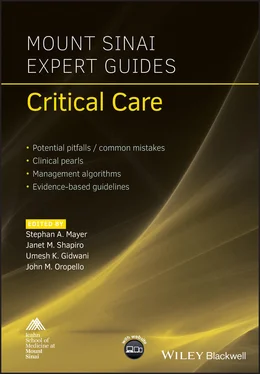

Mount Sinai Expert Guides

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mount Sinai Expert Guides» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mount Sinai Expert Guides

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mount Sinai Expert Guides: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mount Sinai Expert Guides»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mount Sinai Expert Guides — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mount Sinai Expert Guides», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To confirm tracheal placement, the ETT is connected to a bag ventilation circuit and ventilated, observing bilateral chest rise, condensation in the ETT, and, most importantly, continuous end‐tidal CO2 via capnography – considered the gold standard. If continuous end‐tidal CO2 is not detected, esophageal intubation should be suspected and laryngoscopy should be reattempted.

The distal tip of the ETT should lie beyond the vocal cords but above the carina, avoiding mainstem intubation. In adults this typically correlates to 21–23 cm at the patient’s lip. A CXR should be ordered immediately after placement to confirm proper position.

Video 1.1 demonstrates a successful endotracheal intubation of a morbidly obese patient. Note the ready availability of all necessary equipment including suction, laryngoscope, ETT, and oral airway. Also, note the proper patient positioning, including approximately 35° cervical flexion aided by the use of multiple blankets to ramp the shoulders as well as slight head extension. This combination allows for a nearly straight line of sight from the open mouth to the trachea. A MAC blade is used in the left hand and it sweeps the tongue to the side after the right hand scissors the mouth open. The blade is placed in the vallecula. Force is applied in a 45° direction to visualize the glottis opening, not rocked back against the upper incisors. The ETT is directly visualized as it passes between the vocal cords. The laryngoscope is then removed, and the ETT cuff is inflated with no more than 10 mL of air. While bilateral breath sounds and presence of fog in the ETT should indicate proper placement, the gold standard for proper placement is continuous end‐tidal CO2 waveform capnography.

Rapid sequence induction

This is a specialized method of induction used when the risk of pulmonary aspiration is particularly high.

The goal is to achieve optimal intubating conditions in the fastest time possible.

After preoxygenation, cricoid pressure is held by an assistant while induction agents (see Chapter 2for agents and dosages) are given followed by 1.5 mg/kg of succinylcholine or 1 mg/kg of rocuronium, and laryngoscopy is attempted without mask ventilation. Cricoid pressure is maintained until confirmation of tracheal intubation is observed.

Difficult airway

Most difficult airways can be anticipated, and care should always be taken to recognize them with proper assessment, as unanticipated airway difficulties subject the patient to potential hypoxia, cardiovascular collapse, and neurologic damage.

A distinction should be made as to whether the potential difficulty lies in the ability to mask ventilate, to intubate, or both.

A good rule of thumb is to never intentionally make a patient apneic unless one is certain that ventilation will be possible.

Proper planning and set‐up, availability of equipment, positioning, and adequate preoxygenation become even more important when airway difficulty is suspected.

In the setting of an anticipated difficult airway, additional tools such as video laryngoscopes, fiberoptic bronchoscopes as well as additional providers with the ability to provide surgical airway access should be immediately available prior to induction.

If intubation and mask ventilation are predicted to be difficult, airway topicalization with local anesthetic and fiberoptic intubation while awake with minimal sedation is the gold standard. This should be performed with an open emergency tracheostomy set nearby as well as a provider capable of performing a surgical airway procedure. One may also attempt an ‘awake look’ by titrating small doses of a non‐apnea‐inducing hypnotic‐like ketamine until a brief exam under video or direct laryngoscopy is tolerated. If this view is acceptable, one can then induce as usual and intubate the patient with the particular device.

In the undesirable scenario where intubation is found to be difficult after induction (unanticipated difficult intubation), an attempt should be made to mask ventilate the patient and assistance should be called. If mask ventilation is easy, one can then attempt another method of intubation while confirming proper positioning and bed height. If mask ventilation is difficult, one should attempt the two‐handed mask ventilation technique or placement of an oral airway. If still difficult, supraglottic airway placement such as an LMA should be considered. If ventilation remains poor, emergency invasive airway placement is likely required.

Cervical spine disease

Cervical spine injury, whether due to trauma, previous cervical fusion resulting in limited mobility, or inflammation from rheumatoid arthritis can present challenges for airway management. The presence of a cervical collar can also make airway management difficult. Evaluation of cervical flexion and extension is prudent, and, in the case of trauma, discussions with spine surgeons regarding cervical spine stability should take place.

In the setting of an unstable cervical spine injury, intubation with a fiberoptic bronchoscope should take place. Alternatively, direct laryngoscopy while an assistant performs inline stabilization (holding the head firmly with both hands so as to not allow unintentional cervical flexion or extension by the laryngoscopist) may be attempted.

Extubation

While the decision to extubate is partly driven by objective data, it also relies upon clinical judgment.

Patients should have stable vital signs, an SpO2 of at least 90% or an FiO2 of 40% or less, PaCO2 <50 mmHg unless there is known chronic CO2 retention, adequate tidal volumes on minimal pressure support, intact airway reflexes, and baseline mental status.

One should also consider the specific situation such as difficulty of intubation, barriers to reintubation (e.g. jaw wired shut after maxillofacial surgery, significant airway edema), fluid balance, and acid–base balance.

If there is any question of airway patency, one may consider performing a leak test (deflating the ETT cuff and listening for air movement around the ETT and observing a decrease in tidal volume) or extubating over an ETT exchanger with a backup ETT available in case reintubation becomes necessary.

Patients with baseline pulmonary dysfunction may benefit from being extubated to BIPAP or HFNC.

Complications of intubation

Airway trauma

Instrumentation of the airway can cause trauma to soft tissues as well as to teeth and lips.

Although less common with modern ETTs, overinflation of cuffs (typically greater than 30 mmHg) can cause tissue ischemia, leading to inflammation and possibly tracheal stenosis as well as vocal cord paralysis from compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Vocal cord paralysis can produce hoarseness and susceptibility to aspiration.

Physiologic effects of airway instrumentation

Hypotension is a common response to induction and should be anticipated, especially in critically ill patients.

Hypertension and tachycardia can be seen if inadequate anesthetic is provided.

Laryngospasm, an involuntary closure of the laryngeal muscles, is a response to airway stimulation in the setting of light anesthesia. Severe hypoxia, from the inability to mask ventilate through the closed larynx, can result. Treatment includes gentle positive pressure with a mask. If this fails, deepening the plain of anesthesia as well as giving succinylcholine will typically relax the musculature.

Aspiration

Critically ill patients often require airway management in the undesirable setting of a full stomach, or mechanical or physiologic motility disorders, making aspiration of gastric contents a feared complication.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mount Sinai Expert Guides»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mount Sinai Expert Guides» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mount Sinai Expert Guides» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.