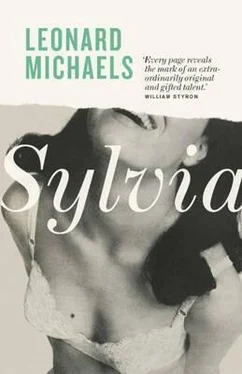

Leonard Michaels - Sylvia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leonard Michaels - Sylvia» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Sylvia

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sylvia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Sylvia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

draws us into the lives of a young couple whose struggle to survive Manhattan in the early 1960s involves them in sexual fantasias, paranoia, drugs, and the extreme intimacy of self-destructive violence.

Reproducing a time and place with extraordinary clarity, Leonard Michaels explores with self-wounding honesty the excruciating particulars of a youthful marriage headed for disaster.

Sylvia — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Sylvia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

JOURNAL, MARCH 1961

One evening, after another long fight, Sylvia went raging out of the apartment to take an exam in Greek, saying she would fail, she had no hope of passing, she would fail disgracefully, it was my fault, and “I will get you for this.” The door slammed. I sat on the bed listening to her footsteps hurry down the hall, then down the stairs. I was immobilized by self-pity, and, as usual, unable to remember how the fight had started, or even what it was about except that Sylvia was going to tell my parents about me, and report me to the police, and she would do something personally, too. In a spasm of strange determination, I got up, went out the door, and followed her through the streets to NYU. I was stunned and blank, but moving, crossing streets, walking through the park, then joining a crowd of students and entering the main building of NYU, following Sylvia down a hallway, up a flight of stairs, and down another hallway to her exam room. I stood outside the room and looked in. She sat in the last row and hadn’t removed her thin, brown leather wraparound winter coat, its tall collar standing higher than her ears. The coat was nothing against a New York winter, but Sylvia thought she looked great in it and wore it constantly, even on the coldest days. She was bent, huddled over the questions printed on her exam paper, as if the exam itself delivered heavy blows to her shoulders and the top of her head. Her ballpoint pen, clutched in a bloodless fist, moved very quickly, her face close to the page, breathing on the words she wrote. Five minutes after the hour, she surrendered the paper to her professor and came out of the room with a yellowish face, looking killed. When she saw me, she came to me without seeming in the least surprised, and whispered that she had been humiliated, had failed, it was my fault. But her tone was not reproachful. She leaned against me a little as we started away from the room. I could feel how glad she was to find me waiting for her. I put my arm around her. She let me kiss her. We walked home together, my arm around her, keeping her warm.

Her exam was the best in the class, and the professor urged her to persist in classical studies. She was pleased, more or less, but whatever she felt lacked the depth and intensity of her feelings before the exam. Her pleasure in being praised had no comparable importance, no comparable meaning. The success wasn’t herself. It had no necessity, like the shape of her hands or knees. It didn’t matter to her.

She didn’t always do that well; but considering how we lived, it was a miracle she passed any course. She took no pride in her success and never exhibited her learning in conversation, never referred to it. She was basically uninterested; only performing. Academic achievements, to her, were an embarrassment.

“I’d give thirty points off my IQ for a shorter nose.”

“Nothing is wrong with your nose.”

“It’s too long, a millimeter too long.”

Agatha Seaman, who lived in Yonkers and visited Sylvia regularly, told her about a doctor in Switzerland who could reshape her nose without surgery, molding it by hand over a period of weeks at his clinic in the Alps, where you could also ski and the meals were marvelous. “Everybody goes there.” Sylvia cared less about the shape of her nose than its length, but she yearned for the mythical doctor. He’d been mentioned in a fashion magazine and described as the darling of European society. Sylvia was resentful of Agatha, because she could easily afford to spend weeks at the alpine clinic. Not that Sylvia would go if she could afford it. Still, she wanted to believe there was such a doctor, and hope existed for her nose, and it was available to her, not just Agatha.

