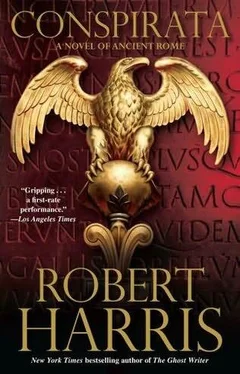

Robert Harris - Lustrum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Harris - Lustrum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lustrum

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lustrum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lustrum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lustrum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lustrum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Excellent advice!' exclaimed Pompey. 'Four it will be,' and he set them down in a row, to the applause of his audience. 'We shall decide which gods they are to be dedicated to later. Well?' he said to Cicero, gesturing to the model. 'What do you think?'

Cicero peered down at the elaborate construction. 'Most impressive. What is it? A palace?'

'A theatre, with seating for ten thousand. Here will be public gardens, surrounded by a portico. And here temples.' He turned to one of the men behind him, who I realised must be architects. 'Remind me again: how big is it going to be?'

'The whole construction will extend for a quarter of a mile, Excellency.'

Pompey grinned and rubbed his hands. 'A building a quarter of a mile in length! Imagine it!'

'And where is it to be built?' asked Cicero.

'On the Field of Mars.'

'But where will the people vote?'

'Oh, here somewhere,' said Pompey, waving his hand vaguely, 'or down here by the river. There'll still be plenty of room. Take it away, gentlemen,' he ordered, 'take it away and start digging the foundations, and don't worry about the cost.'

After they had gone, Cicero said, 'I don't wish to sound pessimistic, Pompey, but I fear you may have trouble over this with the censors.'

'Why?'

'They've always forbidden the building of a permanent theatre in Rome, on moral grounds.'

'I've thought of that. I shall tell them I'm building a shrine to Venus. It will be incorporated into the stage somehow – these architects know what they're doing.'

'You think the censors will believe you?'

'Why wouldn't they?'

'A shrine to Venus a quarter of a mile long? They might think you're taking your piety to extreme lengths.'

But Pompey was in no mood for teasing, especially not by Cicero. All at once his generous mouth shrank into a pout. His lips quivered. He was famous for his short temper, and for the first time I witnessed just how quickly he could lose it. 'This city!' he cried. 'It's so full of little men – just jealous little men! Here I am, proposing to donate to the Roman people the most marvellous building in the history of the world, and what thanks do I receive? None. None! ' He kicked over one of the trestles. I was reminded of little Marcus in his nursery after he had been made to put away his games. 'And speaking of little men,' he said menacingly, 'why hasn't the senate given me any of the legislation I asked for? Where's the bill to ratify my settlements in the East? And the land for my veterans – what's become of that?'

'These things take time…'

'I thought we had an understanding: I would support you in the matter of Hybrida, and you would secure my legislation for me in the senate. Well, I've done my part. Where's yours?'

'It is not an easy matter. I can hardly carry these bills on my own. I'm only one of six hundred senators, and unfortunately you have plenty of opponents among the rest.'

'Who? Name them!'

'You know who they are better than I. Celer won't forgive you for divorcing his sister. Lucullus is still resentful that you took over his command in the East. Crassus has always been your rival. Cato feels that you act like a king-'

'Cato! Don't mention that man's name in my presence! It's entirely thanks to Cato that I have no wife!' The roar of Pompey's voice was carrying through the house, and I noticed that some of his attendants had crept up to the door and were standing watching. 'I put off raising this with you until after my triumph, in the hope that you'd have made some progress. But now I am back in Rome and I demand that I am given the respect I'm due! Do you hear me? I demand it!'

'Of course I hear you. I should imagine the dead can hear you. And I shall endeavour to serve your interests, as your friend, as I always have.'

'Always? Are you sure of that?'

'Name me one occasion when I was not loyal to your interests.'

'What about Catilina? You could have brought me home then to defend the republic.'

'And you should thank me I didn't, for I spared you the odium of shedding Roman blood.'

'I could have dealt with him like that!' Pompey snapped his fingers.

'But only after he had murdered the entire leadership of the senate, including me. Or perhaps you would have preferred that?'

'Of course not.'

'Because you know that was his intention? We found weapons stored within the city for that very purpose.'

Pompey glared at him, and this time Cicero stared him out: indeed, it was Pompey who turned away first. 'Well, I know nothing about any weapons,' he muttered. 'I can't argue with you, Cicero. I never could. You've always been too nimble-witted for me. The truth is, I'm more used to army life than politics.' He forced a smile. 'I suppose I must learn that I can no longer simply issue a command and expect the world to obey it. “Let arms to toga yield, laurels to words” – isn't that your line? “O, happy Rome, born in my consulship” – there, you see? There's another. You can tell what a student I have become of your work.'

Pompey was not normally a man for poetry, and it was immediately clear to me that the fact that he could recite these lines from Cicero's consular epic – which had just started to be read all over Rome – was proof that he was dangerously jealous. Still, he somehow managed to bring himself to pat Cicero on the arm, and his courtiers exhaled with relief. They drifted away from the entrance, and gradually the sounds of the house resumed, whereupon Pompey – whose bonhomie could be as abrupt and disconcerting as his rages – suddenly announced that they should drink some wine. It was brought in by a very beautiful woman, whose name, I discovered afterwards, was Flora. She was one of the most famous courtesans in Rome and was living under Pompey's roof while he was between wives. She always wore a scarf around her neck, to conceal, she said, the bite marks Pompey inflicted when he was making love. She poured the wine demurely and then withdrew, while Pompey showed us Alexander's cloak, which had, he said, been found in Mithradates's private apartments. It looked very new to me, and I could see that Cicero was having difficulty keeping a straight face. 'Imagine,' he said in a hushed voice, feeling the material with great reverence, 'three hundred years old, and yet it looks as though it was made less than a decade ago.'

'It has magical properties,' said Pompey. 'As long as I keep it by me, I am told no harm can befall me.' He became very serious as he showed Cicero to the door. 'Speak to Celer, will you, and the others, on my behalf? I promised my veterans that I would give them land, and Pompey the Great can't be seen to go back on his word.'

'I'll do everything I can.'

'I'd prefer to work through the senate, but if I have to find my friends elsewhere, I shall. You can tell them I said that.'

As we walked home, Cicero said, 'Did you hear him? “I know nothing about any weapons”! Our Pharaoh may be a great general, but he is a terrible liar.'

'What are you going to do?'

'What else can I do? Support him, of course. I don't like it when he says he might try to find his friends elsewhere. At all costs I must try to keep him out of the arms of Caesar.'

And so Cicero put aside his distaste and his suspicions and did the rounds on Pompey's behalf, just as he had done years before when he was merely a rising senator. It was yet another lesson to me in politics – an occupation that, if it is to be pursued successfully, demands the most extraordinary reserves of self-discipline, a quality that the naive often mistake for hypocrisy.

First, Cicero invited Lucullus to dinner and spent several fruitless hours trying to persuade him to abandon his opposition to Pompey's bills; but Lucullus would never forgive The Pharaoh for taking all the credit for the defeat of Mithradates, and flatly refused to co-operate. Next, Cicero tried Hortensius, and received the same response. He even went to see Crassus, who, despite clearly wishing to destroy his visitor, nevertheless received him very civilly. He sat back in his chair with the tips of his fingers pressed together and his eyes half closed, listening to Cicero's appeal and relishing every word.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lustrum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lustrum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lustrum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.