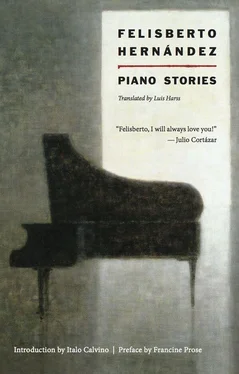

Felisberto Hernandez - Piano Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Felisberto Hernandez - Piano Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: New Directions, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piano Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piano Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piano Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Piano Stories

Piano Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piano Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Tell me the truth. Why did the woman in your story commit suicide?”

“I’m afraid you’d have to ask her.”

“Couldn’t you ask her for me?”

“No more than I could ask something of a figure in a dream.”

She smiled and lowered her eyes, and I got a good look at her large mouth. It seemed the smile could go on stretching her lips forever, but I passed my eyes over their entire moist red surface with pleasure. Maybe she was watching me through her eyelids or wondering whether there wasn’t something guilty in my silence, because she dropped her head on her chest and hid her face. Now she was showing me her full head of hair. Between two waves I could see a bit of scalp and it reminded me of the skin of a hen when the wind ruffles her feathers. I enjoyed thinking of that head as a big, warm human hen: it would give out a delicate warmth and the hair would be like very fine feathers.

One of the aunts — not the one with the smoked eyes — brought us two small glasses of liqueur. The niece raised her head and the aunt said:

“Watch out for this one, he looks sly as a fox.”

I remembered the hen and said:

“But we’re not in a henhouse!”

Alone with me again, as I tasted the liqueur — it was too sweet and turned my stomach — the niece asked:

“Aren’t you ever curious about the future?”

She had puckered her mouth as if to tuck it into her glass.

“No, I’m more curious about what’s going on at this moment inside another person or what I’d be doing right now if I were somewhere else.”

“Tell me what you’d do if I weren’t here right now.”

“As a matter of fact, I’d pour my drink into this flower vase.”

I was asked to play the piano. The two widows were huddled in the parlor, the one with the smoked eyes bending an ear to receive her sister’s urgent whispers. The creaky little piano was out of tune. I didn’t know what to play, and the minute I tried some notes the widow with the smoked eyes burst into tears and we all fell silent. Her sister and her niece helped her out of the room. A moment later the niece came back in and said her aunt could not stand the sound of music since the death of her husband: they had been in love into dim old age.

Some of the guests were leaving, and the rest of us began to lower our voices in the fading light. No one had lit a lamp.

I was one of the last to go, stumbling over the furniture. In the entrance hall the niece stopped me and said:

“Will you do something for me?”

But then she just leaned her head back against the wall, holding on to my jacket sleeve.

The Balcony

I liked to visit this town in summer. A certain neighborhood emptied at that time of the year when almost everyone left for a nearby resort. One of the empty houses was very old; it had been turned into a hotel, and as soon as summer came it looked sad and started to lose its best families, until only the servants remained. If I had hidden behind it and let out a shout, the moss would have swallowed it up.

The theater where I was giving my concerts was also half empty and invaded by silence: I could see it growing on the big black top of the piano. The silence liked to listen to the music, slowly taking it in and thinking it over before venturing an opinion. But once it felt at home it took part in the music. Then it was like a cat with a long black tail slipping in between the notes, leaving them full of intentions.

After one of those concerts, a timid old man came up to shake my hand. The bags under his blue eyes looked sore and swollen. He had a huge lower lip that bulged out like the rim of a theater box. He barely opened his mouth to speak, in a slow, dull voice, wheezing before and after each word.

After a long pause he said:

“I’m sorry my daughter can’t hear your music.”

I don’t know why I imagined his daughter was blind, although I realized at once that that would not have prevented her from hearing me, so that she was more likely deaf or perhaps out of town — which suddenly led to the idea that she might be dead. Yet I was happy that night: everything in that town was quiet and slow as the old man and I waded through leafy shadows and reflections.

Suddenly bending toward him, as if sheltering some frail charge, I caught myself asking:

“Your daughter couldn’t come?”

He gasped in apparent surprise, stooped to search my face and finally managed to say:

“Yes, that’s it. You’ve understood. She can’t go out. Sometimes she can’t sleep nights thinking she has to go out the next day. She’s up early in the morning preparing for it, getting all excited. But after a while it wears off, she just drops into a chair, and she can’t do it.”

The people leaving the concert soon disappeared into the surrounding streets and we went into the theater café. He signaled the waiter, who brought him a dark drink in a small glass. I could only spend a few minutes with him: I was expected elsewhere for dinner. So I said:

“It’s a shame she can’t go out. We all need a bit of entertainment.”

He had raised the glass to his big lip but interrupted the motion to explain:

“She has her own way of keeping entertained. I bought an old house, too big for just the two of us, but it’s in good shape. It has a garden with a fountain and in her bedroom there’s a door that opens onto a winter balcony. It’s a corner room, facing the street, and you could almost say she lives in that balcony. Or sometimes she goes for a walk in the garden and on some nights she plays the piano. You can come and have dinner with us whenever you want and I’ll be grateful to you.”

I understood at once. So we agreed on a day when I would go for dinner and play the piano.

He called for me at the hotel one afternoon when the sun was still high. From a distance, he showed me the corner with the winter balcony. It was on a second floor. The entrance to the house was through a large gate on one side. It opened onto a garden with a fountain and some statuettes hidden in the weeds. Around the garden ran a high wall. The top of the wall was all splintered glass stuck in mortar. A flight of steps led up into the house, through a glassed-in corridor from which one could look out at the garden. I was surprised to see a large number of open parasols in the long corridor. They were different colors and looked like huge hothouse plants. The old man hastened to explain:

“I gave her most of the parasols. She likes to keep them open to see the colors. When there’s nice weather she picks one and goes for a short walk in the garden. On windy days you can’t open this door because the parasols blow away, we have to use another entrance.”

We reached the far end of the corridor by going along the space left between the wall and the parasols. We came to a door and the old man rapped on the glass. A muffled voice answered from inside. The old man showed me in, and there was his daughter standing in the center of the winter balcony, facing us, with her back to the colored panes. We were halfway across the room before she left the balcony and came forward to meet us. Reaching out through space she offered me her hand and thanked me for my visit. Backed against the darkest wall of the room was a small open piano. Its big yellowish smile looked innocent.

She apologized for not being able to leave the house and, pointing to the balcony, said:

“He’s my only friend.”

I indicated the piano and asked:

“How about this sweet soul? Isn’t he your friend, too?”

We were lowering ourselves into chairs at the foot of her bed. I had time to notice many small paintings of flowers, all hung at the same height, along the four walls, as though parts of a frieze. The smile she had abandoned in the middle of her face was as innocent as the piano’s, but her faded blonde hair and wispy figure also seemed to have been abandoned long ago. She was starting to explain why the piano wasn’t as close a friend as the balcony when the old man left the room almost on tiptoes. She went on saying:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piano Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piano Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piano Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.