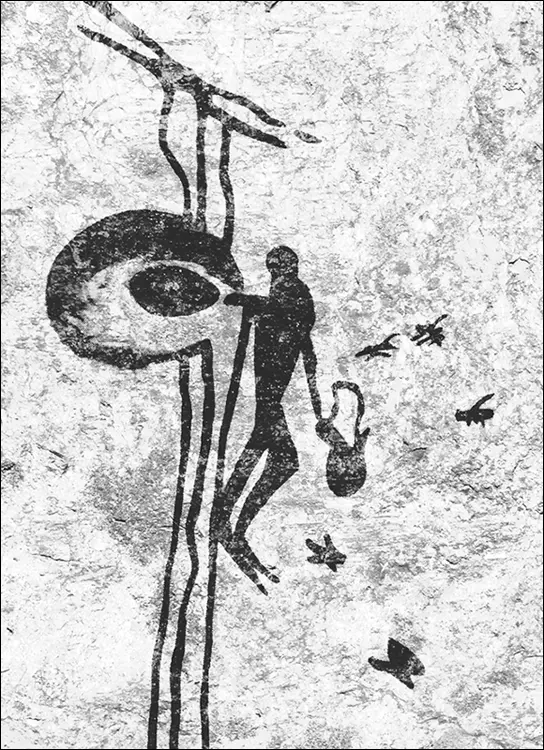

BEE HUNTERS, GATHERERS, AND CULTIVATORS

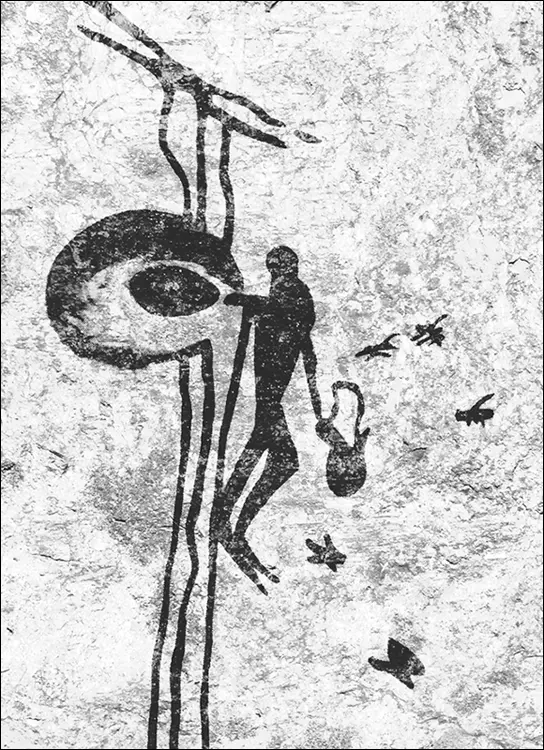

An early cave painting in Biscorp, Spain, circa 6000 BC, shows early Spaniards hunting for and harvesting wild honey (see the accompanying figure). In centuries past, honey was a treasured and sacred commodity. It was used as money and praised as the nectar of the gods. Methods of beekeeping remained relatively unchanged until 1852 with the introduction of today’s “modern” removable-frame hive, also known as the Langstroth hive. (See Chapter 4for more information about Langstroth and other kinds of beehives.)

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

Improving your health: Bee therapies and stress relief

Although I can’t point to any scientific studies to confirm it, I honestly believe that tending honey bees reduces stress. Working with my bees is so calming and almost magical. I am at one with nature, and whatever problems may have been on my mind tend to evaporate. There’s something about being out there on a lovely warm day, the intense focus of exploring the wonders of the hive, and hearing that gentle hum of contented bees — it instantly puts me at ease, melting away whatever day-to-day stresses I may find creeping into my life.

Any health food store proprietor can tell you the benefits of the bees’ products. Honey, pollen, royal jelly, and propolis have been a part of healthful remedies for centuries. Honey and propolis have significant antibacterial qualities. Royal jelly is loaded with B vitamins and is widely used around the world as a dietary and fertility stimulant. Pollen is high in protein and can be used as a homeopathic remedy for seasonal pollen allergies (see the sidebar “Bee pollen, honey, and allergy relief” in this chapter).

BEE POLLEN, HONEY, AND ALLERGY RELIEF

Pollen is one of the richest and purest of natural foods, consisting of up to 35 percent protein and 10 percent sugars, carbohydrates, enzymes, minerals, and vitamins A (carotenes), B1 (thiamin), B2 (riboflavin), B3 (nicotinic acid), B5 (panothenic acid), C (ascorbic acid), H (biotin), and R (rutine).

