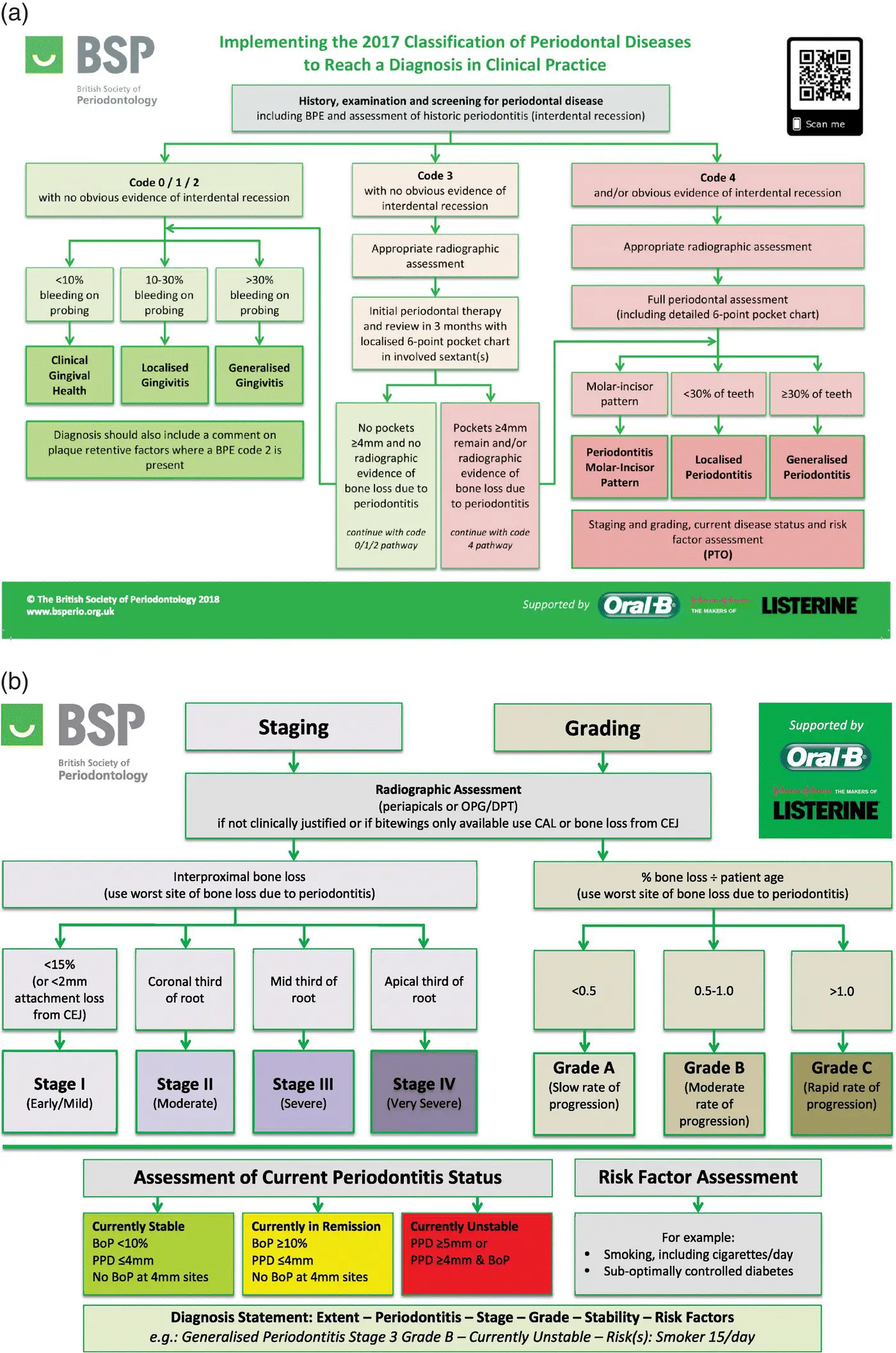

