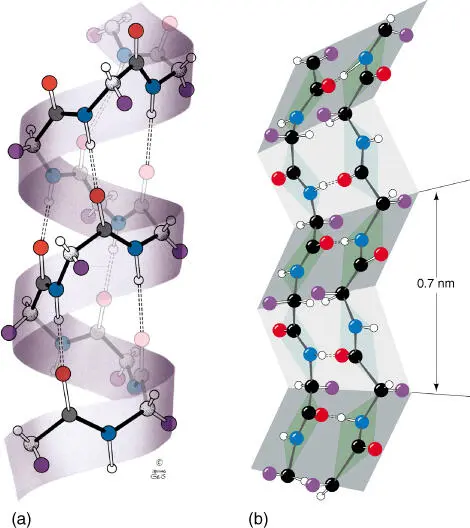

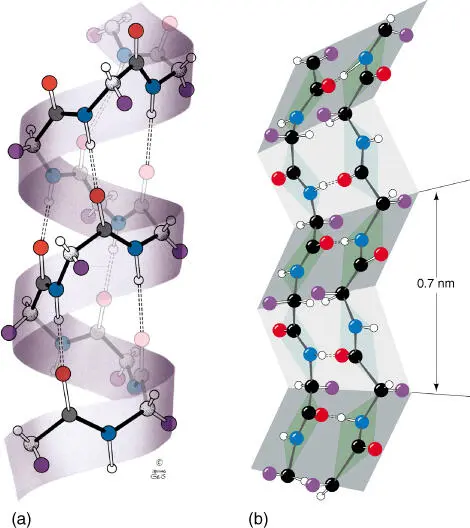

Figure 2.11 Importance of hydrogen bonds for the construction of α ‐helix and β ‐sheet structures. (a) The right twisting helix has 3.6 residues per turn. The dotted lines represent the hydrogen bonds between CO and NH groups. (b) The zigzag‐shaped representation of a β ‐pleated sheet. Dotted lines symbolize hydrogen bonds. The side chains alternate between being present below and above the folded plane.

Source: Voet et al. (2016). Reproduced with permission of John Wiley and Sons.

A β‐sheet structureelement is often found at the inner core of many proteins. The β ‐pleated sheet can appear between neighboring polypeptide chains that have the same orientation ( parallel chain). When a polypeptide chain folds back on itself and is aligned in parallel, the chains are termed antiparallel chains. In both cases, the chains are being held strongly together by hydrogen bonds ( Figure 2.11).

An α‐helixforms when a single peptide chain winds around itself and forms a sturdy cylinder. In doing so, a hydrogen bond forms between each fourth peptide bond (i.e. between the CO group of one peptide bond and the NH group of the other peptide bond). This results in the formation of an ordered helix with a complete turn every 3.6 amino acids. Short α ‐helix structures can be found in membrane proteins that possess a transmembrane region. In this case, the α ‐helix contains only amino acids with nonpolar residues. The nonpolar residues are oriented toward the outside of the helix and shield the hydrophilic backbone of the peptide chain and interact with the lipophilic components of the phospholipids.

In fibrous proteins (e.g. α ‐keratin), two or three longer helices can twist around each other ( coiled coil) and form long ropelike structures.

The structure of proteins is very complex, because there are thousands of covalent and noncovalent bonding possibilities between the atoms of the peptide chains and the amino acid residues. Through X‐rayand nuclear magnetic resonance ( NMR )analysis, the spatial structures of many hundreds of proteins have been determined. Structure analysis is a challenge not only for basic research but also for applied pharmaceutical research. If the structure or binding sites of a receptor or enzyme are known in detail, it should be possible to designnew active substances that have the correct fit and act either as an agonist or as an antagonist. Successes in rational drug designso far concern active substances in the area of AIDS (HIV protease inhibitors; Viracept, Agenerase) and influenza (neuraminidase inhibitors: Relenza, Tamiflu).

There are four structural levels of protein structure:

Primary structure. Primary structure corresponds to the amino acid sequence.