I liked Sylvia’s nose, but I said nothing, certainly nothing about the fantasy doctor. I might easily say the wrong thing. My idea was that Sylvia wanted someone to do to her nose what she did to her dresses, which was to change them. She changed their length or width, or removed a collar or added a collar or tightened the shoulders. She always ruined her dresses, or else she decided, after much cutting and sewing, that the changes didn’t work for her. There were dozens of beautiful dresses and skirts, purchased with inheritance money soon after her mother’s death. None of them fit like another. They were stuffed into boxes and suitcases that were jammed under the couch and in the back of the closet and almost never opened. She wore only a few things and she had no memory of the extent of her wardrobe, no idea of how many thousands of dollars she had spent on clothes. Since she often fell asleep in her clothes — too depressed or too lazy to undress, or because she felt good in what she was wearing — she wore the same thing for days while hundreds of pieces of clothing, altered and realtered, were simply forgotten and never worn.

I hoped that she’d leave her nose alone. As for Agatha’s doctor, he was like everything else in her life, an extravagant fantasy somehow related to boys. Agatha was subject to passionate fixations on boys, always younger than she, and always poor, ignorant, dark — Arab, Turk, Italian, Puerto Rican — sublimely handsome, and invariably vicious. If they weren’t vicious when they met Agatha, she helped them discover it in themselves. Then she told Sylvia about it. Sylvia told me. Month after month, I heard about the boys.

Sprawling for hours on our couch, Agatha would tell Sylvia exceedingly detailed stories about the boys — how last night she waited in an alley behind the hotel where Abdul or Francisco or Julio worked as a bellhop or a busboy, and when he appeared after work, she surprised him. The boys were outraged by these surprises, but Agatha always brought gifts — jewelry, leather jackets, luscious silk shirts — tickets of admission to their lives. Trembling with humility and fear, she held the gift toward the boy. Unable to reject it, he relented, and she’d follow him down the street as he fondled the gift, maybe tried it on. Sylvia imitated Agatha imitating herself, whimpering about how gorgeous he looked, how she’d been absolutely right, “Magenta was Abdul’s color” or “Francisco looked divine in black silk.”

Gradually, the boy’s anger gave way to a different, yet related feeling. The boy would lead Agatha into a doorway or a phone booth where he might allow her to blow him. Sometimes he’d turn her around and abuse her from behind, then leave her burning and bleeding and go to meet his real date. Agatha referred to the boy’s date as “a mean selfish bitch.” With monotonic matter-of-factness, she told Sylvia exactly what the boys did to her. She never seemed to notice that her stories always followed the same pattern — passionate fixation, gifts, debasement, abandonment. Her stories were true, I think, but so much the same it began to seem Agatha was enslaved by the pattern, living to do it again and again and to tell Sylvia that it had happened again. Telling about it was masturbatory, but just as important as the real experience; maybe more important, or maybe there was no difference any longer for Agatha. She and Sylvia would lie about for hours, sometimes drawing portraits of each other as they drank tea and Agatha told her story. They looked beautifully civilized in their intimacy.

Agatha, always giving the boys gifts, might have been a gift sufficient in herself — a slender blonde about the same size and shape as Sylvia — but she indulged an enervated, unattractive manner. Her voice, kept low and dull to suggest feminine reserve, suggested instead a low-voltage brain and morbidity. Her complexion, embalmed for years in cosmetic chemicals, had the texture of tofu.

Contempt, pity, prurient fascination, and affection bound Sylvia to Agatha. I liked her, too, and also felt the other things. She had a sickly, languid manner, making her seem physically weak, and an air of fear and injury, which gave her the appeal of a doomed kitten. A small face with light blue staring eyes; a small mouth with lips that hardly moved when she talked. Nobody was more harmless or perversely exciting. The boys sometimes beat up Agatha, but she never seemed to bruise or scar, at least not visibly. There was no tension in her. Nothing resisted; nothing broke.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Sylvia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Sylvia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Sylvia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.