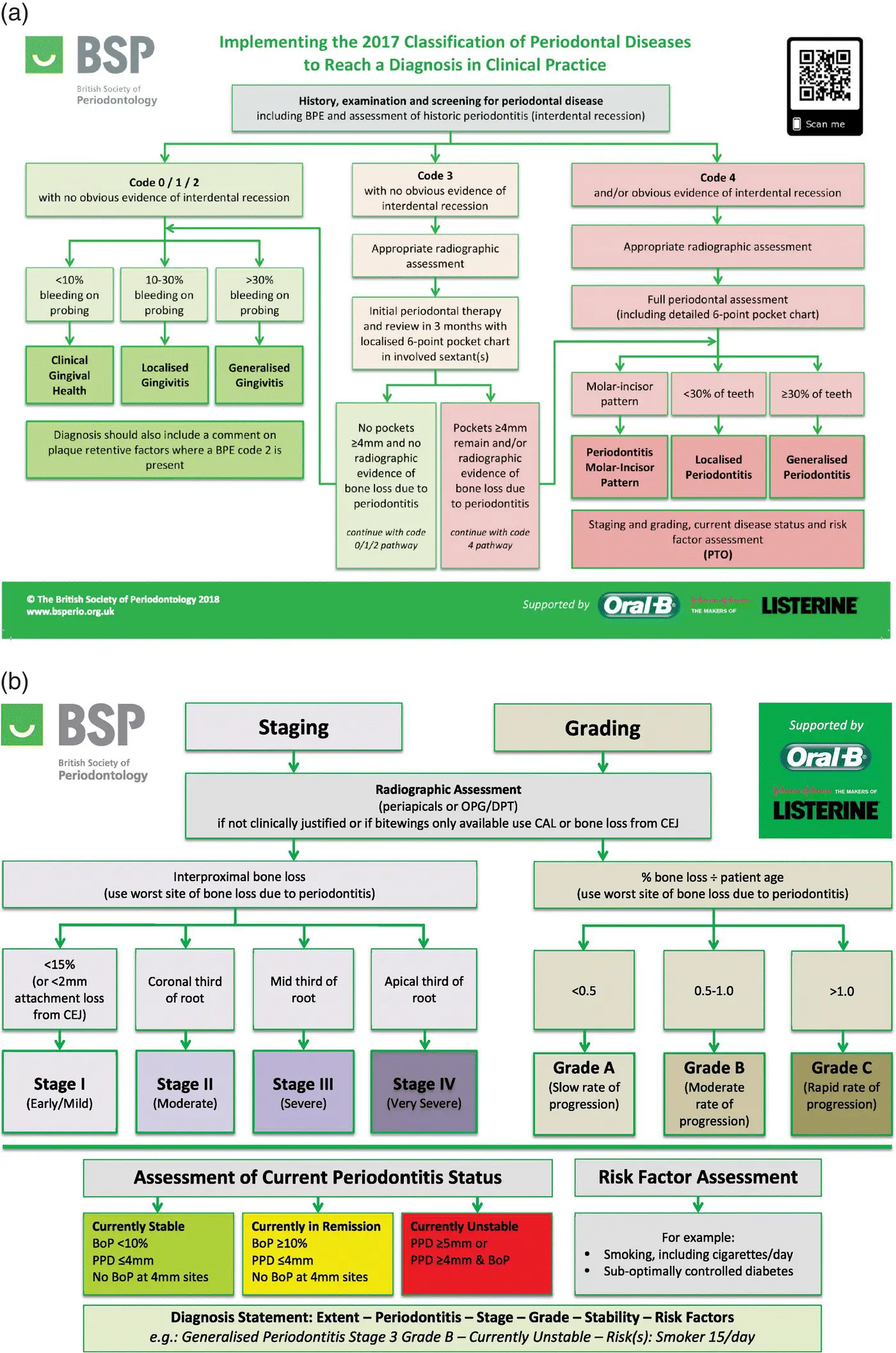

Extent – localised or generalised.

