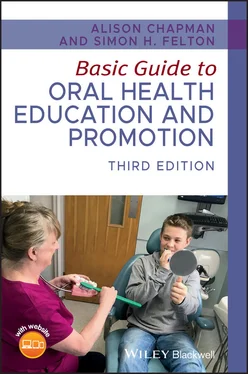

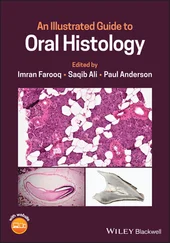

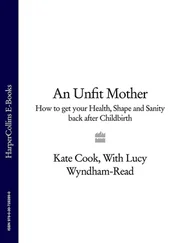

Before oral health educators (OHEs) can deliver dental health messages to patients and confidently discuss oral care and disease with them, they will need a basic understanding of how the mouth develops in utero (in the uterus), the anatomy of the oral cavity ( Figures 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4), and how the following structures function within it:

Teeth (including dentition).

Periodontium (the supporting structure of the tooth).

Tongue.

Salivary glands (and saliva).

Figure 1.1 Structure of the oral cavity.

Source: From [1]. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Figure 1.2 A healthy mouth (white person).

Source: [2]. Reproduced with permission of Blackwell.

Figure 1.3 A healthy mouth (black person).

Source: Alison Chapman.

Figure 1.4 A healthy mouth (Asian person).

Source: Alison Chapman.

A basic understanding of the development of the face, oral cavity, and jaws in the embryo and developing foetus will help enable the OHE to discuss with patients certain oral manifestations of conditions that stem from in utero development; notably cleft lip and palate.

An embryo describes the growing organism up to 8 weeks in utero ; a foetus describes the growing organism from 8 weeks in utero .

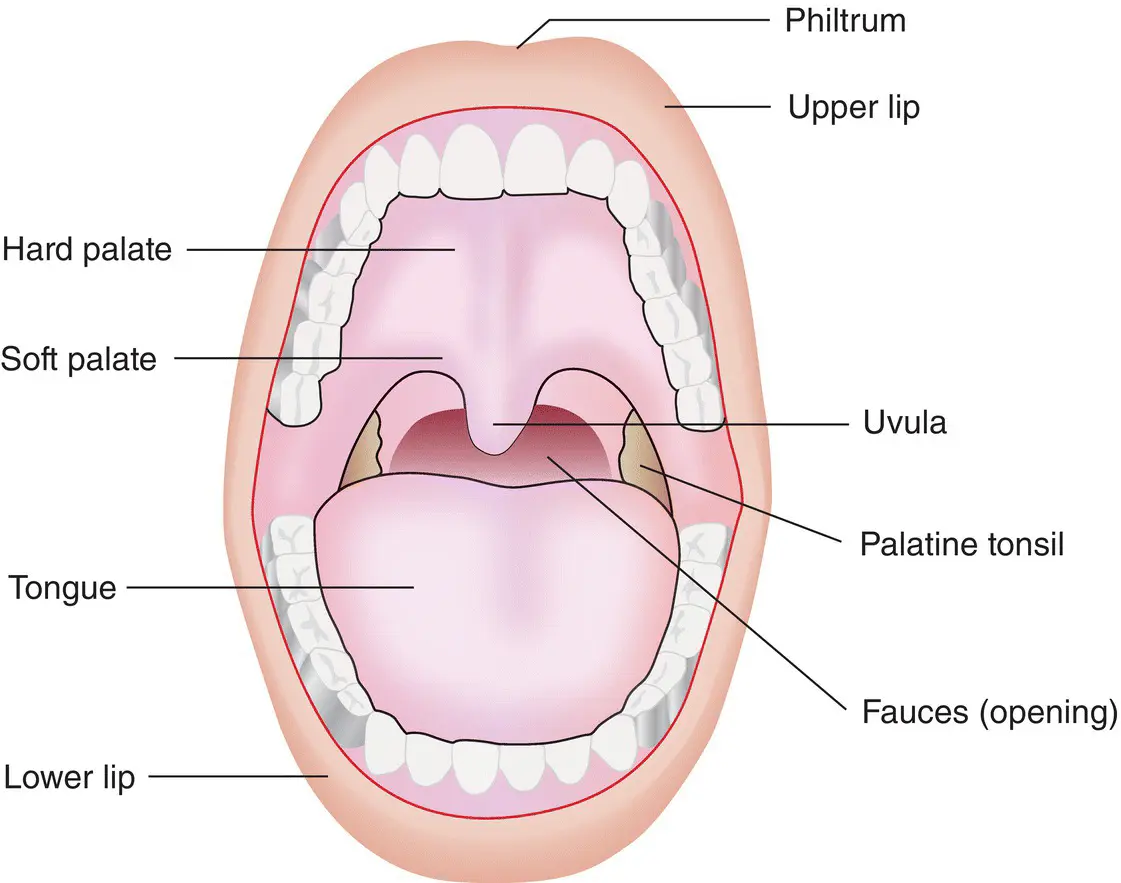

At approximately week 4 in utero ( Figure 1.5), the embryo begins to develop five facial processes (or projections), which eventually form the face, oral cavity, palate, and jaws by week 8 [3]:

Frontonasal process – forms the forehead, nose, and philtrum (groove in upper lip).

Maxillary process (two projections) – forms the middle face and upper lip.

Mandibular process (two projections) – forms the mandible (lower jaw) and lower lip.

Figure 1.5 Facial development at 4 weeks in utero .

Source: From [3]. Reproduced with permission of Wiley‐Blackwell.

