1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...20 Under proposed guidelines, the use of some medications and chemical treatments is likely to be okay. To run a certified organic beekeeping operation, be prepared to take on a lot of work and make a sobering investment. Not too practical for the average backyard beekeeper. For the latest status of the new organic beekeeping regulations (known as Organic Apiculture Practice Standard, NOP-12-0063), visit the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at www.reginfo.gov .

Okay. Here’s my take on all of this. I don’t personally follow any one of the medicated, natural, or organic approaches exclusively. In my view, there are no absolutes. I have no need to be certified as organic, so I choose not to go down that path. Generally speaking, I do not use chemicals “just in case” I may have a problem with pests. Nor do I typically medicate my bees as a preventive measure, but only when absolutely necessary, and only when other nonchemical options have not been effective. The same is true at home. I certainly don’t take antibiotics whenever I feel sick or if I think I might get sick. But rest assured, if I came down with bacterial pneumonia, I would likely be asking my doc for antibiotics. And I certainly vaccinate my sweet golden retriever to keep her free of distemper. So my personal approach does not eliminate any use of medications, but rather follows a thoughtful, responsible approach that aspires to be as natural as possible. Like me, you may want to make choices based on what feels right to you.

In this edition, I have included lots of information that highlights alternative, more natural approaches to beekeeping than are found in books published in years past. Look for the All Natural icon to easily identify suggestions for those of you (like me) who are aspiring to minimize the use of medications and chemicals.

In this edition, I have included lots of information that highlights alternative, more natural approaches to beekeeping than are found in books published in years past. Look for the All Natural icon to easily identify suggestions for those of you (like me) who are aspiring to minimize the use of medications and chemicals.

Chapter 2

Getting to Know Your Honey Bees

IN THIS CHAPTER

Recognizing bee parts and what they do

Recognizing bee parts and what they do

Exploring how bees communicate with each other

Exploring how bees communicate with each other

Getting acquainted with the two female castes and the male

Getting acquainted with the two female castes and the male

Understanding the honey bee life cycle

Understanding the honey bee life cycle

Distinguishing the differences between honey bees and similar insects

Distinguishing the differences between honey bees and similar insects

My first introduction to life inside the honey bee hive occurred many years ago during a school assembly. I was about 10 years old. My classmates and I were shown a wonderful movie about the secret inner workings of the beehive. The film mesmerized me. I’d never seen anything so remarkable and fascinating. How could a bug be so smart and industrious? I couldn’t help being captivated by the bountiful honey bee. That brief childhood event planted a seed that blossomed into a treasured hobby decades later.

Anyone who knows even a little bit about the honey bee can’t help but be amazed, because far more goes on within the hive than most people can ever imagine: complex communication, social interactions, teamwork, unique jobs and responsibilities, food gathering, and the engineering of one of the most impressive living quarters found in nature. Whether you’re a newcomer or an old hand, you’ll have many opportunities to experience firsthand the miracle of beekeeping. Every time you visit your bees, you’ll see something new. But you’ll get far more out of your new hobby if you understand more about what you’re looking at. What are the physical components of the bee that enable it to do its job so effectively? What are those bees up to and why? What’s normal and what’s not normal? What is a honey bee, and what is an imposter? In this chapter, you take a peek within a typical colony of honey bees.

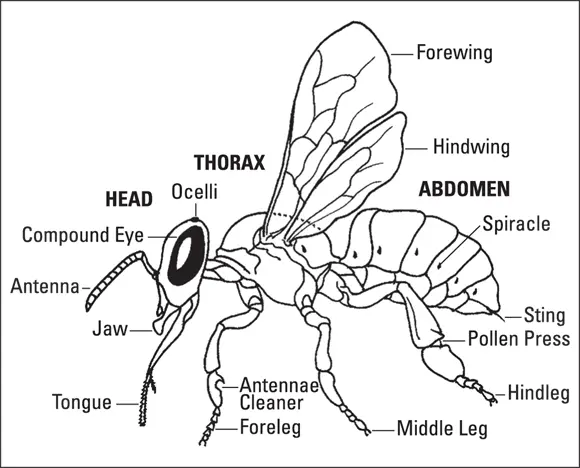

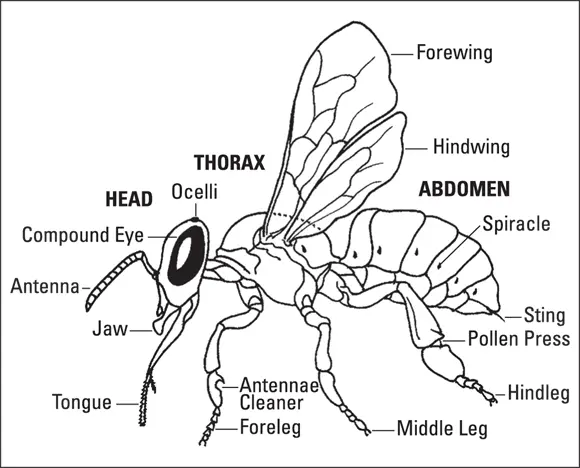

Everyone knows about at least one part of the honey bee’s anatomy: its stinger. But you’ll get more out of beekeeping if you understand a little bit about the other parts that make up the honey bee. I don’t go into this in textbook-detail — I just show you a few basic parts to help you understand what makes honey bees tick. Figure 2-1 shows the basic parts of the worker bee.

