It was surprising how quickly this became a burden.

It had been raining for days. A succession of black clouds crawled above Barrow. And what wind! Small things and bits of paper were taken into the air, held, then tossed, as if Lambton County were sullenly looking for something it had lost. Day was as dark as evening, evening as dark as night.

On one of these evenings, Robbie waited for Liz in his room. To create an atmosphere, he had set out slices of Harrington’s raisin bread, toasted, on a plate, so that his room smelled of yeast and raisins. Beside the plate, there was a candle in a blue cup: a white candle, some eight inches tall, its wax congealing into perfectly formed droplets along its body.

Liz had asked to see him. No doubt, she had something to say about Atkinson’s. Well, she could say what she wanted and he would listen, but he felt he was a better person for having faced his fears and he didn’t care when people kidded him about making his shortcomings public. Besides, something had shifted in him. He was not as sure as he should have been that he wanted to marry Liz. Feeling as he did now, the right thing would have been to marry Jane.

And yet, the more he thought about how much he wanted Jane, the more vividly images of Liz would come to him: Liz’s upper torso, from the bottom of her neck on down, her white robe gaping, most of one breast visible, and her right hand, its long fingers holding the robe closed. A memory like that was imperious, dismissing everything before it. What he would have given to master words! How he wished he could share his feelings with the women he loved.

When Liz knocked at the front door, he let her in and took her up to his room, where the smell of raisin bread had given way to something still yeasty but more burnt. God only knows why she loved this smell, but as it gave her pleasure he did not mind.

The look on her face was impossible to read, and Robbie was suddenly unsure of himself.

— Is everything okay? he asked.

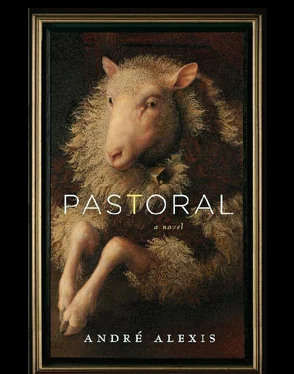

She looked around as if taking the room in for the first time. There was the narrow bed in which they had managed to sleep, side by side, when his parents were away, the coverlet with its blue and white chessboard squares on which there were drawings of the same objects repeated over and again along the white diagonals: a candle, a sheep, bread, a stream, an open book. The walls were light blue, uninterrupted save for the generic painting of a schooner, a painting Mrs. Myers had chosen for the room shortly after Robbie’s birth. There was a chest of drawers, a desk that Robbie never used and a bookshelf half-filled with books Robbie had never read: bound copies of Reader’s Digest , mostly. On the floor there was a crimson-and-red throw rug from somewhere exotic (Iran, his mother said), bought from a Middle Eastern gentleman at a garage sale in Leamington.

— I’m not going to marry you, said Liz.

No one who knew their situation would have been surprised, but Robbie plaintively asked

— Why?

— Where do you want me to start? she said.

A fair question to which there was only one important answer or one true counter-question: did this ending matter to him?

— You know I love you, he said.

— You went into the hairdresser’s for Jane. You wouldn’t have done that for me.

— Who told you that? It’s not true! I didn’t do it for Jane! You didn’t ask me! I’ll do it now if you want.

— No thank you, she answered.

Elizabeth had meant to say all manner of things. She’d meant to remind him of the pain he’d put her through and of her unwavering fidelity. In her imagining of this last moment between them, there was some back and forth: a heartfelt (but too late) apology from him, the assurance that he would never put her through such misery again, the assurance that he would never see Jane Richardson again. In her imagination, this final moment had been something of a quiet triumph. But, in fact, it was all unbearably sad. She felt no more triumph than she would if she had been looking down at a precious vase shattered on a kitchen floor. She hadn’t the least interest in his last words. She was finished with him. And yet she still found it difficult to get up from the bed and leave. Leave him, leave the past they shared, leave the future they had planned.

She waited in silence, as Robbie tried to find something appropriate to say.

— But I do love you, he said at last.

His one endless note, a note that now turned all her nostalgia and longing to spite.

— I don’t love you , she said.

And rose to leave.

And then left, there being no words to make her stay.

Robbie had not anticipated this moment. In fact, he had never really thought it possible. When Elizabeth had gone, it seemed to him as if he’d witnessed an accident. Was it his fault that he loved two women at once? Had he asked for such a thing? He had been honest (well, eventually honest), hadn’t he? He was a good man in unfortunate circumstances, nothing less. Seeing Liz get up and leave was like the moment immediately after you’ve bumped into something — a vase, say — and you put your hands out to catch it, only to see it fall (not quite inevitably) to the floor.

Robbie did not think these things. He felt them, obscurely, as if through a fog of other feelings. He had an intuition of loss but ignored it, reassured that, after all, there was Jane, that he could build a life with Jane, that Jane was more exciting than Liz, more likely to bring him unpredictable joys. By the following day, he almost believed that losing Liz was the best thing that could have happened. Love or no love, did he really want the domesticity that went with marriage? No, maybe, never mind. Nevertheless, he’d almost certainly dodged a bullet by avoiding the wrong marriage. Hadn’t he?

As soon as he could, Robbie told Jane the good news.

It was, of course, news that Jane knew better than he did. She had been thinking about nothing else since she’d won her wager with Liz Denny. She had also been thinking about the unfortunate deal she’d made with herself. Robbie had done what she’d asked. She had won, so she could not flee to her mountain. She was, if she played by the rules she herself had set, doomed to live in Barrow.

For weeks Jane tried to live honourably, accepting her agreement with herself as a given. She was to live with Robbie Myers? Fine. But she could surely find some way to influence him, to turn him into the kind of man she now knew she wanted. What kind of man was that? Someone who read books, not just magazines. Someone interested in more than cows and sheep. Someone curious about the world outside Lambton County; a man who knew the difference between Paris and La Paz. A man who could entertain her with his wit, not just his muscles and nethers. It wouldn’t hurt, either, if he knew a foreign language. French would do, even bad French if he showed ambition to learn. A man who smelled of something other than Ivory soap and Tide detergent. A man whose touch was subtle, one who didn’t go at your nipples like taking a bolt off a tractor.

In a word, she was looking for someone other than the man who was now hers.

No surprise: her resolve to remain in Barrow weakened quickly. Knowing the kind of man she wanted, now that she had one she did not want, she soon understood she would never be happy with Robbie. Nor would anyone have blamed her for leaving a man she no longer loved. She did cause ‘poor young Myers’ some distress before she left, though, in part because she wanted to see if she could change him for the better, in part because she needed to feel the true inanity of a life with Robert before she could find the strength to cut herself permanently off from her roots.

Jane began her experiment with Robbie one rainy night in late summer. They were at her parents’ house while her parents were away. She and Robbie had made love, mostly because she’d felt it a duty to sleep with him. Predictably, it hadn’t gone well. She’d gotten almost no pleasure out of his exertions and felt only slight gratification when he did. It hadn’t been Robbie’s fault per se. He did as he always did. That is, he did more or less what she told him to and enjoyed it. But she’d felt empty. Taking up one of several books by the side of her bed, she said

Читать дальше