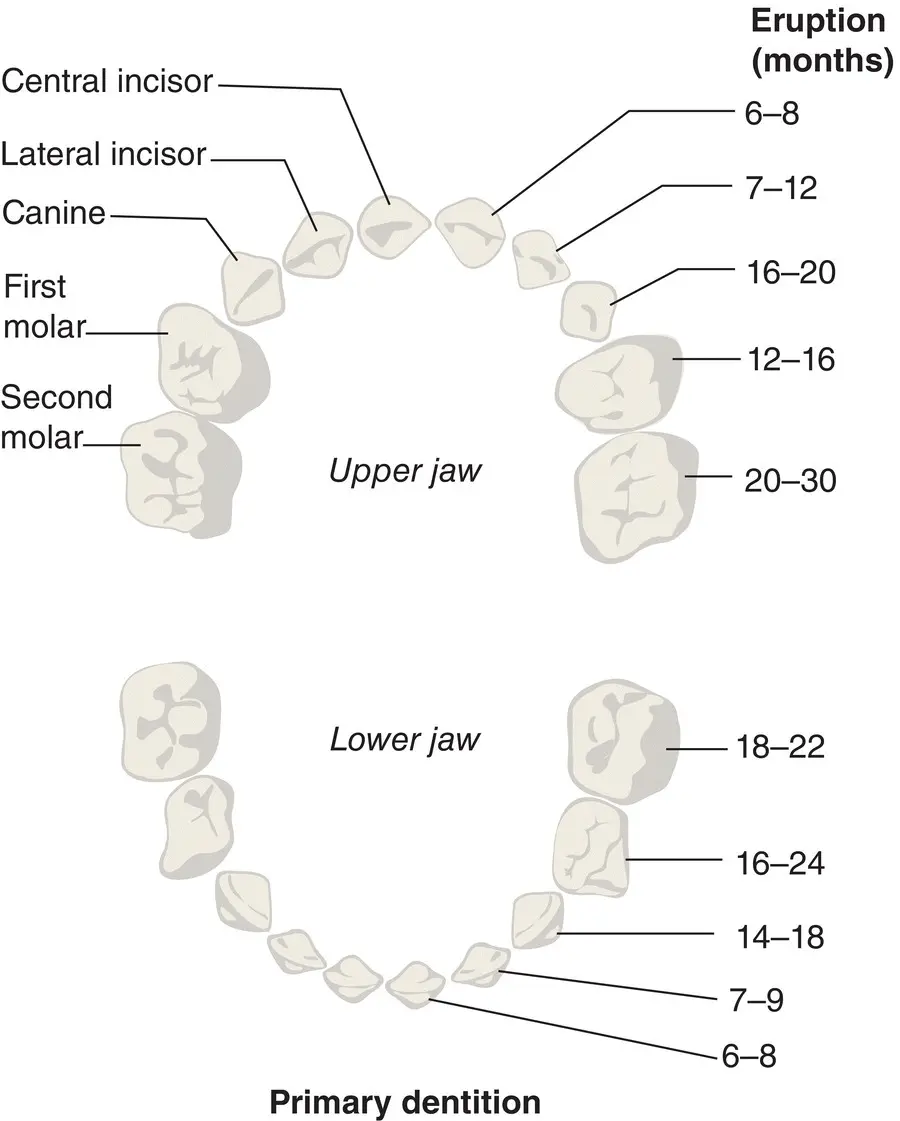

1 Primary (deciduous) dentition – consisting of 20 baby teeth.

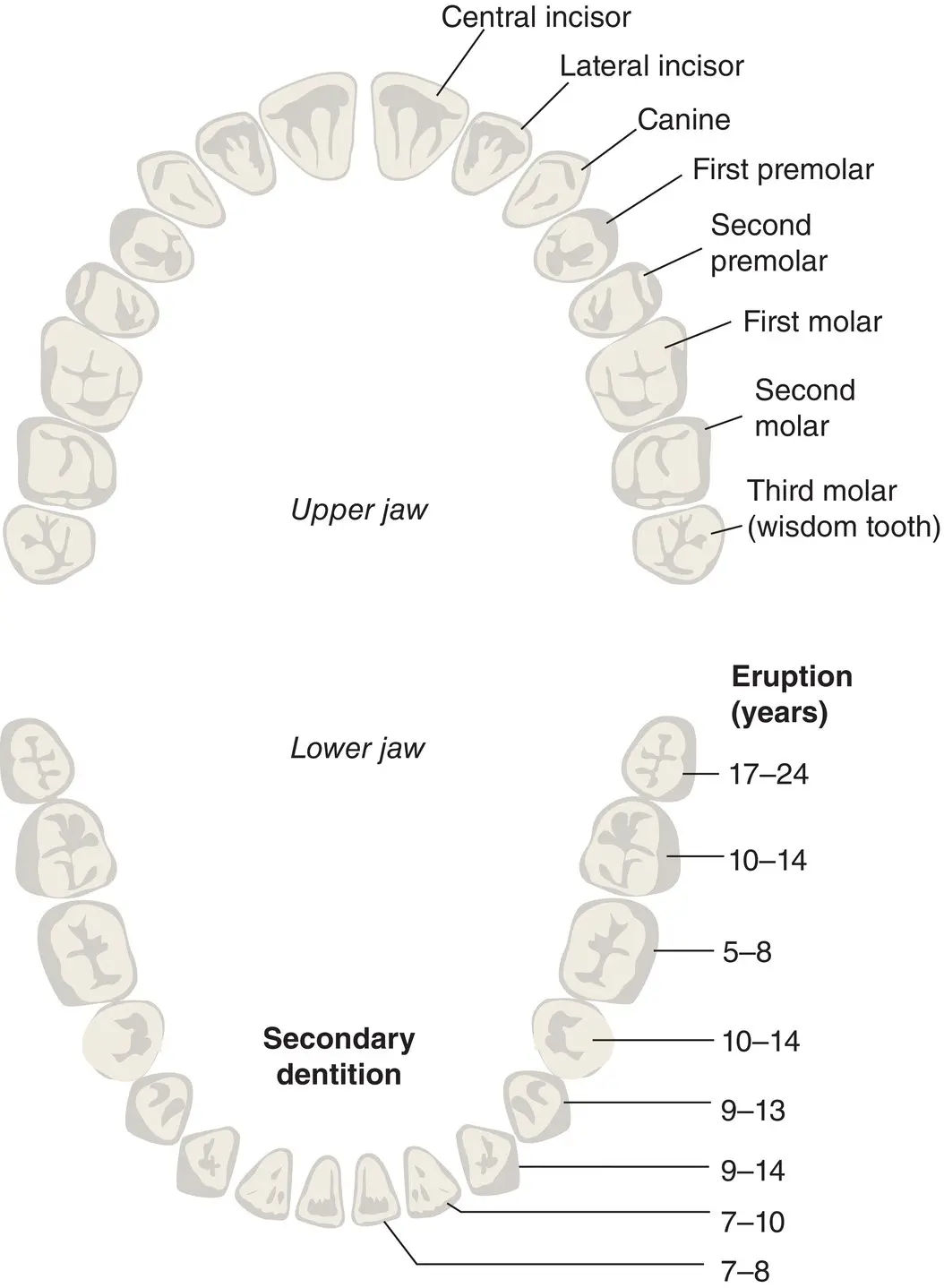

2 Secondary (permanent) dentition – consisting of 32 adult teeth.

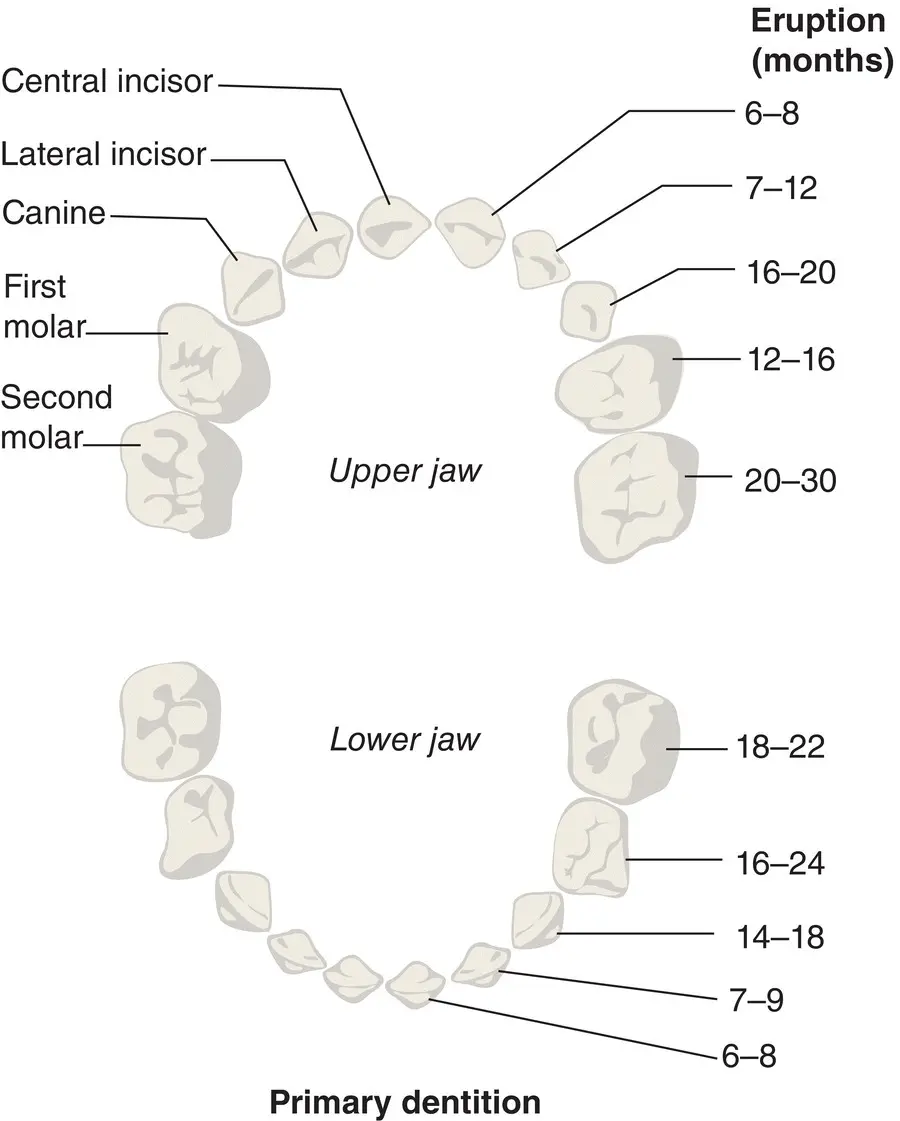

There are three types of deciduous teeth that make up the primary dentition ( Figure 1.7): incisors, canines, and molars (first and second). Table 1.1details their notation (the code used by the dental profession to identify teeth), approximate eruption dates, and functions.

Figure 1.7 Primary dentition.

Source: From [1]. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Table 1.1 Primary dentition (notation, approximate eruption dates, and functions).

| Tooth |

Notation |

Approximate eruption date |

Function |

| Incisors |

(a & b) |

6–12 months (usually lowers first) |

Biting |

| First molars |

(d) |

12–24 months |

Chewing |

| Canines |

(c) |

14–20 months |

Tearing |

| Second molars |

(e) |

18–30 months |

Chewing |

Table 1.2 FDI World Dental Federation notation for deciduous (primary) dentition.

| Patient’s upper right (5) |

Patient’s upper left (6) |

| 55 54 53 52 51 |

61 62 63 64 65 |

| 85 84 83 82 81 |

71 72 73 74 75 |

| Patient’s lower right (8) |

Patient’s lower left (7) |

Table 1.2details the FDI World Dental Federation notation for primary dentition, which is a charting system commonly used by dentists to associate information to a specific tooth; where the quadrant number is the first digit applied, and the second number identifies the individual tooth.

