Impact of breeding method on genetic variance

Additive genetic variance is known to decrease proportionally to the improvement following selection. In pure line selection, genetic variance is completely depleted with time, until further improvement is impossible. However, mutational events as well as genetic recombination can replenish some of the lost additive genetic variance. On the contrary, additive genetic variance cannot be depleted in intermating populations because auto conversion (self conversion) of non‐additive genetic variance to additive genetic variance occurs. This conversion occurs because heterozygotes become fixed into homozygotes.

Gene action may be estimated by creating various crosses (e.g. diallelee, partial diallelee, line × tester cross, biparental cross, etc.) and applying various biometrical analyses to estimate components of genetic variance. Additive genetic variance is very important to breeders because it is the only genetic variance that responds to selection. In addition to the components of genetic variance, combining ability variances may also be used to measure gene action.

Factors affecting gene action

Gene action is affected by several factors, the key one being the type of genetic material, mode of pollination, mode of inheritance, presence of linkage, as well as biometrical parameters (e.g. simple size, sampling method, and method of calculation). Alleles with a dominant, additive, or deleterious phenotypic effect affect heritability differently depending on whether they are in homozygous or heterozygous condition. Knowledge of the way genes act and interact will determine which breeding system optimizes gene action more efficiently and will elucidate the role of breeding systems in the evolution of crop plants.

Self‐pollinated materials (e.g. mass selected cultivar, multiline, varietal blends) express additive and additive epistasis. A pure line cultivar will have additive gene action but without genetic variation. On the other hand, products derived from cross‐pollinated species (e.g. composite variety, synthetic variety) will display additive, dominance, and epistatic gene action. F 1hybrid material will have no additive gene action and no genetic variation.

In terms of pollination, self‐pollinated species exhibit additive gene action since this gene action is associated with homozygosity. On the contrary, non‐additive gene action is associated with heterozygosity and hence is more prevalent in cross‐pollinated species than self‐pollinated ones. Simply inherited (qualitative, oligogenic) traits predominantly exhibit non‐additive and epistatic gene action, while polygenic traits are governed predominantly by additive gene action.

Gene action estimates are affected by the presence of genetic linkage. Estimates of additive gene action and dominance gene action can be biased up when the genes of interest are in the coupling phase (AB/ab). In the repulsion phase (Ab/aB), genes can cause estimates of dominance gene action to be biased upwards and additive action downwards.

4.2.8 Variance components of a quantitative trait

The genetics of a quantitative trait centers on the study of its variation. As D.S. Falconer stated, it is in terms of variation that the primary genetic questions are formulated. Further, the researcher is interested in partitioning variance into its components that are attributed to different causes or sources. The genetic properties of a population are determined by the relative magnitudes of the components of variance. In addition, by knowing the components of variance, one may estimate the relative importance of the various determinants of phenotype.

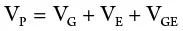

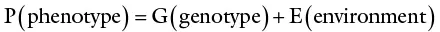

K. Mather expressed the phenotypic value of quantitative traits in this commonly used expression:

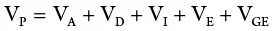

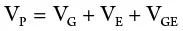

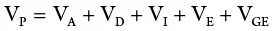

Individuals differ in phenotypic value. When the phenotypes of a quantitative trait are measured, the observed value represents the phenotypic value of the individual. The phenotypic value is variable because it depends on genetic differences among individuals, as well as environmental factors and the interaction between genotypes and the environment (called G × E interaction). A third factor (GE) is therefore added to the previous conceptual equation so that the total variance of a quantitative trait may be mathematically expressed as follows:

where V P= total phenotypic varianceof the segregating population; V G= genetic variance; V E= environmental variance; and V GE= variance associated with the genetic and environmental interaction.

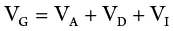

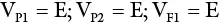

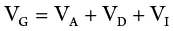

The genetic component of variance may be further partitioned into three components as follows:

where V A= additive variance(variance from additive gene effects); V D,= dominance variance(variance from dominance gene action); and V I= interaction(variance from interaction between genes). Additive genetic variance (or simply additive variance) is the variance of breeding values and is the primary cause of resemblance between relatives. Hence V Ais the primary determinant of the observable genetic properties of the population, and of the response to the population to selection. Further, V Ais the only component that the researcher can most readily estimate from observations made on the population. Consequently, it is common to partition genetic variance into two – additive versus all other kinds of variance. This ratio, V A /V P, gives what is called the heritabilityof a trait, an estimate that is of practical importance in plant breeding.

The total phenotypic variance may then be rewritten as follows:

To estimate these variance components, the researcher uses carefully designed experiments and analytical methods. To obtain environmental variance, individuals from the same genotype or replicates are used.

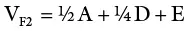

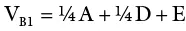

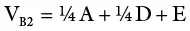

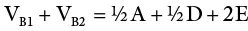

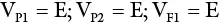

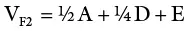

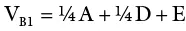

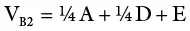

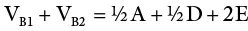

An inbred line (essentially homozygous) consists of individuals with the same genotype. An F 1generation from a cross of two inbred lines will be heterozygous but genetically uniform. The variance from the parents and the F 1may be used as a measure of environmental variance (V E). K. Mather provided procedures for obtaining genotypic variance from F 2and backcross data. In sum, variances from additive, dominant, and environmental effects may be obtained as follows:

(where V P1and V P2are variances for the parents in a cross; V F1is the variance of the resulting hybrid; F 2is the variance of the F 2population; A and D are additive and dominant effects, respectively; E is the environmental effect; V B1and V B2are backcross variances). This represents the most basic procedure for obtaining components of genetic variance since it omits the variances due to epistasis, which are common with quantitative traits. More rigorous biometric procedures are needed to consider the effects of interlocular interaction.

Читать дальше