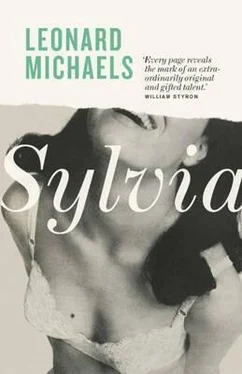

Leonard Michaels - Sylvia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leonard Michaels - Sylvia» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Sylvia

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sylvia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Sylvia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

draws us into the lives of a young couple whose struggle to survive Manhattan in the early 1960s involves them in sexual fantasias, paranoia, drugs, and the extreme intimacy of self-destructive violence.

Reproducing a time and place with extraordinary clarity, Leonard Michaels explores with self-wounding honesty the excruciating particulars of a youthful marriage headed for disaster.

Sylvia — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Sylvia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Despite righteous anger at the terrible boys, and sympathy for Agatha, it was impossible not to taste their nasty gratification. Her very harmlessness invoked torturers. Being rich and pampered was already potentially offensive. The expensive gifts, which the boys were unable to reject, pleased them and compromised them at once. In some strange way, the gifts seemed to beg for a return in affectionate cruelty. The boys did what she wanted them to do. They served her need to grovel, to feel pain, to collect experience for her stories. Otherwise, nothing happened to Agatha. She spent hours and hours shopping, but, aside from the time she spent with boys, she didn’t seem to live. She never had a conversation with anyone that she thought was worth repeating. She was never impressed by anything in Paris or Rome or wherever she vacationed; at least she never said what she’d seen or done in Europe unless it had to do with boys. She never mentioned a book. She did nothing athletic aside from the few sexual contortions in which she accommodated boys. She did go to movies, but she was never able to remember what the movies had been about, only what the actors looked like and maybe what they wore.

Nevertheless, she always had something to talk about. Lying on the couch in our small, roach-infested apartment, wearing the smartest frock from the smartest shop, Agatha produced her tales of abomination. It was her life. She was interested in almost nothing. She had everything she wanted. Every pleasure, every pain. From smart shop to sleazy joint, the limp, colorless bit of girl burned along the extremist cutting edge of the sixties until her mother had her committed to a Manhattan madhouse. When Sylvia heard it cost several hundred dollars a day, she was outraged. She didn’t want to visit Agatha, but finally the old feelings returned.

Agatha received us in a clean gray room — empty except for a bed, a table with a flower vase, and a chair — with barred windows, high above the city. She looked even softer and more languid. She looked chastened into quiet, spiritual composure. It was indeed a look. Plain and pure and holy. It was also sexy. The look was Agatha’s, not a designer’s. Basic Agatha, the look of her soul, her true, plain being. All connection with her former self, and the material world of glamour and depravity, had been severed. She looked good, and also like a good person.

We asked how she felt living in the hospital, incarcerated, under constant scrutiny. She answered by naming celebrities who had stayed in this hospital, and then she talked about several young people, presently among the inmates, who were marvelously interesting. She’d fallen among sensitive kids like herself. Artists, really, not lunatics. She had many new friends.

We’d gone to the hospital feeling pity for her. It was a cold dark day, and we’d had to walk against the wind for blocks and blocks, but it seemed necessary and decent to be doing this for Agatha. We felt good about ourselves. When we left the hospital the wind instantly reminded us of the painful streets, and we didn’t feel good anymore; we laughed at ourselves and hurried home feeling annoyed and foolish, like poor ignorant folks who’d had no idea that a hospital, even with bars on the windows, might be chic and fascinating. Agatha loved the place, was in no hurry to leave. She stayed about five weeks and came out a lesbian, having met and fallen in love with a wonderful crazy girl who treated her badly.

