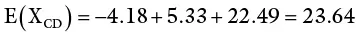

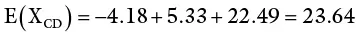

SCA is calculated as follows:

This is done for each combination and a plot of observed values versus expected values plotted. Because the values of SCA are subject to sampling error, the points on the plot do not lie on the diagonal. The distance from each point to the diagonal represents the SCA plus sampling error of the cross. Additional error would occur if the lines used in the cross are not highly inbred (error due to the sampling of genotypes from the lines).

Combining ability calculations are statistically robust, being based on first degree statistics (totals, means). No genetic assumptions are made about individuals. The concept is applicable to both self‐pollinated and cross‐pollinated species, for identifying desirable cross combinations of inbred lines to include in a hybrid program or for developing synthetic cultivars. It is used to predict the performance of hybrid populations of cross‐pollinated species, usually via a test cross or polycross. It should be pointed out that combining ability calculations are properly applied only in the context in which they were calculated. This is because GCA values are relative and depend upon the mean of the chosen parent materials in the crosses.

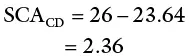

A typical ANOVA for combining ability analysis is as follows:

| Source |

df |

SS |

MS |

EMS |

| GCA |

p −1 |

S G |

M G |

σ 2 E+ σ 2 SCA+ σ 2 GCA |

| SCA |

p(p − 1)/2 |

S S |

M S |

σ 2 E+ σ 2 SCA |

| Error |

m |

S E |

M E |

σ 2 E |

The method used of a combining ability analysis depends on available data:

The method depends on available data:

Parents + F1 or F2 and reciprocal crosses (i.e. p2 combination).

Parents + F1 or F2, without reciprocals (i.e. ½ p(p + 1 combinations).

F1 + F2 + reciprocals, without parents and reciprocals (i.e. ½ p(p−1) combination.

Only F1 generations without parents, reciprocals (i.e. ½ p(p−1) combinations.

Artificial crossing or mating is a common activity in plant breeding programs for generating various levels of relatedness among the progenies that are produced. Mating in breeding has two primary purposes:

1 To generate information for the breeder to understand the genetic control or behavior of the trait of interest.

2 To generate a base population to initiate a breeding program.

The breeder influences the outcome of a mating by the choice of parents, the control over the frequency each parent is involved in mating, and the number of offspring per mating, among other ways. A mating may be as simple as a cross between two parents, to the more complex diallele mating.

These are reviewed here to give the student a basis for comparison with the random mating schemes to be presented.

Single cross = A × B → F1 (AB)

3‐way cross = (A × B) → F1 × C → (ABC)

Backcross = (A × B) → F1 × A → (BC1)

Double cross = (A × B) → FAB; (C × D) → FCD; FAB × FCD → (ABCD)

These crosses are relatively easy to genetically analyze. The breeder exercises significant control over the mating structure.

Mating designs for random mating populations

The term mating designis usually applied to schemes used by breeders and geneticists to impose random mating for a specific purpose. To use these designs, certain assumptions are made by the breeder:

The materials in the population have diploid behavior. However, polyploids that can exhibit disomic inheritance (alloploids) can be studied.

The genes controlling the trait of interest are independently distributed among the parents (i.e. uncorrelated gene distribution).

Absence of: non‐allelic interactions, reciprocal differences, multiple alleles at the loci controlling the trait, and GxE interactions.

Biparental mating (or pair crosses)

In this design, the breeder selects a large number of plants ( n ) at random and crosses them in pairs to produce ½ n full‐sib families. The biparental (BIP) is the simplest of the mating designs. If r plants per progeny family are evaluated, the variation within and between families may be analyzed as follows:

| Source |

df |

MS |

EMS |

| Between families |

(½ n) − 1 |

MS 1 |

σ 2w + rσ 2b |

| Within families |

½ n(r − 1) |

MS 2 |

σ 2w |

where σ 2b is the covariance of full‐sibs (= ½ V A+ ¼ V D+ V EC= 1/r (MS 1− MS 2) and σ 2w = ½ V A+ ¾ V D+ V EW= MS 2)

The limitation of this otherwise simple to implement design is its inability to provide the needed information to estimate all the parameters required by the model. The progeny from the design comprise full‐sibs or unrelated individuals. There is no further relatedness among individuals in the progeny. The breeder must make unjustifiable assumptions in order to estimate the genetic and environmental variance.

This design is for intermating a group of cultivars by natural crossing in an isolated block. It is most suited to species that are obligate cross‐pollinated (e.g. forage grasses and legumes, sugarcane, sweet potato), but especially those that can be vegetatively propagated. It provides an equal opportunity for each entry to be crossed with every other entry. It is critical that the entries be equally represented and randomly arranged in the crossing block. If 10 or less genotypes are involved, the Latin square design may be used. For a large number of entries, the completely randomized block design may be used. In both cases, about 20–30 replications are included in the crossing block. The ideal requirements are hard to meet in practice because of several problems, placing the system in jeopardy of deviating from random mating. If all the entries do not flower together, mating will not be random. To avoid this, the breeder may plant late flowering entries earlier.

Pollen may not be dispersed randomly, resulting in concentrations of common pollen in the crossing block. Half‐sibs are generated in a polycross because progeny from each entry has a common parent. The design is used in breeding to produce synthetic cultivars, recombining selected entries of families in recurrent selection breeding programs, or for evaluating the GCA of entries.

Design Iis a very popular multipurpose design for both theoretical and practical plant breeding applications ( Figure 4.5). It is commonly used to estimate additive and dominance variances as well as for evaluation of full‐ and half‐sib recurrent selection. It requires sufficient seed for replicated evaluation trials, and hence is not of practical application in breeding species that are not capable of producing large amounts of seed. It is applicable to both self‐ and cross‐pollinated species that meet this criterion. As a nested design, each member of a group of parents used as males is mated to a different group of parents. NC design I is a hierarchical design with non‐common parents nested in common parents.

Читать дальше