Secondary structure. Secondary structure corresponds to α‐helix and β‐pleated sheet formations.

Tertiary structure. Tertiary structure corresponds to the three‐dimensional conformation of a polypeptide chain.

Quaternary structure. If a protein complex consists of several subunits (i.e. hemoglobin), then the entire structure is referred to as the quaternary structure.

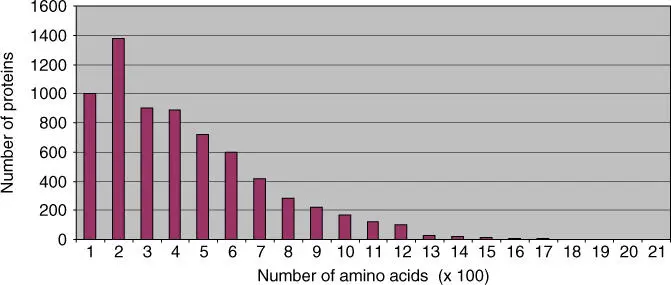

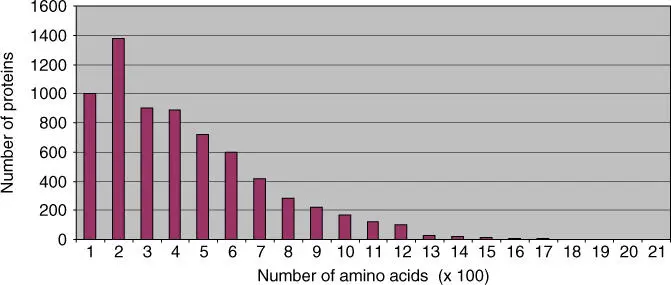

The proteins of a cell usually contain between 50 and 2000 amino acid residues. Theoretically, each of the 20 amino acids can appear at each location of a polypeptide chain. In an oligopeptide, with a length of four amino acids, there are 20 × 20 × 20 × 20 = 160 000 different oligopeptides. The number of possible peptide molecules can be calculated as 20 n, where n denotes the chain length. For a protein with the average length of 300 amino acids ( Figure 2.12), 20 300= 10 390possible variations are derived. However, not even our universe has that many atoms. From the great number of variants, only a comparatively small number was seemingly realized by nature. Through the course of evolution, many more proteins have been created. However, following natural selection only those proteins that have proven to be of value remain. During the course of evolution, protein familiesderiving from the first proteins with defined functions have developed through gene duplication. The original sequence has been changed in the new proteins.

Figure 2.12 Size of proteins in yeast ( Saccharomyces cerevisiae ). The yeast genome project allowed a first estimate of the size of yeast proteins.

