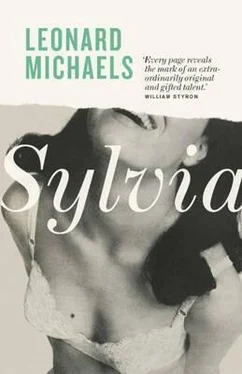

Leonard Michaels - Sylvia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leonard Michaels - Sylvia» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Sylvia

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sylvia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Sylvia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

draws us into the lives of a young couple whose struggle to survive Manhattan in the early 1960s involves them in sexual fantasias, paranoia, drugs, and the extreme intimacy of self-destructive violence.

Reproducing a time and place with extraordinary clarity, Leonard Michaels explores with self-wounding honesty the excruciating particulars of a youthful marriage headed for disaster.

Sylvia — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Sylvia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sylvia said she didn’t do well on the Greek test. She was wildly remorseful. Wouldn’t have sex. Got out of bed to brush her teeth, then had a small crying fit at the kitchen sink, and said, “I don’t want to get married.”

I lay there thinking that it will make my parents miserable if I call off the wedding. I will have disappointed them again. I will fail in everything and Sylvia will go completely nuts. Then I thought we will get married, and I will bring our child with me when I visit Sylvia in the nuthouse.

I won’t go mad. Not me. Mindless sanity sustains me. I am an ordinary person. I don’t know Latin and Greek. All I know is how to work. I went to my room and sat at the typewriter. My feet began to freeze, my knees felt numb. There was a steady crash of wind and rain against the window. Sylvia went back to bed. She might sleep until morning, I thought.

JOURNAL, MARCH 1961

In those days R. D. Laing and others sang praises to the condition of being nuts, and French intellectuals argued for allegiance to Stalin and the Marquis de Sade. Diane Arbus looked hard at freaks, searching maybe for a reservoir of innocence in this world. A few blocks east, at the Five Spot, Ornette Coleman eviscerated jazz essence through a raucous plastic sax. The great Charlie Mingus was also there, playing angular, complex, hard-driving music to a full house night after night. In salient forms of life and art, people exceeded themselves — or the self; our dashing President, John F. Kennedy, was screwing movie actresses. Everything dazzled.

Movies, the quintessence of excess, were becoming known as “films.” To the reflective eye, Antonioni’s movies were among the most important. Sylvia and I never missed one. We’d emerge radically deadened, yet exhilarated, sorry the movie had to end. She whispered once, as the lights came on, “Why can’t they leave us alone?” It was truly painful, having to thrust back into the windy streets, back to our apartment. We carried away visions of despair and boredom, but also thrilling apprehensions of this moment, in this modern world, where emptiness could be exquisite, even a way of life, not only for Monica Vitti and Alain Delon but for us, too. Why not? Feelings were all that mattered, and they were available to us. We understood. We were susceptible to the ineffable strains and moods of modern life. We’d read Nietzsche. Our brainiest friends — not only sad little Agatha — brought regular news from the abyss. One of them, a graduate student in art history, was on heroin. Another, whose translations of Chinese poetry had won awards and a book contract, strolled the wall beside the Hudson River, a willing prey to rough trade.

I would come back to the apartment after shopping for groceries, or doing the laundry — Sylvia never did these things — and find Agatha lying about, telling all. I could hardly wait to hear it from Sylvia, stories about the wilderness of Manhattan where Agatha descended nightly. When she stayed very late, I’d walk her down into the street, then wait with her for a cab. I worried about her. She might run into trouble — hapless, defenseless girl — alone in the dark. I refused to acknowledge that she was excited by dangers of the unknown, running after trouble in the dark.

“It’s too cold to wait out here,” she said.

“No bother. I want to do it.”

I peered down the avenue, freezing, praying for a cab to appear and take Agatha away. Then I hurried back to Sylvia. Agatha had told Sylvia how a boy forced her into prostitution. He took her to a boat docked on the West Side, then down into a small room. He kept her there until the men came, bestial types. While one did things to her, others watched. I imagined a steel room in the bottom of the boat, echoing with animal noises.

