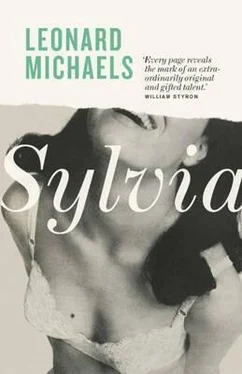

Leonard Michaels - Sylvia

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leonard Michaels - Sylvia» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Sylvia

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sylvia: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Sylvia»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

draws us into the lives of a young couple whose struggle to survive Manhattan in the early 1960s involves them in sexual fantasias, paranoia, drugs, and the extreme intimacy of self-destructive violence.

Reproducing a time and place with extraordinary clarity, Leonard Michaels explores with self-wounding honesty the excruciating particulars of a youthful marriage headed for disaster.

Sylvia — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Sylvia», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Another time she pulled all my shirts out of the dresser and threw them on the floor and jumped up and down on them and spit on them. I seized her wrists and pressed her down on the bed while I shouted into her face that I loved her. By tiny degrees, she seemed to relax, to relent. I urged her along, more observer than committed fighter, and I sensed the changes she passed through, each degree of feeling.

After a fight, unless there was sex, Sylvia usually collapsed into sleep. Ringing with anguish, exceedingly awake, I forced myself to rethink the fight, moment by moment, writing it all down in the cold room as Sylvia slept. It was my way of knowing, if nothing else, that this was really happening. It was also a way of talking about it, though only to myself. I hid the journal in a space just below the surface of the table where I wrote stories. None of the stories were about life on MacDougal Street. My life wasn’t subject matter. It wasn’t to be exploited for the purpose of fiction. I’d never even talked about it to anyone, and I imagined that nobody knew how bad things were. As a matter of high principle and shame, I kept everything that happened on MacDougal Street to myself. By sneaking the events into my journal, when Sylvia collapsed, I made them seem even more secret. Then, one afternoon, Malcolm Raphael, another old friend from the University of Michigan, visited. We were alone in the apartment. He said he’d just come from Majorca, where he’d overheard some Americans, lying near him on the beach, talking about me and Sylvia. One of them lived in our building. He described our fights to the others.

I felt myself going blind and deaf, repudiating the news, denying it in my physiology. It was like fainting. Malcolm saw my reaction, laughed, and told me about the fights he’d had with his wife. It was an extraordinary moment. Men never talked to each other this way. His fights were as bad as mine, but he made them seem funny. He was unashamed.

I was grateful to him, relieved, giddy with pleasure. So others lived this way, too, even a charming, sophisticated guy like Malcolm. We laughed together. I felt happily irresponsible. Countless men and women, I supposed, all over America, were tearing each other to pieces. How great. I was normal. It was a delightful feeling, but to think this way also gave me the creeps. I was reminded of some former acquaintances, flamboyant gay kids I’d met years ago, while learning how to skate at Iceland, the rink next to Madison Square Garden. I’d find them speeding about, slashing ice, or gathered at the edge of the rink watching the skaters and gossiping. They referred to everyone as a “faggot.” The cop we passed in the street was a “cop-faggot.” The mayor of New York was a “mayor-faggot.” A famous football player was a “football-faggot.” Every “he” was a “she.” The more manly, strict, correct, official, moral, authoritative, the more faggot she.

Now, after listening to Malcolm, I felt like the gay kids — shame notwithstanding — onstage, my secret life subject to the voracious curiosity of everybody, and in their gayish manner, I let myself think every man and woman who lived together were like Sylvia and me. Every couple, every marriage, was sick. Such thinking, like bloodletting, purged me. I was miserably normal; I was normally miserable. Whatever people thought of me, I could think it first of them. I could flaunt my shame as a form of contempt for others. No better disguise for shame than contempt, and nothing is easier to do than to sneer and denigrate. Nothing is more pleasing to the vanity of others. Any two people chatting are making invidious remarks about a third. It is a perverse form of generosity, and self-adoration.

