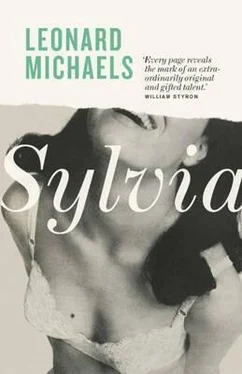

Leonard Michaels - Sylvia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leonard Michaels - Sylvia» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Sylvia

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sylvia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Sylvia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

draws us into the lives of a young couple whose struggle to survive Manhattan in the early 1960s involves them in sexual fantasias, paranoia, drugs, and the extreme intimacy of self-destructive violence.

Reproducing a time and place with extraordinary clarity, Leonard Michaels explores with self-wounding honesty the excruciating particulars of a youthful marriage headed for disaster.

Sylvia — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Sylvia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Why don’t you admit it?” she said.

If the saleslady was affectionate and sincerely attentive, Sylvia would buy anything from her. For every hundred dollars she spent on clothes, she got about fifty cents in value, and would have done better, at much less cost, in a Salvation Army thrift shop, blindfolded. When she liked some piece of clothing and felt good wearing it — a certain cashmere sweater, a cotton blouse, or her tweed coat with the torn sleeve — she’d wear it for days. She’d sleep in it.

Saturday was spent making up for Friday. We slept, made love, ate. I didn’t write, she didn’t study. We tried to sleep again, couldn’t sleep. Made love. Not well, but exhaustingly. She said, “You’re not natural.” We slept.

JOURNAL, MARCH 1961

My mother’s way of trying to help was to send food. I carried large grocery bags of bagels, fried chicken, potato latkes, cakes, and cookies to MacDougal Street. My father’s way was silence and looks of sad philosophical concern, which was no help, but he also gave me money. Our expenses were low, forty dollars a month for rent, maybe a little more for the food we kept in the refrigerator where it would be safe from roaches — spaghetti, oranges, eggs, coffee, milk, bread, and the pastries Sylvia loved. Gas and electric cost us about ten or eleven dollars a month.

The one time I tried to tell my father about my life with Sylvia, I became incoherent and suffered visibly. As in a dream, I couldn’t seem to say what I intended. My mouth felt weak and too big, my words sloppy. But he understood. Even before I did, he understood I was asking for his permission to do something terrible. He cut me off, saying, “She’s an orphan. You cannot abandon her.” A plain moral law. He couldn’t bear listening to me, seeing my torment. So he didn’t allow discussion, didn’t let me speak evil. Then he told about the wretchedness of husbands. He knew a man, seventy-seven years old, an immigrant Jew from Poland with a butcher shop on Hester Street, whose wife told the FBI he was a communist. They investigated him, and he spent nine days in jail. Fortunately, his name was good in the neighborhood. He wasn’t a communist. I got the point. Wives might do bad things to their husbands, but nothing could or should be done to end the miseries of the couple. The couple is absolute, immutable as the sea and the shore. With his little story, my father condemned me to marriage.

I’d wanted him to say something, but not that. I went away lonely and wretched. More than ever, I had to talk to somebody and I wondered about seeing a psychiatrist. In graduate school, I had read an essay on Jonathan Swift by the psychoanalyst Phyllis Greenacre. It was well written and, unlike much psychoanalytic writing, seemed conscious of literary values. Maybe I could talk to her. I thought about what I could say or dare not say. Finally, I dialed her number. She gave me an appointment.

Her living room was her office. A big room, with chairs and couches covered by lovely fabrics. The atmosphere was entirely domestic and pleasant, not the least medical. Had people come here to rave about their miserable lives? There were literary magazines, like the Hudson Review , on a coffee table. I felt out of place, not so much that I’d brought misery to this lovely room, but that I lacked the cultivation necessary to discuss my ugly case. Again I was having trouble talking. How could I say what brought me here? Where would I find the words? Where would I begin? Then I noticed Greenacre was suffering from an attack of hay fever, and it became hard to think about anything else. She was on the verge of sneezing, sniffling constantly, pressing tissues to her nose, trying to look at me through teary eyes. Her head was full of turbulent waters. It was discouraging.