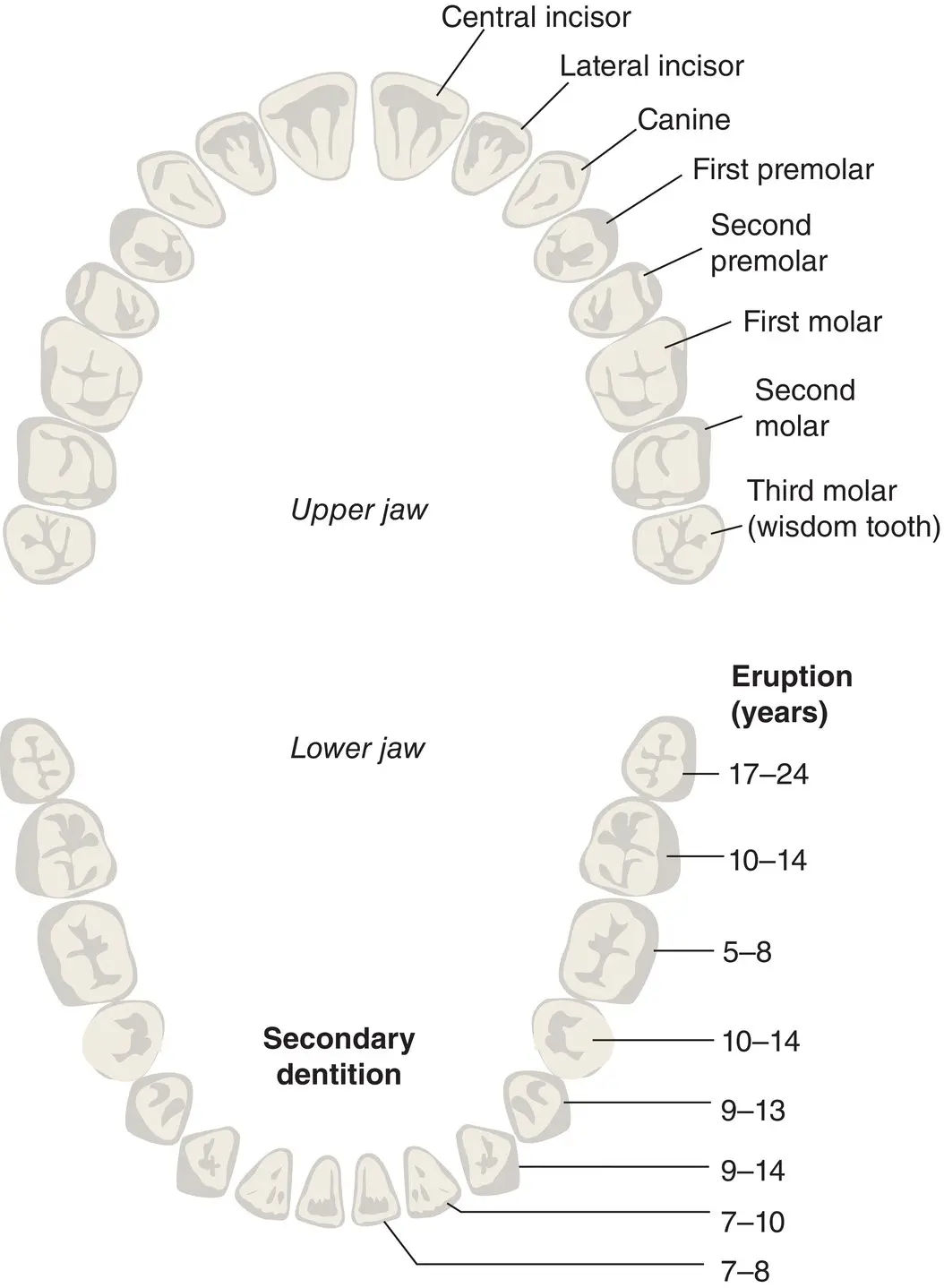

There are four types of permanent teeth that make up the secondary dentition ( Figure 1.8): incisors, canines, premolars, and molars. Table 1.3details their notation, approximate exfoliation/eruption dates, and functions. Table 1.4details the FDI World Dental Federation notation for secondary dentition.

