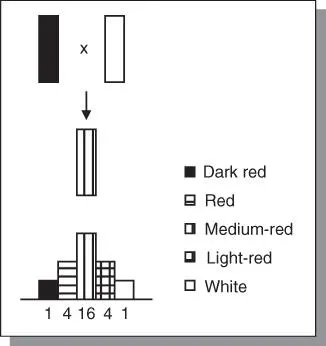

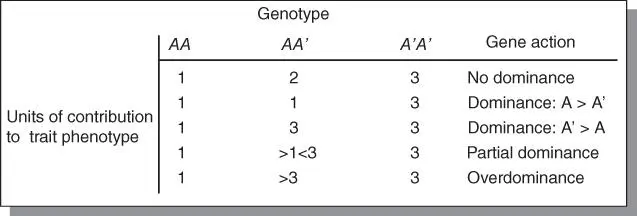

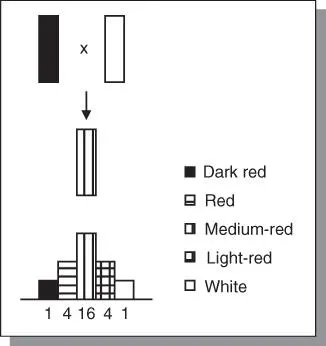

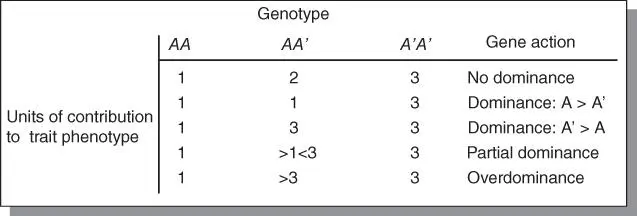

Figure 4.2(a)Nilsson‐Ehle's classical work involving wheat color provided the first formal evidence of genes with cumulative effect. (b) An illustration of gene action using numeric values.

The study involved only two loci. However, most polygenic traits are conditioned by genes at many loci. The number of genotypes that may be observed in the F 2is calculated as 3 n, where n = number of loci (each with two alleles). Hence, for 3 loci, the number of genotypes = 27, and for 10 loci, it will be 3 10= 59 049. Many different genotypes can have the same phenotype; consequently, there is no strict one‐to‐one relationship between genotype. For n loci, there are 3 ngenotypes and 2 n + 1 phenotypes. Many complex traits such as yield may have dozens and conceivably even hundreds of loci.

Other difficulties associated with studying the genetics of quantitative traits are dominance, environmental variation, and epistasis. Not only can dominance obscure the true genotype, but both the amount and direction can vary from one gene to another. For example, allele A may be dominant to a , but b may be dominant to B . It has previously been mentioned that environmental effects can significantly obscure genetic effects. Non‐allelic interaction is a clear possibility when many genes are acting together.

Number of genes controlling a quantitative trait

Polygenic inheritance is characterized by segregation at a large number of loci affecting a trait as previously discussed. Biometrical procedures have been proposed to estimate the number of genes involved in a quantitative trait expression. However, such estimates, apart from not being reliable, have limited practical use. Genes may differ in the magnitude of their effects on traits, not to mention the possibility of modifying gene effects on certain genes.

One gene may have a major effect on one trait, and a minor effect on another. There are many genes in plants without any known effects besides the fact that they modify the expression of a major gene by either enhancing or diminishing it. The effect of modifier genes may be subtle, such as slight variations in traits like shape and shades of color of flowers, or variation in aroma and taste in fruits. Those trait modifications are of concern to plant breeders as they conduct breeding programs to improve quantitative traits involving many major traits of interest.

4.2.4 Decision‐making in breeding based on biometrical genetics

Biometrical geneticsis concerned with the inheritance of quantitative traits. As previously stated, most of the genes of interest to plant breeders are controlled by many genes. In order to effectively manipulate quantitative traits, the breeder needs to understand the nature and extent of their genetic and environmental control. M.J. Kearsey summarized the salient questions that need to be answered by a breeder who is focusing on improving quantitative (and also qualitative) traits:

1 Is the character inherited?

2 How much variation in the germplasm is genetic?

3 What is the nature of the genetic variation?

4 How is the genetic variation organized?

By having answers to these basic genetic questions, the breeder will be in a position to apply the knowledge to address certain fundamental questions in plant breeding.

What is the best cultivar to breed?

As will be discussed later in the book, there are several distinct types of cultivars that plant breeders develop – pure lines, hybrids, synthetics, multilines, composites, etc. The type of cultivar is closely related to the breeding system of the species (self‐ or cross‐pollinated), but more importantly on the genetic control of the traits targeted for manipulation. As breeders have more understanding of and control over plant reproduction, the traditional grouping between types of cultivars to breed and the methods used along the lines of the breeding system have diminished. The fact is that the breeding system can be artificially altered (i.e. self‐pollinated species can be forced to outbreed, and vice versa). However, the genetic control of the trait of interest cannot be changed. The action and interaction of polygenes are difficult to alter. As Kearsey notes, breeders should make decisions on the type of cultivar to breed based on the genetic architecture of the trait, especially the nature and extent of dominance and gene interaction (see Section 4.2.5on gene action), more so than the breeding system of the species.

Generally, where additive variance and additive × additive interaction predominate, pure lines and inbred cultivars are appropriate to develop. However, where dominance variance and dominance × dominance interaction suggest overdominance predominates, hybrids would be successful cultivars. Open pollinated cultivars are suitable where a mixture of the above genetic architecture occurs.

What selection method would be most effective for improvement of the trait?

The kinds of selection methods used in plant breeding are discussed in Chapters 15–18. The genetic control of the trait of interest determines the most effective selection method to use. The breeder should pay attention to the relative contribution of the components of genetic variance (additive, dominance, epistasis) and environmental variance in choosing the best selection method. Additive genetic variance can be exploited for long‐term genetic gains by concentrating desirable genes in the homozygous state in a genotype. The breeder can make rapid progress where heritability is high by using selection methods that are dependent solely on phenotype (e.g. mass selection). However, where heritability is low, methods of selection based on families and progeny testing are more effective and efficient. When overdominance predominates, the breeder can exploit short‐term genetic gain very quickly by developing hybrid cultivars for the crop.

It should be pointed out that as self‐fertilizing species attain homozygosity following a cross, they become less responsive to selection. However, additive genetic variance can be exploited for a longer time in open‐pollinated populations because relatively more genetic variation is regularly being generated through the ongoing intermating.

Should selection be on single traits or multiple traits?

Plant breeders are often interested in more than one trait in a breeding program, which they seek to improve simultaneously. The breeder is not interested in achieving disease resistance only, but in addition, high yield and other agronomic traits. The problem with simultaneous trait selection is that the traits could be correlated such that modifying one affects the other. The concept of correlated traits is discussed next. Biometrical procedures have been developed to provide a statistical tool for the breeder to use. These tools are also discussed in this section.

Additional information on gene action is found in Supplemental Material 1 at the end of the regular chapters of the book. There are four types of gene action: additive, dominance, epistasis,and overdominance. Because gene effects do not always fall into clear‐cut categories, and quantitative traits are governed by genes with small individual effects, they are often described by their gene action rather than by the number of genes by which they are encoded. It should be pointed out that gene action is conceptually the same for major genes as well as minor genes, the essential difference being that the action of a minor gene is small and significantly influenced by the environment. A general way of distinguishing between these types of gene action based on interaction among alleles is as follows:

Читать дальше