Soreness of the tongue, which may be due to a variety of reasons, including anaemia, vitamin B complex deficiency, and hormonal imbalance.

Black hairy tongue – due to overgrowth of tongue papillae, stained by chromogenic bacteria, mouthwash (e.g. chlorhexidine gluconate), or smoking. Looks alarming, but is not serious.

Geographic tongue (also called benign migratory glossitis) – smooth map‐like irregular areas on the dorsal surface (where the papillae are missing), which come and go. It can be harmless, but is sometimes sore and often runs in families. It can also be an indication of other systemic conditions [7].

Piercing of the tongue can also cause problems and the educator should be able to advise patients on this matter (see Chapter 22).

The educator must know that the floor of the mouth consists of a muscle called the mylohyoid and associated structures.

Incredible stuff, saliva! It is often taken for granted, and patients only realise how vital it is to the wellbeing of the oral cavity and the whole body, when its flow is diminished (see Chapter 7). Saliva is secreted by three major and numerous minor salivary glands. The minor glands are found in the lining of the oral cavity, on the inside of the lips, the cheeks, the palate, and even the pharynx.

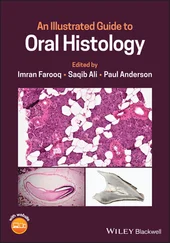

The three major salivary glands ( Figure 1.12) are as follows:

1 Parotid gland – situated in front of the ear. It is the largest salivary gland and produces 25% of the total volume of saliva [7]. It makes serous (watery) saliva, which is transported into the oral cavity by the parotid duct that opens adjacent to the upper molars. The parotid gland swells during mumps (parotitis).

2 Submandibular gland – situated beneath the mylohyoid muscle towards the base of the mandible. It is the middle of the three glands, in both size and position, and produces a mixture of serous and mucous saliva. It accounts for around 70% of total saliva and opens via the submandibular duct on the floor of the mouth [7].When dental nurses assist the dentist, they may occasionally notice a small fountain as the saliva appears from this duct (which can also happen when yawning). Figure 1.12 Major salivary glands.Source: From [8]. Reproduced with permission of Blackwell.

3 Sublingual gland – is also situated beneath the anterior floor of the mouth under the front of the tongue. It produces 5% of total saliva [7], mainly in the form of mucous, which drains through numerous small ducts on the ridge of the sublingual fold (the area next to the frenulum beneath the anterior of tongue).

Saliva is made up of 99.5% water and 0.5% dissolved substances, although the composition varies between individuals [7].

Dissolved substances include:

Mucins – these are glycoproteins that give saliva its viscosity (stickiness), lubricate the oral tissues, and are the origin of the salivary pellicle (the sticky film which forms on teeth within minutes of cleaning).

Enzymes – there are many, but the OHE needs only to remember the main ones:Salivary amylase (ptyalin), which converts starch into maltose.Lysozyme, which attacks the cell walls of bacteria, thus protecting the oral cavity from invading pathogens.

Serum proteins – albumin and globulin (saliva is formed from serum; the watery basis of blood).

Waste products – urea and uric acid.

Gases – oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide in solution. The latter vaporises when it enters the mouth and is given off as a gas.

Inorganic ions – including sodium, sulphate, potassium, calcium, phosphate, and chloride. The important ones to remember are calcium and phosphate ions, which are concerned with remineralisation of the teeth after an acid attack (see Chapter 5) and the development of calculus (see Chapter 2).

Saliva also contains large numbers of microorganisms and remnants of food substances.

There are eight main functions of saliva:

1 Aids mastication and deglutition – mucous helps form the food bolus.

2 Oral hygiene – washing and antibacterial action helps control disease of the oral cavity. Lysozyme controls bacterial growth. This is why saliva is said to have antibacterial properties, and why animals instinctively lick their wounds.

3 Speech – a lubricant. For example, nervousness = production of adrenaline = reduction in saliva = dry mouth.

4 Taste – saliva dissolves substances and allows the taste buds to recognise taste.

5 Helps maintain water balance (of body) – when water balance is low, saliva is reduced, producing thirst.

6 Excretion – trace amounts of urea and uric acid (a minor role in total body excretion).

7 Digestion – salivary amylase begins the breakdown of cooked starch (a relatively minor role in the whole digestive process, but important in relation to sucrose intake and oral disease).

8 Buffering action – helps maintain the neutral pH of the mouth. The bicarbonate ion is vital to the health of the mouth as it is concerned with the buffering action of saliva. The average resting pH of the mouth (when no food has just been consumed) is 6.7. This is neutral, neither acid nor alkaline. (pH is a symbol used to indicate measurement of acidity or alkalinity of substances or liquids, and stands for the German term potenz Hydrogen.)

Here are some general points of interest about saliva:

More is secreted when required (reflex action).

Composition varies according to what is being eaten (e.g. more mucous with meat).

Average amount produced daily by adults is 0.5–1 L. Certain medical conditions and disabilities cause the overproduction of saliva, resulting in dribbling (e.g. patients with Down’s syndrome and Parkinson’s disease, and fungal infections, such as angular cheilitis – see Chapter 8).

Flow almost ceases during sleep.

Saliva is sterile until it enters the mouth.

Saliva tests can be used to solve crimes, since saliva contains deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which can be used to help identify individuals. Dental companies sell saliva testing kits, which can be used by OHEs to demonstrate saliva pH to patients.

Other additives within the mouth

Although saliva entering the mouth is sterile, it soon loses this property as it collects organic materials that are already present, including:

Microorganisms: bacteria (mainly streptococci), viruses (e.g. herpes simplex), and fungi (e.g. Candida albicans).

Leucocytes (white blood cells), which fight infection. Not present in edentulous (toothless) babies or in saliva collected from the duct, so presumed to come from gingival crevice after teeth erupt.

Dietary substances (meal remains).

1 1. Thibodeau, G.A. & Patton, K.T. (2002) Anatomy and Physiology. 5th edn. Mosby, Missouri.

2 2. Lang, N.P., Mombelli, A. & Attström, R. (2003) Dental plaque and calculus. In: Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry (eds. J. Lindhe, T. Karring & N.P. Lang N.P.), 4th edn, pp. 81–105. Blackwell Munksgaard, Oxford.

3 3. Phillips, S. Oral embryology, histology and anatomy. In: Clinical Textbook of Dental Hygiene and Therapy (ed. S.L Noble), 2nd edn. pp. 3–5. Wiley‐Blackwell, Oxford.

4 4. Cleft Lip & Palate Association. (2019). What is Cleft Lip & Palate? Available at: https://www.clapa.com/what‐is‐cleft‐lip‐palate/[accessed 13 March 2019].

5 5. Watkins, S.E. , Meyer, R.E., Strauss, R.P., Aylsworth, A.S. (2014) Classification, epidemiology, and genetics of orofacial clefts. Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 41(2), 149–163.

Читать дальше