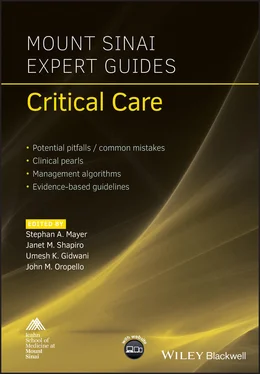

Mount Sinai Expert Guides

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mount Sinai Expert Guides» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mount Sinai Expert Guides

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mount Sinai Expert Guides: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mount Sinai Expert Guides»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mount Sinai Expert Guides — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mount Sinai Expert Guides», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Modes:B‐mode (brightness): standard scanning mode using different shades of gray to provide structural information in 2D image.M‐mode (motion): temporal measurement of structures moving toward or away from probe.Color Doppler: distinguishes vascular from non‐vascular structures and shows direction of flow.

Basic terminology

Echogenicity: brightness (amplitude) of image.

Hyperechoic/echogenic: structure appears brighter/whiter by generating more echoes than surrounding tissue.

Hypoechoic: structure appears darker than surrounding tissue by generating few echoes.

Isoechoic: same brightness as surrounding tissue.

Anechoic: area appears black due to complete absence of echoes.

Artifacts of US imaging

Shadowing: partial or total reflection of US waves (gallstones, ribs).

Posterior enhancement: area behind anechoic fluid‐filled structures appears brighter (bladder).

Edge artifact: shadow formed by refraction of US wave at edge of rounded structure.

Mirror artifact: image of structure duplicated as US wave reflects off highly reflective surface (diaphragm).

Reverberation artifact: US wave bounces between two highly reflective surfaces (pleura).

Ring‐down artifact: appearance of needle tip as a hyperechoic structure casting a narrow shadow.

Procedure

Cardiac ultrasonography

Probe selection and orientation

Use phased array ‘cardiac‘ probe.

Conventional cardiology screen/probe orientation is to position the screen index marker on the right side of the screen (reverse of general radiology convention).

Scanning technique

There are four standard views ( Figure 4.2).

Parasternal long axis. Position probe just left of sternum at the third or fourth intercostal space. When using conventional cardiology orientation (marker on right side of screen), point probe indicator towards patient’s right shoulder. If you prefer keeping the screen marker fixed on the left side while obtaining views consistent with conventional cardiology imaging, simply point probe in opposite direction towards patient’s left hip. Otherwise, images will be reversed.

Parasternal short axis. Rotate probe 90° from long axis view to obtain circular short axis view of left ventricle. For conventional cardiology orientation, this means pointing probe towards the patient’s left shoulder. For general radiology orientation, point probe towards patient’s right hip. Angling probe through short axis views allows visualization of different segments of the left ventricle, including apex, papillary muscles (mid‐section), mitral valve (base of heart), and aortic valve (‘Mercedes Benz’ sign).

Apical four chamber. Using same orientation as short axis view, slide probe leftward – lateral to nipple line (men) or inframammary crease (women) – to point of maximal impulse. Position probe so ventricular septum is in center of US screen. The left heart will be on right side of screen and vice versa.

Subxiphoid. Position probe just below subxiphoid and angle cephalad toward the patient’s left shoulder using the liver as an acoustic window. If using conventional cardiology orientation, point probe towards patient’s left side. Otherwise, point probe towards patient’s right side. Transition to evaluating the inferior vena cava (IVC) from this view.

Clinical application

Assess for pericardial effusion or tamponade:Effusion appears as anechoic area within pericardial space.Large effusions tend to wrap circumferentially around heart.Clotted blood or exudates appear more echogenic.If effusion is identified, observe closely for diastolic collapse of right heart which indicates tamponade physiology.

Determine global left ventricular (LV) function, systolic function and size:Contractility is best determined using parasternal views.‘Good’ contractility: LV walls almost touch during systole and nearly obliterate ventricular cavity; anterior leaflet of mitral valve moves vigorously in parasternal long axis view.‘Poor’ contractility: minimal wall movement or change in ventricular cavity between systole and diastole.Small ventricular cavity in hypovolemic conditions.

Assess for right ventricular (RV) strain ( Figure 4.3):Classic sign of massive pulmonary embolus.RV dilation: RV size exceeds LV size.Paradoxical septal wall motion or ’D’ sign: best seen in parasternal short view; normal LV is circular but increased RV pressure flattens or bows interventricular septum into LV during diastole.McConnell’s sign: RV dysfunction with characteristic sparing of apex; often described as ‘invisible man jumping on trampoline at RV apex’.

BOTTOM LINE/CLINICAL PEARLS

Ribs block US waves and obscure views of heart. Make fine adjustments by rotating and angling cardiac probe so the US beam is parallel to ribs.

Epicardial fat pad may be mistaken for an effusion; it is most prominent anteriorly.

Some views will be difficult to obtain in individual patients. Turning patient into left lateral decubitus position may improve views.

Inferior vena cava (ultrasonography)

Probe selection and orientation

Use phased array ‘cardiac’ probe or curvilinear probe.

Same screen/probe orientation as for subxiphoid view of heart.

Scanning technique

Start with subxiphoid view of heart, then rotate probe 90° so probe indicator points cephalad.

Slide probe slightly right of midline until IVC is visualized in longitudinal plane.

Identify where IVC transitions into right atrium to confirm visualization of IVC versus abdominal aorta ( Figure 4.4).

Measure IVC diameter 2 cm caudal to junction of IVC and right atrium.

Use M‐mode on IVC to graphically visualize respiratory variation in IVC caliber.

Clinical application

Estimate intravascular volume and monitor response to fluid challenges by evaluating IVC diameter and collapsibility ( Table 4.3).

Correlation between central venous pressure (CVP) and IVC diameter and percentage change with respiratory variation.

If IVC diameter is <1 cm → higher probability of fluid responsiveness.

If IVC diameter is >2.5 cm → lower probability of fluid responsiveness.

IVC diameter between 1 and 2.5 cm → indeterminate probability.

Table 4.3 Intravascular volume estimation.

| Intravascular volume status * | IVC caliber | IVC collapsibility | CVP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume depleted | Small (<1 cm) | >50% | <10 cmH 2O |

| Volume overloaded | Large (>2.5 cm) | <50% | >10 cmH 2O |

*IVC distention with minimal respiratory variation may occur in clinical scenarios other than volume overload (e.g. cardiac tamponade).

BOTTOM LINE/CLINICAL PEARLS

Do not mistake pulsatile abdominal aorta for IVC. If it is the IVC, the vessel can be seen entering the right atrium; also look for hepatic vein entering the IVC.

‘Plump IVC’ does not always indicate volume overload. Assess cardiac function prior to IVC to provide context for IVC findings.

Lung ultrasonography

Probe selection and orientation

Use phased array ‘cardiac’ probe (adequate for majority of lung examinations).

Use linear array ‘vascular’ probe for detailed exam of pleural surface.

Point probe indicator toward patient’s head (general radiology convention).

Scanning technique

Position probe over rib interspace so rib shadows are on each side of US screen.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mount Sinai Expert Guides»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mount Sinai Expert Guides» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mount Sinai Expert Guides» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.