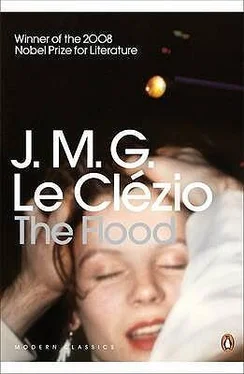

Jean-Marie Le Clézio - The Flood

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jean-Marie Le Clézio - The Flood» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Penguin Classics, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Flood

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Flood: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Flood»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Flood — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Flood», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Soon Besson found himself stretched out on the grass like a dozing giant who has been tied up, while asleep, by an army of little dwarfs. These Lilliputian creatures had driven pegs into the ground and then attached his hair to them with lengths of spider’s thread. His clothes had been sewn down, his hands and feet were covered with a fine-meshed, almost invisible network of creepers. That was it, he had been made one with the grass he lay on, they had taken him by surprise, he was a prisoner of the stubble and brushwood. Above him the sky stretched, pale and unfathomable, so vast that it was as though it did not really exist. Far up in the empyraean light swarmed and dazzled, streaming out on the sun’s right hand.

Little by little, Besson realized his position. He was pegged out as an offering on some high plateau, spreadeagled over the naked dome of the world in preparation for an incomprehensible sacrifice. Even from the depths of that tenderly pellucid sky the threat of death could materialize. There was no sure protection, nothing to cover him. Man’s flesh was frail, a touch could shiver his bones, he was exposed to endless unknown dangers. Stars, dead planets, meteorites — at any moment one of these could slam through the violet barrier of the atmosphere into the earth’s crust, digging a crater anything up to four hundred miles in diameter. Between him, Besson, and the freezing vertiginous nothingness of outer space, where suns exploded instantaneously, like bombs, what protection was there save this curtain of tulle, this scanty phosphorescent veil, this thin and all-too-penetrable envelope which did not even conceal him from view? A cold and comet-like frisson seemed to flash down from the clouds, entering Besson’s body by way of his navel. In broad daylight — despite the sun and the scent of pollen and these semi-reassuring noises — the cold breath of eternity spread through Besson’s guts as he lay there on the ground.

Some time later a white bird began to wheel around, far overhead: Besson watched its movements, the tight circles it described in the boundless air, with scarcely a flicker of his own eyes. The bird did not really use its wings at all, simply spread them wide and sailed down in a long planing glide, banking on air-currents, turning incessantly, round and round, so far up in the sky that its movements seemed reduced to immobility. It revolved about an invisible axis right over Besson’s head, constantly turning back on itself, following its previous track, dipping, rising, pivoting in the calm and silent void. Sometimes — whether on account of an air-pocket, or because it felt its balance in some way disturbed — it would flap its great soft wings, for a moment or two; but then it would set course once more, gliding, banking, turning, as though coming down an invisible staircase with no apparent bottom to it. Besson watched the bird with passionate absorption: he felt that its flight should go on for ever. From where he lay, on his patch of grass, he could not make out any details of the creature’s body: he could not isolate its head or its talons or the brown patches (if there were any) on its feathers. It could have been anything — seagull, sparrow-hawk, falcon, buzzard. Or an eagle, perhaps, an eagle that had flown down from the nearby mountains, and was now using those cruel eyes to spy out the victim on which it would shortly drop like a stone. It was impossible to tell which it was.