Repeating it to me — the boat, the small room, the men — Sylvia was ironically amused, posturing in her voice, mimicking Agatha’s dull tones, as if to measure the distance between Agatha’s lust for degrading experience and herself. I listened, feeling entertained without feeling guilty. I let myself imagine that Agatha was far gone, beyond recall, object more than subject, without claims on my humanity. I owed only politeness. A few minutes in the street waiting for a cab. What sympathy I felt was easy. Liking her was also easy. Affectations, corrosive cosmetics, stylish clothes, an aura of self-destructive debauch — she was utterly harmless, even sort of cute. I liked myself for liking her. She reported every peculiarity of her soul to Sylvia, but I didn’t see, beneath Sylvia’s contempt in retelling the stories, that she was involved in Agatha’s fate. Then, one night in bed, Sylvia said, “Call me whore, slut, cunt. .”

I was eventually to call her my wife. The old-fashioned name would make our life proper, okay. Things would change, I believed, though our fights had become so ugly that the gay couple across the hall wouldn’t ever say hello to us. We passed frequently, almost touching, along the dingy route to the hall toilets, one dank closet for each apartment. They turned up their phonograph until it boomed above our shrieking. Eighteenth-century pieces, wildly flourishing strings and an extravaganza of golden trumpets, as if to remind us of high, vigorous civilization, where even the most destructive passions are sublimed. They hoped to drown us, maybe shame us, into silence. It never happened.

It’s possible we frightened them with our horrendous daily battles, but I assumed they just didn’t like us. They were repressed Midwestern types. Towheaded, hyperclean, quiet kids in flight from a small town, hiding in New York so they could be lovers, never supposing that their neighbors, just across the hall, would be maniacs. It struck me as paradoxical that being gay didn’t mean you couldn’t be disapproving and intolerant. I liked eighteenth-century music. Couldn’t they tell? Forgive a little? Were their domestic dealings, because they behaved better, so different from ours? Sharing a bed, were they never deranged by sexual theatrics or loony compulsions? They passed us with rigid, wraithlike, blind faces. No hello, no little nod, only the sound of old linoleum crackling beneath us. They pressed toward the wall so as not to touch us inadvertently. We were an order of life beneath recognition. Their soaring music damned us. Their silence and their music threw me back on myself, made me think Sylvia and I — not the gay kids — were marginal creatures, morally offensive, in very bad taste. We were, but they seemed unjust. They really didn’t know. I didn’t either as I held Sylvia in my arms and called her names and said that I loved her. Didn’t know we were lost.

I have no job, no job, no job. I’m not published. I have nothing to say. I’m married to a madwoman.

JOURNAL, JANUARY 1962

Soon after we were married, Sylvia said, “I have girlfriends who make a hundred dollars a week,” which was a good salary in the early sixties. It would have paid two months’ rent and our electric bills. But Sylvia meant, compared to her girlfriends, I was a bum. Eventually, I published a story or two in literary magazines, which made me happy, but the magazines paid nearly nothing. So I began looking for a job and, to my surprise, I was hired almost immediately as an assistant professor of English at Paterson State College in New Jersey. Then I stopped writing. I had much less time for stories, but more important was the fact that I was married. It changed my idea of myself. As a married man, I had to work for a living. I’d never believed writing stories was work. It was merely hard. The sound of my typewriter, hour after hour, caused Sylvia pain, and this was another reason to stop. But then whatever had importantly to do with me — family, friends, writing — shoved her to the margins of my consciousness, and she’d feel neglected and insulted. This also happened if I stayed in the hall toilet too long, and it happened sometimes when we walked in the street. I’d be talking about a friend or a magazine article, maybe laughing, and I’d suppose that I was entertaining her, but then I’d notice she wasn’t beside me. I’d look back. There she was, twenty feet behind me, down the street, standing still, staring after me with rage. “You make me feel like a whore,” she said. “Don’t you dare walk ahead of me in the street.” Then she walked past me and I trailed her home, very annoyed, but also wondering if there wasn’t in fact something wrong with my personality — talking, laughing, and having a good time, as if, like a moron or a dog, I was happy enough merely being alive. At the door to our building, Sylvia waited for me to arrive and open it for her, so that she could feel I was treating her properly, like a lady, not a whore.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Sylvia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Sylvia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Sylvia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.