It is important to remember that these exfoliation/eruption dates are only approximate and vary considerably in children and adolescents. The educator should be prepared to answer questions from parents who are worried that their child’s teeth are not erupting at the same age as their friends’ teeth. Parents often do not realise, for example, that no teeth fall out to make room for the first permanent molars (sixes), which appear behind the deciduous molars.

Figure 1.8 Secondary dentition.

Source: From [1]. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Table 1.3 Secondary dentition (notation, approximate exfoliation/eruption dates, and functions).

| Tooth |

Notation |

Approximate exfoliation/eruption dates |

Function |

| First molars |

(6) |

6–7 years |

Chewing |

| Lower central incisors |

(1) |

6–7 years |

Biting |

| Upper central incisors |

(1) |

6–7 years |

Biting |

| Lower lateral incisors |

(2) |

7–8 years |

Biting |

| Upper lateral incisors |

(2) |

7–8 years |

Biting |

| Lower canines |

(3) |

9–10 years |

Tearing |

| First premolars |

(4) |

10–11 years |

Chewing |

| Second premolars |

(5) |

11–12 years |

Chewing |

| Upper canines |

(3) |

11–12 years |

Tearing |

| Second molars |

(7) |

12–13 years |

Chewing |

| Third molars |

(8) |

17–24 years |

Chewing |

Table 1.4 FDI World Dental Federation notation for permanent (secondary) dentition.

