Enzymes and toxins (produced by bacteria).

Lactic acid.

Mineral salts.

Stages in plaque formation

Stage 1

Saliva plays a large part in the formation of plaque, and within a few minutes of cleaning, the tooth is covered in a sticky film made from salivary proteins, called the salivary pellicle. This provides receptors for early bacterial colonisers to attach to. Initially, these connections are weak and easily broken. These early aerobic bacteria are gram‐positive (stain violet when exposed to Gram’s stain in the laboratory), and feed on sugars from the diet.

Bacteria begin to produce substances that anchor them to the pellicle, thus increasing the adhesive properties of plaque. The matrix builds, with some matrix components made by bacteria themselves.

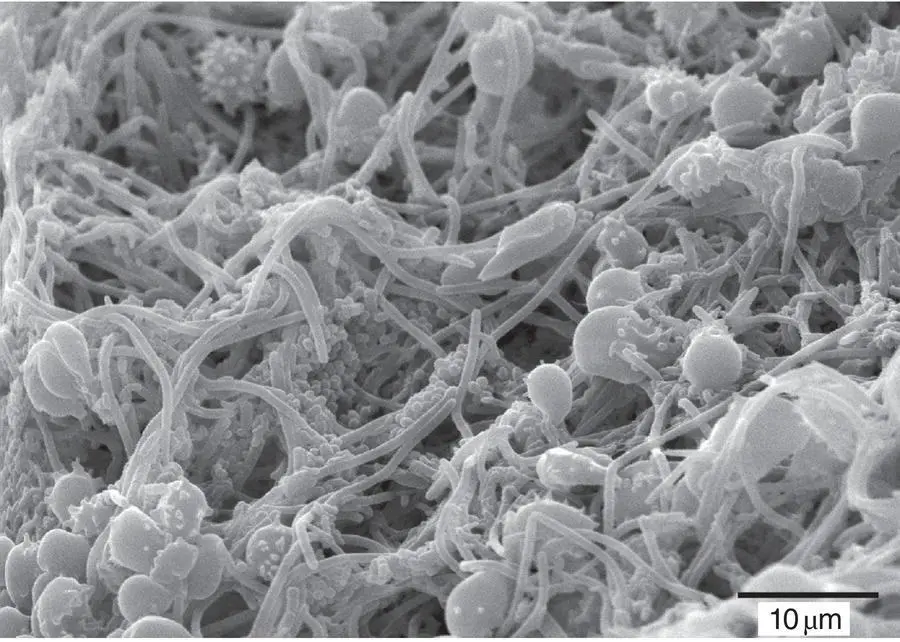

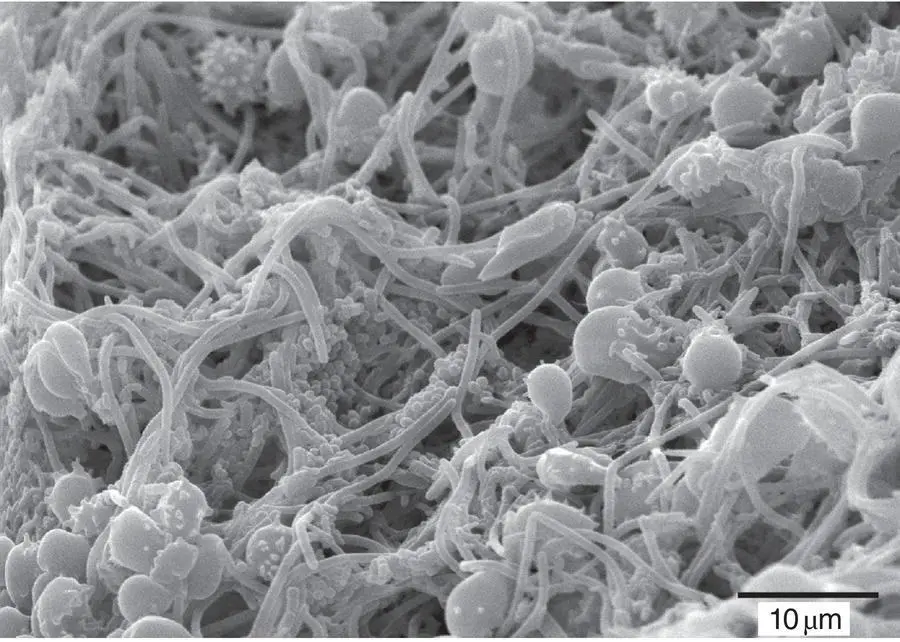

Bacteria begin to produce carbon dioxide and also excrete waste products. The environment becomes more attractive to gram‐negative species (which stain red when exposed to Gram’s stain). The plaque becomes thicker and denser as it matures, and contains diverse species that have a potential to cause disease. Mushroom‐shaped ‘clouds’ of matrix form with channels running between them to facilitate the movement of nutrients and waste products ( Figure 2.3).