Only about twenty days before the wedding and we had a fight. Not worse than other fights but, the wedding so close, it felt more bitter, more wrong. I tried to get Sylvia out of bed at 8 a.m., when the alarm went off. She shrieked, slapped the blanket, demanded to be let alone. I cuddled and rocked her, trying very gently to get her out of bed. It was important to me — since we are getting married — that we begin trying to live in a normal, regular way. She knew what I thought, took it as a criticism. Refused to get up. Around noon she got up and said she wanted to buy some bras and a wedding dress. She wanted me to go with her. She insisted I go with her. I said I needed a shave; didn’t want to walk into a woman’s clothing store looking the way I did. The truth is I didn’t want to go. She said it didn’t matter how I looked. I shaved. We went. It was very windy and burning cold. She said that if she’d known how cold it was, she wouldn’t have insisted that I go with her. In a store on Eighth Street, she tried on two dresses. The first was red with a flat neck. It set off her complexion, eyes, and hair. She looked nice, but a red dress didn’t look right for a wedding. I don’t know why she bothered putting it on. Maybe she thought this dress would be an exception, as if there were a kind of red that a bride might wear. She did look good in it. The second dress was yellow and had a flared skirt. It made her look rather wide, and it brought out yellowish tones in her skin. Later, she said that my face had been ugly with disapproval in the clothing store. “You know I’m a pig, and I know I’m a pig,” she said. In the apartment again, she sat on the bed in her coat. Nothing had been accomplished. She hadn’t bought bras or a wedding dress. I said, “Let’s clean up this place.” She said, “Yes.” Her answer raised my spirits and I began to move about, picking things up. She noticed my show of energy, my optimism. She collapsed onto the bed, still in her coat, and she closed her eyes and started to go to sleep. I think I knew, before she collapsed, that I’d made a big mistake. My bustling about wouldn’t inspire Sylvia to do the same. But I couldn’t stop myself. It was my way of being insensitive, pretending not really to know her feelings, my way of not loving her. Seeing her lie there, in her coat, I quit trying to clean up. It was all very depressing, my stupid bustling and her collapse. I was more conscious than ever before of the havoc in our apartment, and in my heart. She keeps telling me that I think she is a pig. She doesn’t like her face, doesn’t like her body. I don’t want to love her anymore. Too hard. I’m not good enough.

JOURNAL, MARCH 1961

We went to the Village Vanguard, about five or six blocks from MacDougal Street, to see Lenny Bruce. The room was jammed and very dark. You couldn’t make out the ceiling, or the faces of people who stood along the bar. Hardly enough light for the waiters to pass between the tables. Light seemed concentrated in the spotlight on Lenny Bruce.

He wore a black leather jacket and had a hunched, scrawny, unwholesome, ratlike ferocity. His face, flattened and drained by the spotlight, looked hard, a poolroom face, not an entertainer. He began by reading a letter from a priest. It said Lenny Bruce is a moral genius, a great satirist. After reading the letter, Bruce began a routine made up mainly of shock words. He said “nigger,” “kike,” “spic,” while pointing to people in the audience. The audience tittered, laughed, then laughed more — and then — laughed as if we’d all gone over the edge, crazed by the annihilation of proprieties, or whatever had kept us from this until now. But Sylvia wasn’t laughing. She smiled tentatively, as if more frightened than amused.

Bruce said a word like “nigger” had power because it was suppressed. He spoke quickly. Nothing must be suppressed. We mustn’t keep ourselves from knowing how depraved we are. At once scary and hilarious, he seemed to make sense. Who could resist him? A hysterically funny dead-white ratface attacked political hypocrisies and puritanical attitudes toward sex. He did a long routine on the word “snot.” The word became the thing. He said imagine it on the sleeve of his suede jacket, shining, stiff, impossible to remove. He rushed toward the audience with the medal of snot on his sleeve. People shrieked with pleasure. Another routine was about a lady selling cosmetics, the Avon Lady, who came to Bruce’s house. She wanted to speak to his wife, who was in the bedroom, lying naked and unconscious in bed, sleeping off some drug. Bruce described himself dashing into the bedroom to make his wife presentable. He hung galoshes on her feet. Then he led the Avon Lady into the room. The audience laughed and screamed. In another routine, about an auto accident, Bruce made a picture of a man being lifted from a mangled car, half dead, bleeding heavily, in terrible pain. As he is carried to an ambulance, this man cannot help studying the beautiful ass of a nurse. The audience laughed and screamed. I laughed as much as anyone and felt a pleasing terror, like leaping from a high place. Now Sylvia was in tears, like a child, helpless with amazement, laughing. Our waiter stood beside our table, doubled over as if broken, clutching himself about the middle, paralyzed. Another waiter appeared and said, “Every fucking night this happens to you,” and put his arm around him and led him away, still doubled over, broken by laughter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Sylvia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Sylvia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Sylvia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.