Development of the palate and nasal cavities

Week 5

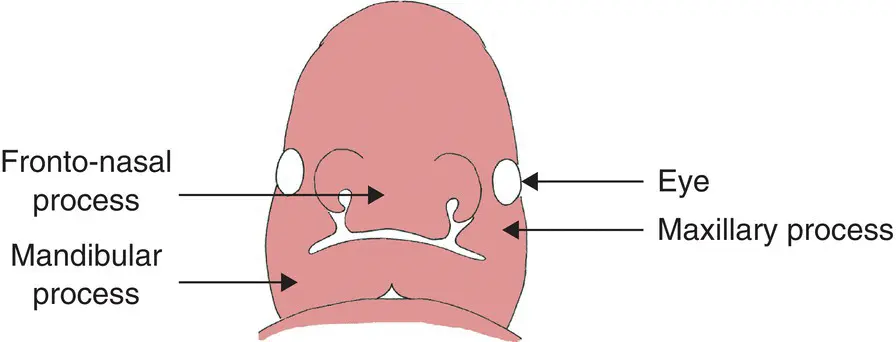

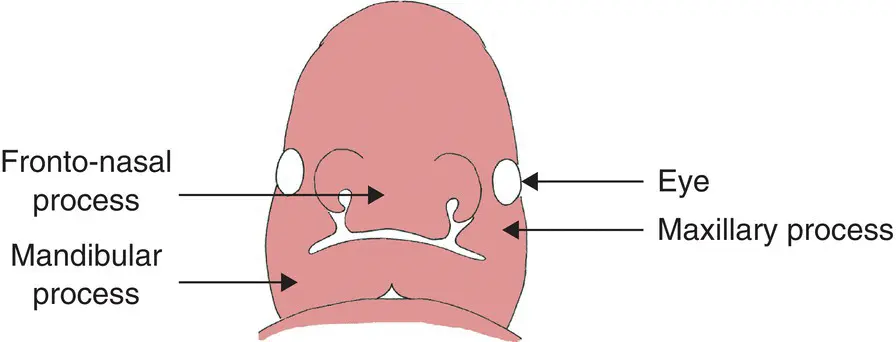

The frontonasal and maxillary processes begin to form the nose and maxilla (upper jaw). However, if the nasal and maxillary processes fail to fuse, then a cleft will result. This is the most common craniofacial (skull and face) abnormality that babies are born with, and is thought to commonly result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors, or as part of a wider syndrome [4].

A baby can be born with a cleft lip, a cleft palate, or both. Cleft lip and/or palate occurs in 1–2 births out of every 1000 in developed countries [5]. Submucous cleft palate can also occur, which is a cleft in the soft palate and includes a split in the uvula. Surgery to close a gap is often undertaken when a baby is less than a year old.

A cleft lip can be anything from a small notch in the lip (incomplete cleft lip) to a wide gap that runs up to the nostril (complete cleft lip). It can also affect the gum, which, again, can be a small notch or complete separation of the gum.

A cleft lip can be either ( Figure 1.6):

Unilateral – affects one side of the mouth (incomplete or complete).

Bilateral – affects both sides of the mouth (incomplete or complete).

A cleft palate is a gap in the roof of the mouth. A cleft can affect the soft palate (towards the throat) or the hard palate (towards the lips), or both. Like a cleft lip, a cleft palate can be unilateral or bilateral, and complete or incomplete ( Figure 1.6)

By week 6, the primary palate and nasal septum have developed. The septum divides the nasal cavity into two.

By week 8, the palate is divided into oral and nasal cavities.

Development of the jaws (mandible and maxilla)

Week 6

By week 6, a band of dense fibrous tissue (Meckel’s cartilage) forms and provides the structure around which the mandible forms.

By week 7, bone develops, outlining the body of the mandible.

As the bone grows backwards two secondary cartilages develop; these eventually become the condyle and coronoid processes.

As the bone grows forward, the two sides are separated by a cartilage called the mandibular symphysis. The two sides will finally fuse into one bone approximately 2 years after birth.

Figure 1.6 Cleft lip and palate in a six‐month‐old baby.

Source: Dreamstime.com/PattarawitChompipat | ID 84347343. Reproduced with permission of Dreamstime.com.

Upward growth of bone begins along the mandibular arch forming the alveolar process, which will go on to surround the developing tooth germs.

By week 8, ossification (bone development) of the maxilla begins.

Tooth germ development in the foetus

Tooth germ (tissue mass) develops in three stages known as bud, cap, and bell. The developing tooth germ can be affected by the mother’s health (see Chapter 20).

1 Bud – at 8 weeks, clumps of cells form swellings called enamel organs. Each enamel organ is responsible for the development of a tooth.

2 Cap – the enamel organ continues to grow and by 12 weeks (the late cap stage), cells have formed the inner enamel epithelium and the outer enamel epithelium. Beneath the inner enamel epithelium, the concentration of cells will eventually become the pulp. The enamel organ is surrounded by a fibrous capsule (the dental follicle), which will eventually form the periodontal ligament.

3 Bell – by 14 weeks, the enamel organ will comprise different layers, which will continue to develop to form the various parts of the tooth.

MAIN FUNCTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY

The oral cavity is uniquely designed to carry out two main functions:

1 Begin the process of digestion. The cavity’s hard and soft tissues, lubricated by saliva, are designed to withstand the stresses of:

Biting.

Chewing.

Swallowing.

1 Produce speech.

Different types of teeth are designed (shaped) to carry out different functions. For example, canines are sharp and pointed for gripping and tearing food, while molars have flatter surfaces for chewing. Tooth form in relation to function is called morphology.

Dental nurses and healthcare workers may remember from their elementary studies that there are two types of dentition (a term used to describe the type, number and arrangement of natural teeth):

Читать дальше