Sylvia knew nothing about the gossip. Since she lived in constant fear of humiliation, I didn’t tell her. The fact that our cover was blown strengthened my commitment to her. She’d really been hurt, virtually killed, even if she didn’t know it. We weren’t yet married, but Sylvia wanted to do it soon, and the simple idea that it would be unwise for us to marry did not occur to me. If I did not want to marry Sylvia, I couldn’t think I didn’t, couldn’t let myself know it. I had no thoughts or feelings that weren’t moral. When I added two and two, a certain moral sensation arrived with the number four.

Sylvia complained again of a swollen spot on the back of her neck. I rubbed the area for a little while. I felt nothing swollen. Anyhow, the complaining stopped. I then said I wanted to go do some work. She said she had a stomachache. I didn’t believe her, and I despised myself for not believing her. She needed comfort. Whether or not she had real pain was irrelevant. She lay on her stomach and moaned in different ways, emitted small shrieks. I asked her to stop, turned her over. She moaned through bared teeth, her eyes wide and fixed on mine. I cupped her mouth. She bit my hand, then sobbed and said I could go. She wanted me to go. I could continue living with her if I liked, but I was also free to go. She let me hold her. I cried a little, kissing her, holding her. I showed love, but it felt like a self-accusation, or an apology. That was my apology — very sincere — but it was for nothing specific. Like a religious convulsion. You apologize for being alive, for not being sick, for not being physically deformed, for not being as bad off as other people. I don’t know what I apologized for. Maybe for the love I desecrated by not believing in Sylvia’s pain. I felt utterly sincere, apologizing, kissing her. It was too delicious, I think.

JOURNAL, MARCH 1961

I was affected by cultural radiations from newspapers, radio, movies, television, but my life was MacDougal Street, voices through the walls, traffic noises through the windows, odors floating up the stairwell, and always Sylvia. A visit to my parents lasted only a few hours. There was no place to go where I might forget MacDougal Street and Sylvia for a little while.

With few exceptions, Sylvia imagined my friends were her enemies. Once, hurrying back to the apartment from a twenty-minute meeting with a friend in the San Remo bar, a hundred feet from the entrance to our building, I opened the apartment door on madness. Sylvia, at the stove, five feet away, turned toward me holding a plate of spaghetti in her hand — already startling, since she never cooked — and the plate came sailing toward my face, strands of spaghetti untangling like a ball of snakes. “Dinner,” she said. I caught it against my forearm.

She’d been enraged by my meeting downstairs, so she cooked spaghetti. Why? She saw herself standing at the stove and cooking spaghetti like a woman who does such things for a man. The man, however, being viciously ungrateful, abandoned her. While Sylvia slaved over a boiling pot of spaghetti, I regaled myself with conversation and a glass of beer. In a bitterly hideous way, it struck me as funny, but I wasn’t laughing.

The telephone, if it rang for me, was also her enemy. She’d say, “His master’s voice,” and hand me the phone. After I put it down, she’d jeer, “You love Bernie, don’t you?” He was a witty guy. I’d laughed too hard at his remarks during the phone call, and Sylvia resented all that flow of feeling in his direction. Eventually, when answering the phone, if Sylvia was in the room, I kept my voice even and dull, or edged with annoyance, as if the call were tedious. I learned to talk in two voices, one for the caller, the other for Sylvia, who listened nearby in the tiny apartment, storing up acid criticisms.

I liked Sylvia’s friends, and I was glad when they phoned or visited. They proved Sylvia was lovable, and they let me believe that we were good company. I wanted Sylvia to have lots of friends, but she was carefully selective and soon got rid of her prettiest girlfriends, keeping only those who didn’t remind her of her physical imperfections. In a department store, if a saleslady merely told Sylvia that a dress was too long for her, she took it as a comment on her repulsive shortness. If a saleslady said bright yellow was wrong for Sylvia, it was a judgment on her repulsive complexion. She would quickly drag me out into the street, telling me that I thought the same as the saleslady.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Sylvia»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Sylvia» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Sylvia» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.