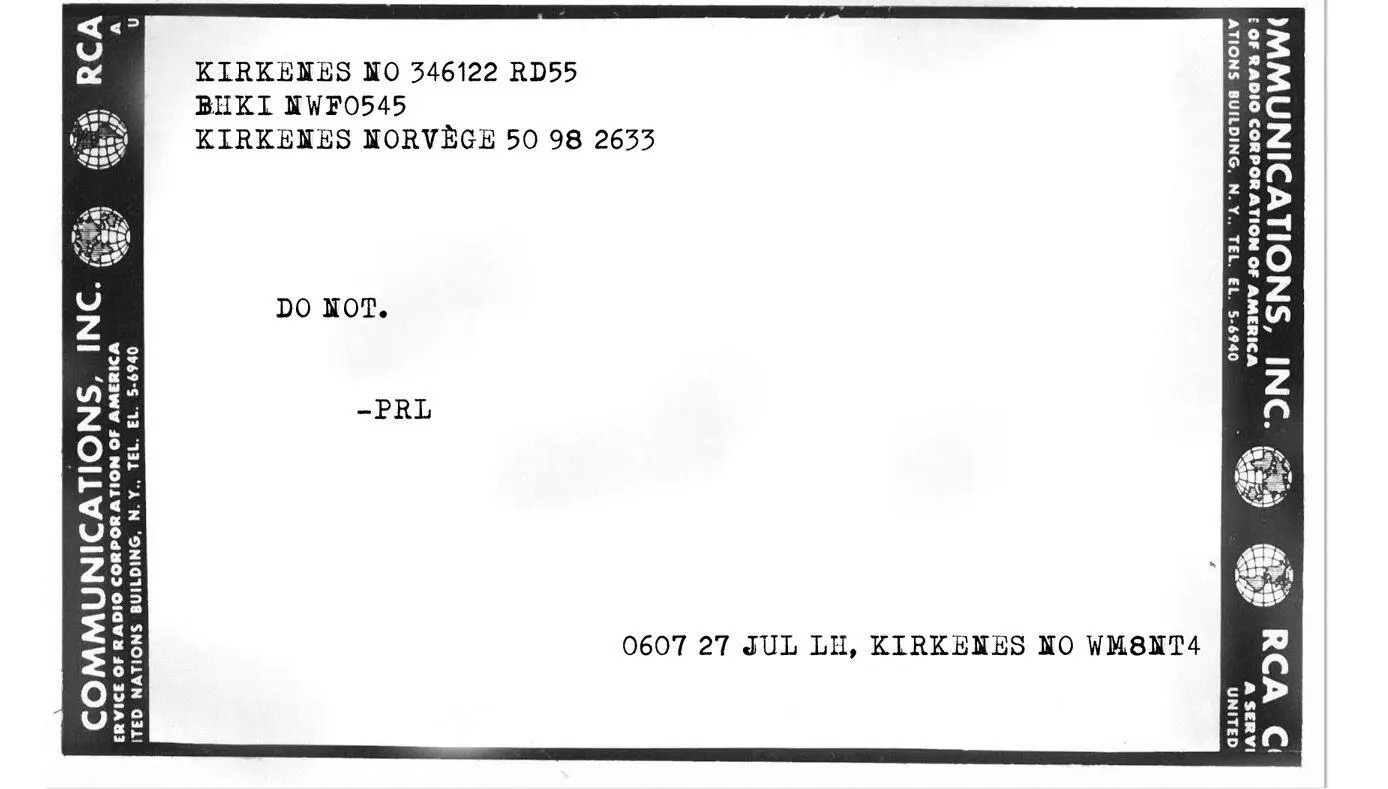

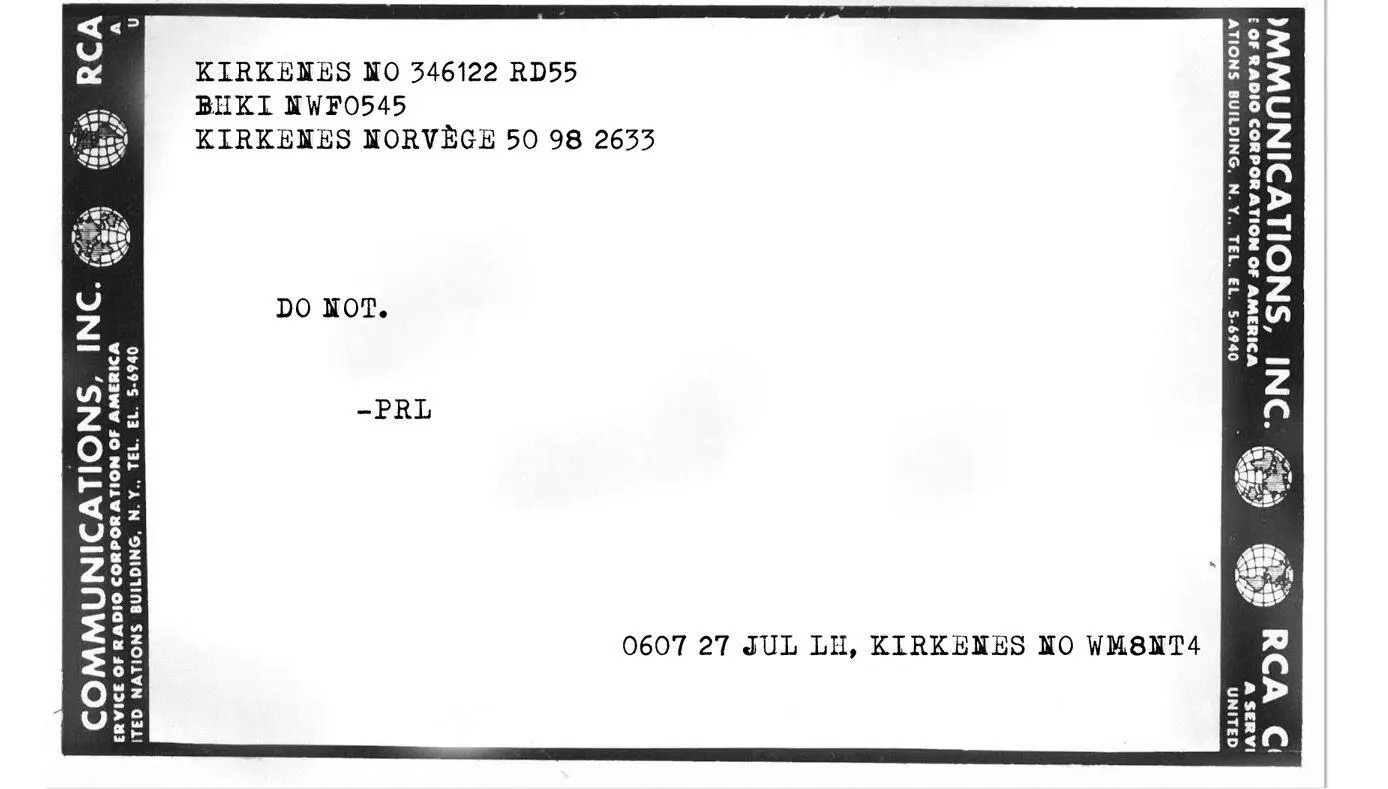

“A telegram came,” said Kermin.

“When?”

“This morning.”

“Who was it from?”

“I didn’t open it. It’s there.”

Before she had even picked it up, she knew.

The rest of the day fled toward a distant horizon. By that afternoon everything had been arranged. They stood outside the cabin that housed the vircator. The thin layer of snow had melted into a blanket of fog, relegating the sun to a distant memory. The air against their skin was cool and damp.

Several of the men they had seen before were now milling around, checking wires, writing on clipboards, looking unnecessarily busy. None of the men introduced themselves. Neither Jens, Siri, nor the boy Lars were anywhere to be seen. As preparations were made, Kermin sat on a half-moon boulder some distance away, a radio pressed to his ear, the faint patter of drums emanating from its speaker. Charlene found his newfound nonchalance about the whole matter slightly annoying. She wanted to go over and shake him. Do you realize what’s about to happen? Everything’s about to change.

Leif handed her a large plastic bottle of solution for Radar to drink.

“It’s to focus the current,” he explained.

“We’re going in there?” she asked, pointing to the large cabin.

“ He will be going in there,” he said. “I hope you can understand, but it’s not possible for you to be present during the actual procedure.”

“But he’s my son!”

“I’m sorry.”

Charlene thought she would protest more, but she simply nodded, fatigued, haunted by an unsettling feeling that she had seen this all before. The whole scene felt as if it had already happened. She had already been refused entrance to this cabin before. She had already remembered being refused entrance to this cabin before. She tried to shiver away these cycles of recall as she helped Radar drink all of the solution. Then she hugged him and turned him over to Leif.

Читать дальше