As the biofilm thickens, some bacteria start to die or break off to form new colonies. Bacteria within the colony reproduce to replace those that have broken away or died, and the cycle continues.

Figure 2.3 Mature plaque (scanning electron microscope).

Source: Dr Rachel Sammons. Reproduced with permission of Institute of Clinical Sciences, College of Medical & Dental Sciences, The University of Birmingham.

Local risk factors in the retention of plaque

The importance of the following local risk factors in the retention of plaque (and therefore in the development of dental disease) should not be underestimated:

Large or uneven restorations.

Bridges.

Crowns with poor margins.

Implants.

Dentures and obturators.

Orthodontic appliances.

Calculus.

Periodontal pockets.

The following measures should be taken to prevent the build‐up of plaque:

Physical (i.e. toothbrushing and interdental cleaning).

Chemical (e.g. chlorhexidine mouthwashes) – not needed by all patients.

A low sucrose diet.

Remember!The enzymes and toxins of anaerobic bacteria in mature plaque are the primary causes of gingivitis, which can lead to periodontitis. It is therefore vital that the patient removes plaque in order to prevent the onset of these more serious conditions.

Calculus is a mineralised hard deposit of calcium salts that forms in plaque. It is found on teeth and other solid structures in the mouth and plays a role in the development of periodontal disease by attracting more plaque.

Patients sometimes refer to calculus (a Latin word meaning stone ) as tartar or scale . When talking to patients, it is worth mentioning that these three terms mean the same thing. Some patients get confused between plaque and calculus and think that they are one and the same, and so the differences between them should be explained in simple terms. Other patients know what calculus looks like and complain of its build‐up around the lower incisors.

Calculus consists of approximately:

70% inorganic salts.

30% microorganisms and organic materials.

There are two main types of calculus:

1 Supragingival – which forms above the gingival margin.

2 Subgingival – which forms in the periodontal pocket.

Supragingival calculus ( Figure 2.4) begins to form after 2–14 days of inadequate plaque removal, depending upon the individual’s cleaning ability and mineral content of their saliva. Most supragingival calculus is found on teeth adjacent to the main saliva ducts, i.e. behind the lower central incisors and on the buccal (cheek) surfaces of the upper first and second molars.

Figure 2.4 Supragingival calculus before (right) and after (left) scaling.

Source: Mary Mowbray. Reproduced with permission of Mary Mowbray.

Supragingival calculus is usually preceded by plaque accumulation that becomes hardened (calcified) by the mineral salts in saliva (i.e. calcium and phosphate salts become incorporated into sticky plaque, causing calcification).

Some patients have more supragingival calculus than others, and this is because they:

Have relatively more calcium and phosphate ions in saliva, and/or

Do not remove plaque effectively, and so there is a material present for saliva to calcify.

Have highly alkaline saliva, which favours the production of calculus.

Patients cannot remove calculus with a brush or floss once it has hardened, and because it has a rough texture, more plaque adheres, and the process of calcification begins again. Dentists and hygienists scale and polish teeth to remove supragingival calculus (and help prevent periodontal disease).

Subgingival calculus ( Figure 2.5) is less obvious to the patient, and is found below the gum margin in periodontal pockets. It is often black, dark brown or green in colour and is formed when minerals from fluid (crevicular fluid) in the gingival crevice come into contact with plaque. (The dark colour is derived from the breakdown of blood constituents resulting from ulceration in the crevice.)

Subgingival calculus is often hard and difficult to remove. Its presence is much more significant than supragingival deposits as it indicates that periodontitis is present.

Figure 2.5 Subgingival calculus exposed after improved oral hygiene.

Source: Mary Mowbray. Reproduced with permission of Mary Mowbray.

There are two types of staining that can affect the tooth:

Intrinsic.

Extrinsic.

Intrinsic staining occurs within the tooth structure during its development (before birth, or during early childhood), and before it erupts (except in cases of pulpal death, usually caused by trauma). Intrinsic stains cannot be removed, although tooth whitening can conceal them. The whitened tooth will continue to darken with age, but the whitening process can be topped up so that intrinsic stains remain concealed.

Causes of intrinsic staining include:

Tetracycline – an antibiotic. Taken by a baby or young child, or passed to the foetus by pregnant mother (white, yellow, brown, and grey colours). Not recommended for children under 12 years old or pregnant women.

Fluoride taken in excess – from tablets, swallowing toothpaste, and naturally occurring high levels in water supply. This is called fluorosis (see Chapter 11).

Systemic (whole body) upset. Premature birth, acute illness of a baby, young child or pregnant mother can cause hypoplasia – the underdevelopment of a tooth, and therefore enamel (see Chapter 8).

Читать дальше