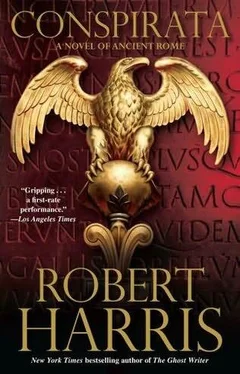

Robert Harris - Lustrum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Harris - Lustrum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lustrum

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lustrum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lustrum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lustrum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lustrum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'No,' said Cato, shaking his head, 'no, you are wrong. Pompey has subjugated peoples with whom we had no quarrel, he has entered lands in which we have no business, and he has brought home wealth we have not earned. He is going to ruin us. It is my duty to oppose him.'

From this impasse, not even Cicero's agile brain could devise a means of escape. He went to see Pompey later that afternoon to report his failure, and found him in semi-darkness, brooding over the model of his theatre. The meeting was too short even for me to take a note. Pompey listened to the news, grunted, and as we were leaving called after Cicero, 'I want Hybrida recalled from Macedonia at once.'

This threatened Cicero with a serious personal crisis, for he was being hard-pressed by the moneylenders. Not only did he still owe a sizeable sum for the house on the Palatine; he had also bought several new properties, and if Hybrida stopped sending him a share of his spoils in Macedonia – which he had at last begun to do – he would be seriously embarrassed. His solution was to arrange for Quintus's term as governor of Asia to be extended for another year. He was then able to draw from the treasury the funds that should have gone to defray his brother's expenses (he had full power of attorney) and hand the whole lot over to his creditors to keep them quiet. 'Now don't give me one of your reproachful looks, Tiro,' he warned me, as we came out of the Temple of Saturn with a treasury bill for half a million sesterces safely stowed in my document case. 'He wouldn't even be a governor if it weren't for me, and besides, I shall pay him back.' Even so, I felt very sorry for Quintus, who was not enjoying his time in that vast, alien and disparate province and was very homesick.

Over the next few months, everything played out as Cicero had predicted. An alliance of Crassus, Lucullus, Cato and Celer blocked Pompey's legislation in the senate, and Pompey duly turned to a friendly tribune named Fulvius, who laid a new land bill before the popular assembly. Celer then attacked the proposal with such violence that Fulvius had him committed to prison. The consul responded by having the back wall of the gaol dismantled so that he could continue to denounce the measure from his cell. This display of resolution so delighted the people, and discredited Fulvius, that Pompey actually abandoned the bill. Cato then alienated the Order of Knights entirely from the senate by stripping them of jury immunity and also refusing to cancel the debts many had incurred by unwise financial speculation in the East. In both of these actions he was absolutely right morally whilst being at the same time utterly wrong politically.

Throughout all this, Cicero made few public speeches, confining himself entirely to his legal practice. He was very lonely without Quintus and Atticus, and I often caught him sighing and muttering to himself when he thought he was alone. He slept badly, waking in the middle of the night and lying there with his mind churning, unable to nod off again until dawn. He confided to me that during these intervals, for the first time in his life, he was plagued with thoughts of death, as men of his age – he was forty-six – frequently are. 'I am so utterly forsaken,' he wrote to Atticus, 'that my only moments of relaxation are those I spend with my wife, my little daughter and my darling Marcus. My worldly, meretricious friendships may make a fine show in public, but in the home they are barren things. My house is crammed of a morning, I go down to the forum surrounded by droves of friends, but in all the crowds I cannot find one person with whom I can exchange an unguarded joke or let out a private sigh.'

Although he was too proud to admit it, the spectre of Clodius also disturbed his rest. At the beginning of the new session, a tribune by the name of Herennius introduced a bill on the floor of the senate proposing that the Roman people should meet on the Field of Mars and vote on whether or not Clodius should be permitted to become a pleb. That did not alarm Cicero: he knew the measure would swiftly be vetoed by the other tribunes. What did disturb him was that Celer spoke up in support of it, and after the senate was adjourned he sought him out.

'I thought you were opposed to Clodius transferring to the plebs?'

'I am, but Clodia nags me morning and night about it. The measure won't pass in any case, so I hope this will give me a few weeks' peace. Don't worry,' he added quietly. 'If ever it comes to a serious fight, I shall say what I really feel.'

This answer did not entirely reassure Cicero, and he cast about for some means of binding Celer to him more closely. As it happened, a crisis was developing in Further Gaul. A huge number of Germans – one hundred and twenty thousand, it was reported – had crossed the Rhine and settled on the lands of the Helvetii, a warlike tribe, whose response was to move westwards in their turn, into the interior of Gaul, looking for fresh territory. This situation was deeply troubling to the senate, and it was decided that the consuls should at once draw lots for the province of Further Gaul, in case military action proved necessary. It promised to be a glittering command, full of opportunites for wealth and glory. Because both consuls were competitors for the prize – Pompey's clown, Afranius, was Celer's colleague – it fell to Cicero to conduct the ballot, and while I will not go so far as to say he rigged it – as he had once before for Celer – nevertheless it was Celer who drew the winning token. He quickly repaid the debt. A few weeks later, when Clodius returned to Rome from Sicily after his quaestorship was over, and stood up in the senate to demand the right to transfer to the plebs, it was Celer who was the most violent in his opposition.

'You were born a patrician,' he declared, 'and if you reject your birthright you will destroy the very codes of blood and family and tradition on which this republic rests!'

I was standing at the door of the senate when Celer made his about-turn, and the expression on Clodius's face was one of total surprise and horror. 'I may have been born a patrician,' he protested, 'but I do not wish to die one.'

'You most assuredly will die a patrician,' retorted Celer, 'and if you continue on your present course, I tell you frankly, that inevitability will befall you sooner rather than later.'

The senate murmured with astonishment at this threat, and although Clodius tried to brush it off, he must have known that his chances of becoming a pleb, and thus a tribune, lay at that moment in ruins.

Cicero was delighted. He lost all fear of Clodius and from then on foolishly took every opportunity to taunt him and jeer at him. I remember in particular an occasion not long after this when he and Clodius found themselves walking together into the forum to introduce candidates at election time. Unwisely, for plenty around them were listening, Clodius took the opportunity to boast that he had now taken over from Cicero as the patron of the Sicilians, and henceforth would be providing them with seats at the Games. 'I don't believe you were ever in a position to do that,' he sneered.

'I was not,' conceded Cicero.

'Mind you, space is hard to come by. Even my sister, as consul's wife, says she can only give me one foot.'

'Well, I wouldn't grumble about one foot in your sister's case,' replied Cicero. 'You can always hoist the other.'

I had never before heard Cicero make a dirty joke, and afterwards he rather regretted it as being 'unconsular'. Still, it was worth it at the time for the roars of laughter it elicited from everyone standing around, and also for the effect it had on Clodius, who turned a fine shade of senatorial purple. The remark became famous and was repeated all over the city, although mercifully no one had the courage to relay it back to Celer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lustrum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lustrum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lustrum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.