The bird continued to circle round, with a kind of stubborn violence. But all one could see of it was the cross formed by its body and outspread wings, poised aloft while the earth turned slowly under it. A sign indeed, a living emblem hung in that white abyss of sky, its progress stiffly majestic, rigid with hatred. The bird was the only image of activity throughout this whole enormous void: it was monarch of all it surveyed. As far as the eye could reach, on every side, nothing else existed. It hung there, supported by the density of the atmosphere, as one might imagine death — opening and shutting its snow-white calyx, or gathering its strength in preparation for the struggle against mankind. Its light, buoyant body exulted with joy, faint breezes ruffled its white plumage, and the light played over it from all sides, rendered it diaphanous, a mere drop of glass and vapour with blurring, crumbling outlines. It was flying, it would go on flying for ever. It belonged to the range of gaseous matter, and without the slightest doubt would never be able to return to earth. It would have to go on circling in the upper air, describing one circle after another, until the moment came when it reached exhaustion-point and gently evaporated into nothingness. It no longer breathed, it was in all likelihood no longer alive — or else had entered upon eternal life: volplaning, glittering in the azure void, forthright, concealing nothing, casting its terrible cruciform shadow on the ground, three yards from wing-tip to wing-tip, gliding in blank and solitary splendour, nothing now but the living, breathing spirit of flight, unable to give up. Intoxicated by its own perfect circles, hunger and fear all forgotten, having quit the world’s heights and crevasses centuries since. Lost, dumb, a sacrifice to the horizontal infinite; airborne. Airborne.

When Besson could no longer see the bird, he got up and made his way back down the path. At the foot of the hills lay the sea, under a blanket of mist. The sun had almost reached its zenith, and the wind had fallen. The chill in the air slowly turned to heat, drying off the rocks and forming dust in every cranny. Cars came tearing full pelt along the highway; the roar of their engines set Besson’s teeth on edge.

He set off along the shoulder of the road again, till he reached a clump of houses. The cars slowed down here, because of traffic lights. A little way off the highway Besson saw a square, with old men sitting on benches. In the middle of the square a jet-hose was spitting over a patch of green lawn, and pigeons swarmed everywhere. The sidewalks were also occupied by dogs, and cats with raw scabs on their backs, and sparrows. The houses were ugly and decrepit, with barred shutters. At a pinch, he thought, one could live here, too: marry, and have children, and call them names like André or Mireille. Twice a week the town hall was turned into a cinema: there were the posters on the walls— The Plainsman, The Crook who Defied Scotland Yard . The tobacconist’s name was Giugi; the doctor was called Bonnard, and the local lady of easy virtue Marie de Cavalous. From time to time there was a robbery, or some other crime. The village idiot was the deputy mayor’s illegitimate son. None of this mattered very much.

Everyone stared at Besson as he went by. He stopped at a bar and ordered a glass of lemonade over the counter, staring with great concentration at the yellow plastic surfaces and the chromium plating on the coffee-machine. At the far end of the room a juke-box started up: a raucous woman’s voice, supported by chorus and rhythm group, singing a mutedly vibrant number that went:

C’est bien la plus la

C’est bien la plus la

C’est bien la plus belle

Celle qu’on appelle la

Celle qu’on appelle la

Celle qu’on appelle la belle

La belle Isabelle

Besson drank his lemonade and paid for it. Then he stayed for a moment with his elbows on the counter, staring out at the street. Flies were busily sipping at the spilt water on the tables. Down the far end of the bar someone sneezed twice, and blew his nose.

Besson walked on out of the village. He had hardly seen anyone there.

Half a mile or so further on he went over a level-crossing and took a road that led down to the beach. The whole site was dotted with huts, shut up now, where they sold ice-cream, and peanuts during the summer. There were one or two notice-boards, too, which said things like CAMPING SITE or THIS WAY TO THE SEA or ALTITUDE ZERO or FIESTA BEACH. Besson stopped for a moment to look at the beach, and the headlands that enclosed it on either side of the horizon. The long stretch of shingle was deserted; incoming tides had forced it up into a high ridge. To the left, some way off, there was a concrete jetty, with groups of anglers dotted along it. To the right, in the distance again, there was what looked like a sewage dump. It was in this direction that Besson now proceeded, stumbling along over the warm shingle, breathing in the tangy smell of the sea. Everything had become white, grey, or pink, except the sea, which was so blue it hurt one’s eyes to look at it. Occasional patches of crude oil glistened in the sunlight, and along the tide-mark, small heaps of vitreous blubber, lay a number of stranded jellyfish.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Flood»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Flood» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Flood» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.