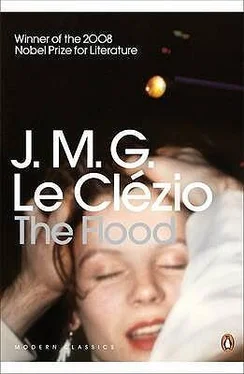

Jean-Marie Le Clézio - The Flood

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jean-Marie Le Clézio - The Flood» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Penguin Classics, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Flood

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Flood: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Flood»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Flood — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Flood», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

By the time that Besson’s parents — alerted by the unmistakable crackling roar of the fire — came rushing into his room, flames were already licking over the bedclothes and up the wallpaper. There were shouts of alarm, footsteps hurrying across the floor. At this point Besson picked up his beach-bag and went, without one backward glance. In order to shake off the effects of that blinding heat, though, he had to sit down for a bit on a park bench, and smoke a cigarette.

When evening came, François Besson strolled through the canyon-like streets of the town. He saw men and women walking along the pavement, in couples, and gangs of children playing war games. Everyone was busy, they all had a warm, comfortable lodging to bury themselves in for the night. In each cell of those vast apartment blocks some heavy-bosomed housewife would be preparing the evening meal, and the brightly-lit kitchens would be redolent of leek-and-potato soup, fish-fries, apple fritters, a peaceful domestic aroma. People smiled as they passed one another: sometimes they called out a greeting, and when they talked it was in very loud voices. But none of this was for Besson. He walked on in silence, and passers-by either stared very hard at him, eyes narrowed, or else gave him a furtive glance and looked away again. Workmen and builders’ labourers stood about in the bars, drinking glasses of beer, eyes fixed on the television set quacking away in its corner. From somewhere a long way off came the faint sound of church bells ringing. Shop-windows began to light up, one after the other, and the neon signs embarked on their endless, endlessly repeated, flashing messages. Above one travel agency words flickered along a broad strip dotted with electric light bulbs. Besson read: STOP PRESS NEWS PLANE CRASH AT TEL-AVIV EIGHTEEN DEAD. A little further on he saw some pigeons perched on the letters of a neon-sign, just under the roof-guttering, waddling about and warming their feet. Beyond them he came on an old man leaning against the wall, playing ‘Mon ami Pierrot’ on a tin whistle, with an upturned hat at his feet. Behind the glass of a display case there were photographs of babies and small kneeling girls. Their mouths gaped open in fixed smiles, their eyes shone as though wax-polished. Everywhere men had left their mark: house-doors, window-sills, sidewalk, sky and trees, dogs’ backs, rusty iron street-signs — all bore their names and addresses. Nowhere could one get away from them. These vertical mountains, all honeycombed with rectangular holes, were full of spying eyes, mouths that gossiped when they weren’t eating, well-washed skin, well-combed hair, bitten fingernails, bodies swathed in wool or nylon. No other landscape had ever existed remotely like this one: such a limited area had never contained so many impenetrable cavities, so many defiles and moraines. No mountain could be as high as these buildings, no valley as deep and narrow as the streets outside them. Some fearful force had carved out these contours, it had taken a hideous and incomparable explosion of violence to erect these monuments, drain the soil, level out the rough places, crush the rocks, plan, dig, manipulate the elements, organize space, and make the little streams run meekly obedient to the will of authority. The houses had their roots dug deep into the rock, and clung to this conquered territory with a kind of ferocious hatred.

Besson walked humbly through these streets in which he had no part, moving aside to let the victors have free passage — the round-shouldered women, the crop-haired children, the men on their way home from work. When he wanted to cross the street he waited until there was a gap in the traffic, no more rubber tyres hissing past. He ducked his head and hunched himself defensively against the assaults of lights and noises and frantic scrambling movement. Lights winked on and off everywhere, at the summits of steel pylons, in the streets, out at sea: red and yellow points riveted into place, then wiped out, replaced by others. It was like being shut under a gigantic lid, made of lead and resting firmly on the ground, a lid that pressed down with its whole weight on one’s skin and eardrums and diaphragm and neck. The cold air had become a kind of liquid substance; people were mostly staying indoors now. Very soon Besson had to stop through sheer fatigue. It was completely dark now, and indeed time for dinner. With the money he had left Besson decided to go and eat in the self-service restaurant.

Sitting at a black table with smears of sauce on it, opposite a fat and ugly old woman whose small mean eyes watched his every move, Besson did his best to swallow some food. On his tray he had collected the following: a plate of sliced tomatoes with chopped parsley on them, an egg mayonnaise, a dish containing one portion of roast chicken (leg) and fried potatoes, a glass of water, a yoghourt, three sachets of granulated sugar, a hunk of stale bread, knife, fork, soup-spoon, coffee-spoon, a thin paper napkin with Bon Appétit! or some such legend inscribed on it, and a piece of paper which read:

ROYAL SELF-SERVICE RESTAURANT

80

80

120

120

550

550

80

80

15

15

20

20

= = 865

= = 865

Besson tried to swallow the tomatoes and cut up the chicken. But the food was hostile, it slid about on the plate, refused to be chewed or swallowed. Water dribbled over his chin when he drank, as though some joker had drilled a hole in the glass. The egg slipped about in its mayonnaise, and the chicken wouldn’t keep still either. It was all somehow quite repulsive — ill-cooked flesh, dead roots, a taste of earth, perhaps even of excrement. Besson attempted to chew this stuff. He swallowed lumps of dry meat and slices of egg-white that smelt of sulphur. He dribbled, struggled, messed up his hands and clothes, dropped first his knife then his spoon. Eating, it seemed, was impossible. And on top of everything else there was the old woman, taking in every detail of his defeat with an ironic eye. Besson abandoned solid food and set about the yoghourt. But this turned out very little better. He managed to get the little spoon to his mouth, but the viscous substance acquired a life of its own: it tried to get away from him, it ran under his tongue, slipped past the barrier of the uvula, came back down his nasal passages. Bent over the pot of yoghourt, in a mere simulacrum of the nutritional process, Besson felt as though he were a small child again. The hard stare of the old woman and the inscrutable faces of other diners scattered through the restaurant all showed him his own reflection, as clearly as so many mirrors: a tenuous, cloudy object, curled up on itself, a phantom, or a foetus still covered with glaireous matter, something that scarcely belonged to the human species.

So there it was, the group rejected him spontaneously, like any freak. Having robbed him of his most intimate thoughts and actions, they were now about to strip him of his body, too, and condemn him to the void. This was the message to be read on the sneering faces around him, the thick hands so competent at dismembering roast chicken, the mouths with their rows of sharp teeth that could chew, salivate, reduce to pulp, the coiled and deep-hidden organs that wanted to transform everything into scarlet blood, its regular pulsing flow pricking out under the skin like millions of tiny needles.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Flood»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Flood» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Flood» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.