| Patient’s upper right (1) |

Patient’s upper left (2) |

| 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 |

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

| 48 47 46 45 44 43 42 41 |

31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

| Patient’s lower right (4) |

Patient’s lower left (3) |

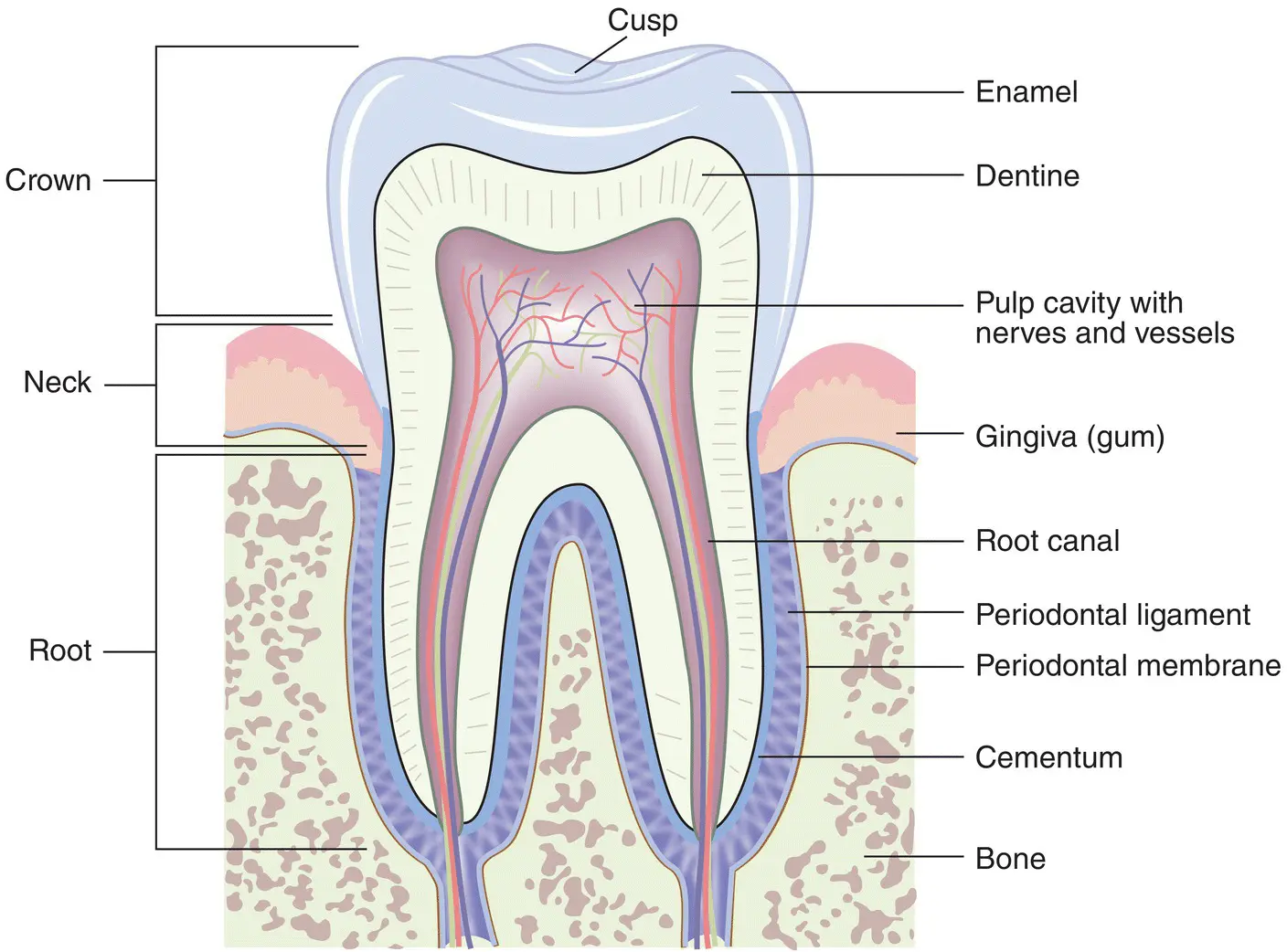

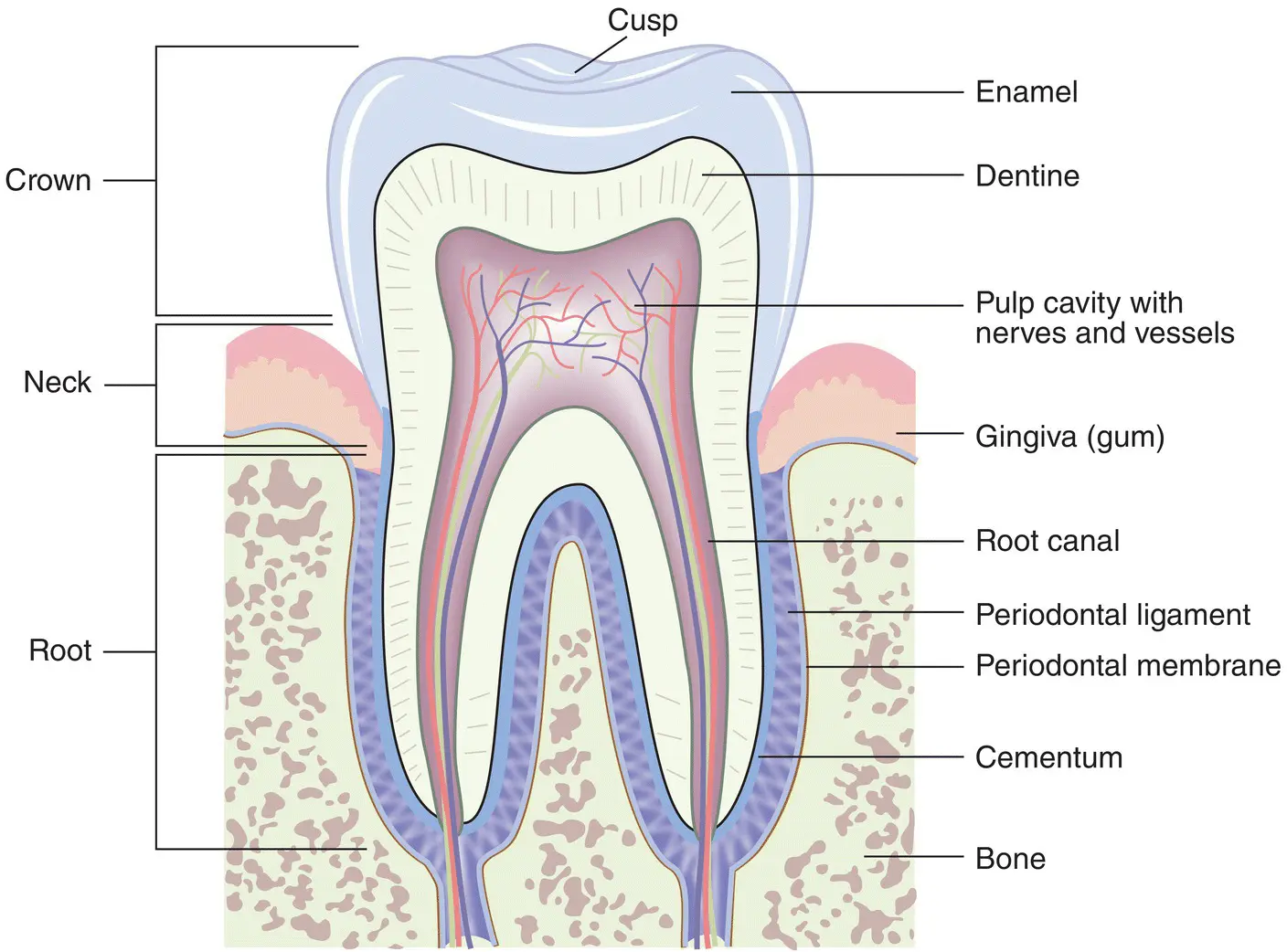

Tooth structure ( Figure 1.9) is complex and comprises several different hard layers that protect a soft, inner pulp (nerves and blood vessels).

Organic and inorganic tooth matter

The terms organic and inorganic are often mentioned in connection with tooth structure. Educators must know what these terms mean and their percentages in hard tooth structures.

Organic means living and describes the matrix (framework) of water, cells, fibres and proteins, which make the tooth a living structure.

Inorganic means non‐living and describes the mineral content of the tooth, which gives it its strength. These minerals are complex calcium salts.

Table 1.5shows the percentages of organic and inorganic matter in hard tooth structures.

It is also important to know the basic details about these three hard tooth substances, and also pulp.

Enamel ( Figure 1.9) is made up of prisms (crystals of hydroxyapatite) arranged vertically in a wavy pattern, which give it great strength. The prisms, which resemble fish scales, are supported by a matrix of organic material including keratinised ( horn‐like ) cells, which can be seen under an electron microscope.

Figure 1.9 Structure of the tooth.

Source: From [1]. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Table 1.5 Percentages of organic and inorganic matter in hard tooth structures.

| Structure |

Inorganic |

Organic |

| Enamel |

96% |

4% |

| Dentine |

70% |

30% |

| Cementum |

45% |

55% |

Enamel is:

The hardest substance in the human body.

Brittle – it fractures when the underlying dentine is weakened by decay (caries).

Insensitive to stimuli (e.g. hot, cold, and sweet substances).

Darkens slightly with age – as secondary dentine is laid down and stains from proteins in the diet, tannin‐rich food and drinks, and smoking are absorbed.

Enamel is also subject to three types of wear and tear (see Chapter 6). The educator

needs to be aware of these and able to differentiate between them:

1 Erosion – usually seen on palatal and lingual (next to palate and tongue) surfaces.

2 Abrasion – usually seen on cervical (outer neck of tooth) surfaces.

3 Attrition – natural wear often seen on occlusal (biting) surfaces.

Dentine constitutes the main bulk of the tooth ( Figure 1.9) and consists of millions of microscopic tubules (fine tubes), running in a curved pattern from the pulp to the enamel on the crown and the cementum on the root.

Читать дальше