Here’s the really neat part: Ingesting small amounts of pollen every day can actually help reduce the symptoms of pollen-related allergies — sort of a homeopathic way of inoculating yourself. The key is to use pollen that is harvested from your general region.

Of course you can harvest pollen from your own bees and sprinkle a small amount on your breakfast cereal or in yogurt (as you might do with wheat germ). But you don’t really need to harvest the pollen itself. That’s because raw, natural honey contains bits of pollen. Pollen’s benefits are realized every time you take a tablespoon of honey. Eating local honey every day can relieve the symptoms of pollen-related allergies if the honey is harvested from within a 50-mile radius of where you live or from an area where the vegetation is similar to what grows in your community. The best part if you have your own bees, allergy relief is only a sweet tablespoon away!

Apitherapy is the use of bee products for treating health disorders. Even the bees’ venom plays an important role here — in bee-sting therapy. Venom is administered with success to patients who suffer from arthritis and other inflammatory/medical conditions. This entire area has become a science in itself and has been practiced for thousands of years in Asia, Africa, and Europe. An interesting book on apitherapy is Bee Products — Properties, Applications and Apitherapy: Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Tel Aviv, Israel, May 26–30, 1996, published by Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Determining Your Beekeeping Potential

How do you know whether you’d make a good beekeeper? Is beekeeping the right hobby for you? Here are a few things worth considering as you ponder these issues.

Environmental considerations

Unless you live on a glacier or on the frozen tundra of Siberia, you probably can keep bees. Bees are remarkable creatures that do just fine in a wide range of climates. Beekeepers can be found in areas with long, cold winters; in tropical rain forests; and in nearly every geographic region in between. If flowers bloom in your part of the world, you can keep bees.

How about space requirements? You don’t need much. I know many beekeepers in the heart of Manhattan. They have a hive or two on their rooftops or terraces. Keep in mind that bees travel two to three miles from their hive to gather pollen and nectar. They’ll forage an area as large as 8,500 acres. So the only space that you need is enough to accommodate the hive itself.

See Chapter 3for more specific information on where to locate your bees, in either urban or suburban situations.

Zoning and legal restrictions

Most communities are quite tolerant of beekeepers, but some have local ordinances that prohibit beekeeping or restrict the number of hives you can have. Some communities let you keep bees but ask that you register your hives with local authorities. Check with local bee clubs, your town hall, your local zoning board, or your state’s Department of Agriculture (bee/pollinating insects division) to find out about what’s okay in your community.

Obviously you want to practice a good-neighbor policy so folks in your community don’t feel threatened by your unique new hobby. See Chapter 3for more information on the kinds of things you can do to prevent neighbors from getting nervous.

What does it cost to become a beekeeper? All in all, beekeeping isn’t a very expensive hobby. You can figure on investing about $200 to $400 for a start-up hive kit, equipment, and tools — less if you build your own hive from scratch (find out how to do it in my book, Building Beehives For Dummies, published by Wiley). You’ll spend around $175 or more for a package of bees and queen. For the most part, these are one-time expenses. Keep in mind, however, the potential for a return on this investment. Each of your hives can give you 40 to 70 pounds of honey every year. At around $8 per pound (a fair going price for all-natural, raw honey), that should give you an income of $320 to $560 per hive! Not bad, huh?

See Chapter 5for a detailed listing of the equipment you’ll need.

How many hives do you need?

Most beekeepers start out with one hive. And that’s probably a good way to start your first season. But most beekeepers wind up getting a second hive in short order. Why? For one, it’s twice as much fun! Another more practical reason for having a second hive is that recognizing normal and abnormal situations is easier when you have two colonies to compare. In addition, a second hive enables you to borrow bees/honey from a stronger, larger colony to supplement one that needs a little help. My advice? Start with one hive during your first season until you get the hang of things and then by all means consider expanding in your second season.

What kind of honey bees should you raise?

The honey bee most frequently raised by beekeepers in the United States today is European in origin and has the scientific name Apis mellifera.

Of this species, one of the most popular variety is the so-called Italian honey bee. These bees are docile, hearty, and good honey producers. They are a good choice for the new beekeeper. But there are notable others to consider. It can be great fun to to experiment with different varieties. See Chapter 6for more information about different varieties of honey bees.

Читать дальше