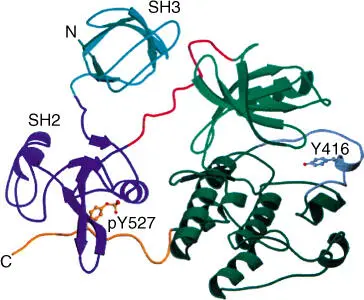

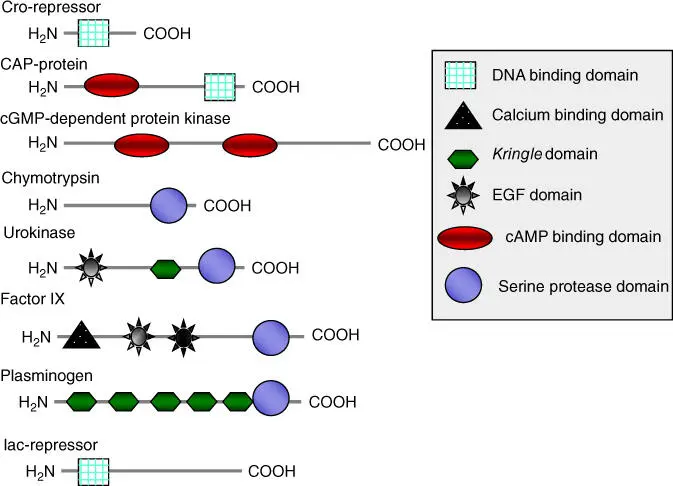

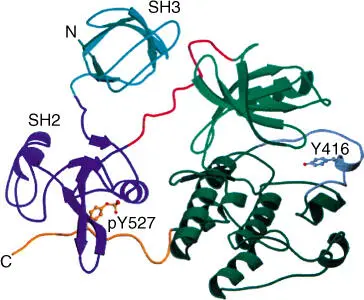

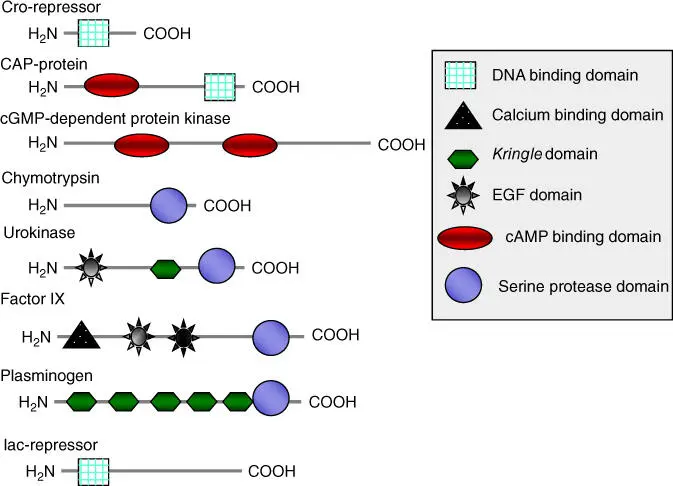

During analysis of genome projects, individual structural domainsof many proteins have been identified with the help of bioinformatics. Large proteins are usually made up of several functional domain or modules. Domains usually have defined structures and functions (Figures 2.13and 2.14). They often correspond to the exons in a eukaryotic gene(see Section 4.2). They developed in early evolution, obviously independent of each other. In a later evolutionary phase, the gene sections coding for a domain were newly combined. Through domain shuffling, proteins with new characteristics could thus be created. As a consequence, most proteins can be seen as variants of previously existing proteins or of their domains. Figure 2.13shows as an example the structure of an Src protein that has four domains. Examples for domain shuffling are illustrated in Figure 2.14. Domain shuffling is important for the explanation of evolutionary development. It is not only individual point mutations that bring evolutionary advancement but also mainly new combinations of functional modules (prefabricated building blocks).

Figure 2.13 Structure of Src protein with four domains. The four domains are the (a) small kinase domain, (b) large kinase domain, (c) SH2 domain, and (d) SH3 domain.

Figure 2.14 Occurrence of domains in different proteins.

Many proteins contain binding sitesfor ligands; ligands can be not only lower‐molecular‐weight substances but also macromolecules such as nucleic acids or other proteins. The binding of a ligand to a binding site can be viewed as a molecular recognition process. Such molecular recognition processes are common in the cell, but these processes are only understood in detail in a few cases. However, these processes have an important relevance to cell function, metabolism, and “life” that should not be underestimated. Experiments in structural biology have already shown that the binding of a ligand in a binding site functions according to the lock‐and‐key principle. The binding sitehas a specific spatial structure in which a ligand fits selectively. Binding of the ligand involves the formation of several noncovalent bonds ( Figure 2.15) between the functional groups of the ligand and those of the protein. Binding generally brings about a change of the protein conformation (induced fit). The binding site is not formed by amino acid residues that lie beside each other on the peptide chain, but often consists of amino acids located in different parts of a peptide chain and spatially form a binding site by appropriate specific folding ( Figure 2.15).

Читать дальше

![Andrew Radford - Linguistics An Introduction [Second Edition]](/books/397851/andrew-radford-linguistics-an-introduction-second-thumb.webp)