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 2-1:This is how a honey bee looks if you shave off all the hairs. Several important body features are labeled.

Like all insects, the honey bee’s skeleton is on the outside. This arrangement is called an exoskeleton. On the outside, nearly the entire bee is covered with branched hairs (like the needles on the branch of a spruce tree). Yes, the hairs help keep the bee body warm, but they also do much more. A bee can “feel” with these hairs, and the hairs serve the bee well when it comes to pollination because pollen sticks well to the branched hairs.

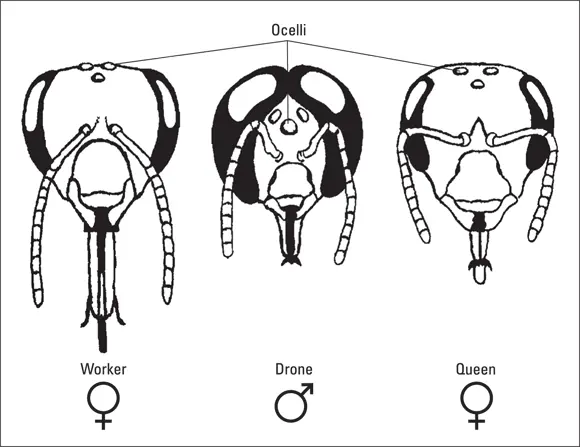

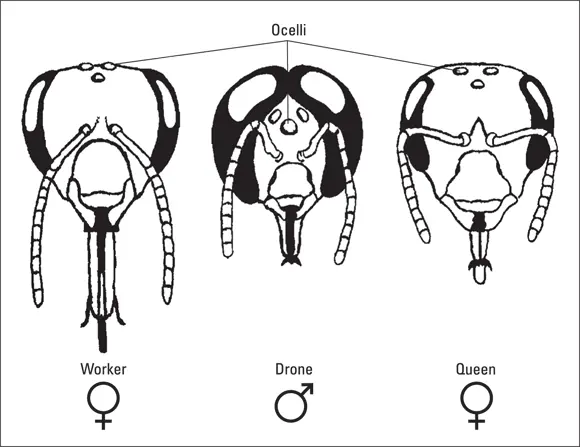

The honey bee’s head is flat and somewhat triangular in shape. Here’s where you find the bee’s brain and primary sensory organs (sight, feel, taste, and smell). It’s also where you find important glands that produce royal jelly and some of the various chemical pheromones used for communication. Figure 2-2 compares the heads of a worker, drone, and queen.

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 2-2:Comparing the heads of worker, drone, and queen bees. Note the worker bee’s extra-long proboscis and the drone’s huge, wraparound eyes.

Royal jelly is a substance secreted from glands in a worker bee’s head and is used as a food to feed brood.

The important parts of the bee’s head are its

Eyes: The head includes two large, compound eyes that are used for general-distance sight, and three small, simple eyes, called ocelli, which are used in the poor light conditions within the hive. Notice the three simple eyes (ocelli) on all three bee types Figure 2-2, while the huge, wraparound, compound eyes of the drone make him easy to identify. The queen’s eyes, are slightly smaller than the worker bee’s and much smaller than the drone’s.

Antennae: The honey bee has two elbowed antennae on the front of its face. Each antenna has thousands of tiny sensors that detect smell (like a nose does). The bee uses this sense of smell to identify flowers, water, the colony, and maybe even you! The antennae also, like the branched hairs mentioned earlier, feel, detect moisture, measure distance when bees fly, and help the bee detect up and down, among other functions.

Mouth parts: The bees’ mandibles (jaws) are used for feeding larvae, collecting pollen, manipulating wax, and carrying things.

Читать дальше

In this edition, I have included lots of information that highlights alternative, more natural approaches to beekeeping than are found in books published in years past. Look for the All Natural icon to easily identify suggestions for those of you (like me) who are aspiring to minimize the use of medications and chemicals.

In this edition, I have included lots of information that highlights alternative, more natural approaches to beekeeping than are found in books published in years past. Look for the All Natural icon to easily identify suggestions for those of you (like me) who are aspiring to minimize the use of medications and chemicals. Recognizing bee parts and what they do

Recognizing bee parts and what they do