I began by apologizing for not being able to talk objectively about my problems. I said I wasn’t sure I could get things right, or even review the events of my story correctly — what came first, what next. It was important, I said, no matter what I might say, not to misjudge Sylvia. I didn’t want to make her sound like something she wasn’t. Greenacre should be suspicious of every word I uttered. It was probably all lies. I’d try to tell the truth, but it was probably going to be a lie. My life, after all, wasn’t a story. It was just moments, what happens from day to day, and it didn’t mean anything, and there was no moral. I was unhappy, but that was beside the point, not that there was a point. I couldn’t be objective. I couldn’t be correct. I’d be entertaining, maybe, because that’s how I was. A fool. Greenacre interrupted:

“Just talk. Don’t worry about being objective.”

Her remark was very brutal, I thought; also embarrassing. She seemed not to appreciate how I’d been struggling to make clear the difficulty, for me, in saying anything, and therefore how amazing it was that I’d come this far, sitting here with a doctor, trying desperately to make it understood that I could never make anything clear, and the entire enterprise was worthless. Suddenly — jolted by her brutal interruption — I heard myself. I’d merely bumbled for five minutes. I’d been boring. I’d frustrated the doctor. If I had only this incoherent stuff to offer, she couldn’t do her job. I was virtually demented.

She waited, also struggling, if not against boredom then against hay fever for composure and concentration.

I then plunged ahead; talked for fifty minutes, withholding a little, but without being incoherent. She sniffled and responded to nothing, just took it all in. At the end, she said Sylvia and I both needed psychoanalysis. She would recommend someone, if I liked. She was no longer practicing, only acting as a consultant.

I asked if she had any idea about Sylvia and me, any impression she might be able to give me. She seemed reluctant to say another word. But I’d come across, told her so much. I was going to pay for the hour. With a shrug and a dismissive tone, she said, “You’re feeding on each other.”

Toward the end of our time on MacDougal Street, I convinced Sylvia to visit a psychiatrist at Columbia Neuro-psychiatric. A friend of Sylvia’s had been seeing him, and he said the doctor knew his business and was a decent guy. Sylvia let me make an appointment for her. The day of the appointment, Sylvia refused to get out of bed. I begged her. I argued and cajoled and yelled. Finally, I ran out the door, down the stairs, and hailed a taxi. I went to the appointment. It was extremely embarrassing. I explained as best I could. The doctor let me talk, listened to me for about an hour and a half. For the first time, I had no trouble talking. The bad scene with Sylvia before leaving the apartment, and the wild rush uptown, had thrust me into the middle of our saga. I talked about what happened minutes ago and what was happening day after day. I talked rapidly and lucidly, and I produced a voluminously detailed picture. At last, as if he’d heard something crucial, he said, “Has she started calling you a homosexual?” I told him about the Tampax. He said this is very serious. Sylvia ought to be committed. If I’d sign papers, he’d do the rest. He followed me to the head of the stairs, calling after me, “This is very serious.”

Maybe I’d wanted to hear him say something like that. Whether or not we were “feeding on each other” was less important than the fact that Sylvia was certifiably, technically nuts. This knowledge was horribly exciting. It made me very high. I ran to the subway, sobbing a little, running back to my madwoman. I’d been strengthened by new, positive knowledge, and a sense of connection to the wisdom of our healing institutions. As a result, nothing changed.

Awakened by a phone call. Sylvia, in a hurry to go to school, asks for the mailbox key on her way out the door. I say, “Will you let me know if I got any mail?” She says, “No. I need something to read during class.” She leaves. I hang up the phone. She comes back carrying a letter from my brother. She says, “Can I read it?” I say, “No.” She says, “Why not?” I say, “He might have intended it for me.” She shouts, stomps the floor, pulls the door shut with a great bang, runs down the stairs. I make coffee and gobble up half a loaf of bread without slicing it, tearing off wads, smearing the wads with butter, jamming them into my mouth.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Sylvia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Sylvia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Sylvia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.