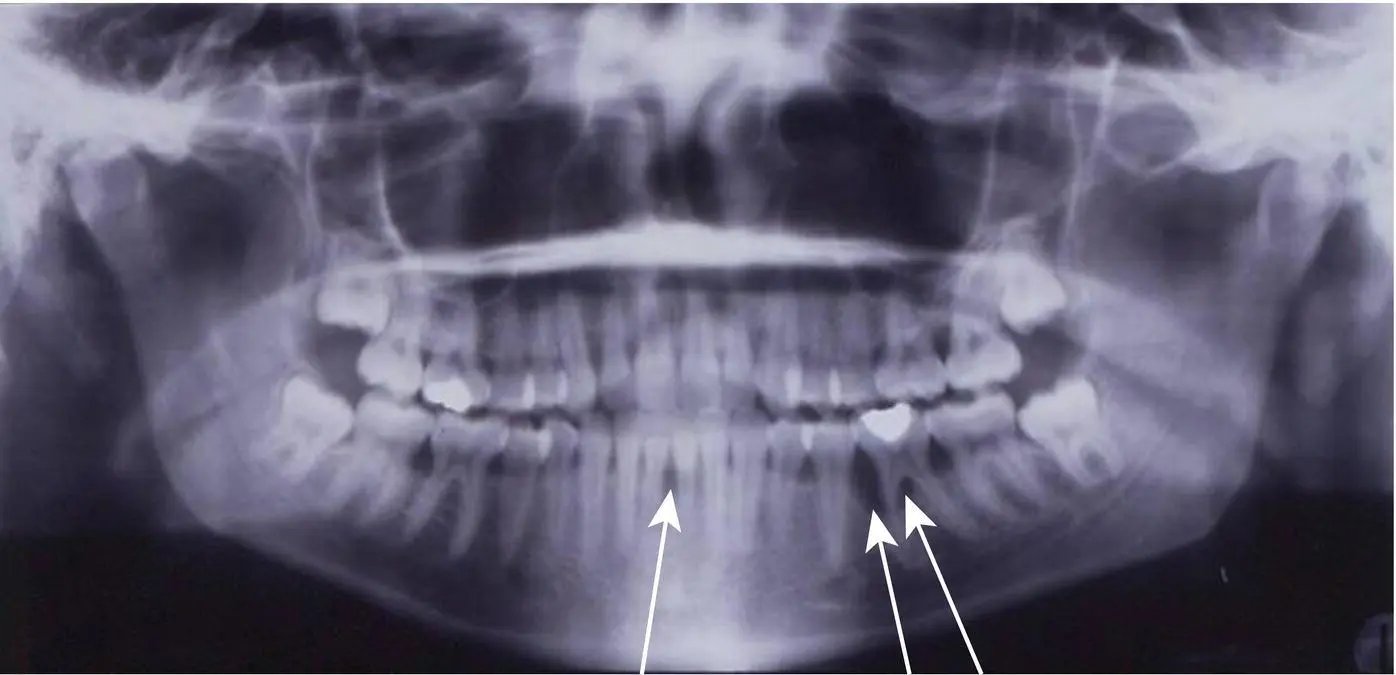

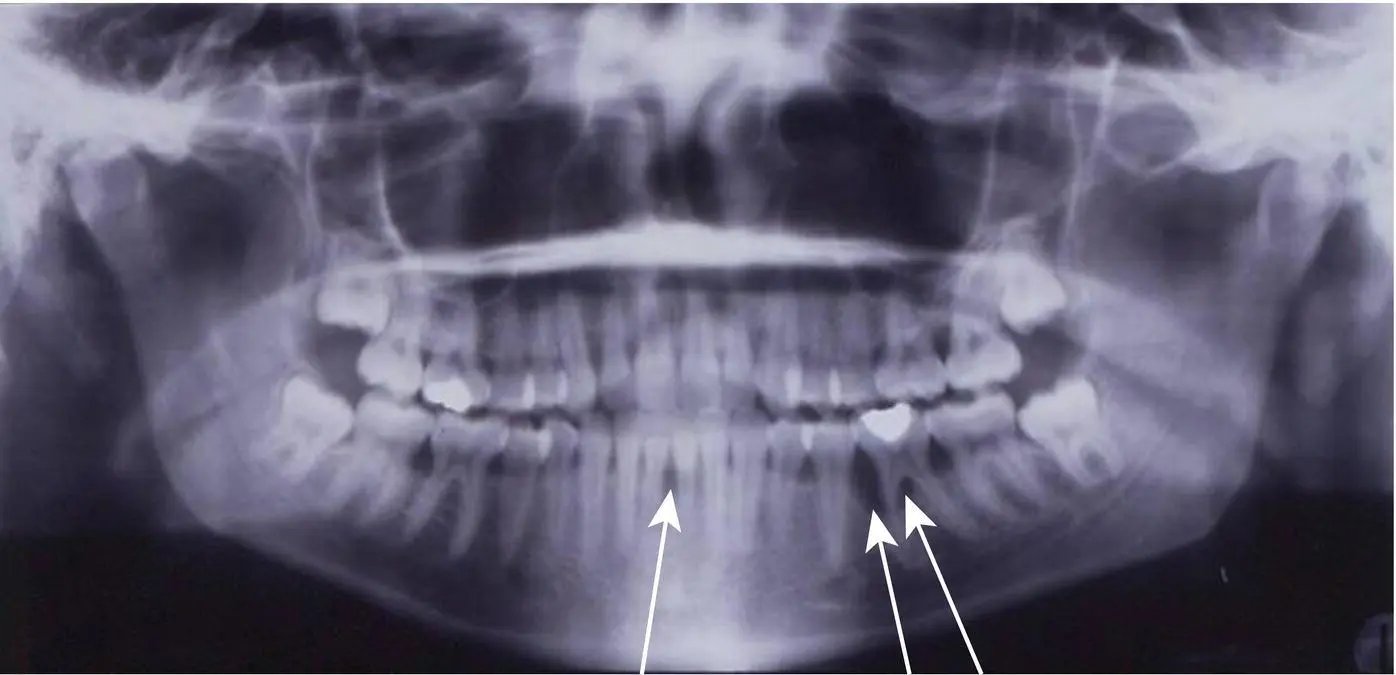

Stage – ranging from stage I (early, mild) to stage IV (severe) using X‐rays to measure the extent of interdental bone loss on the worst site ( Figure 4.6).

Grade – A, B, or C. Dividing the percentage of bone loss at the worst site due to periodontitis by the patient’s age to determine the rate of progression of the disease.

Current status of the disease – stable, in remission, or unstable.

Risk factors – e.g. smoking, medically compromised.

NECROTISING ULCERATIVE GINGIVITIS

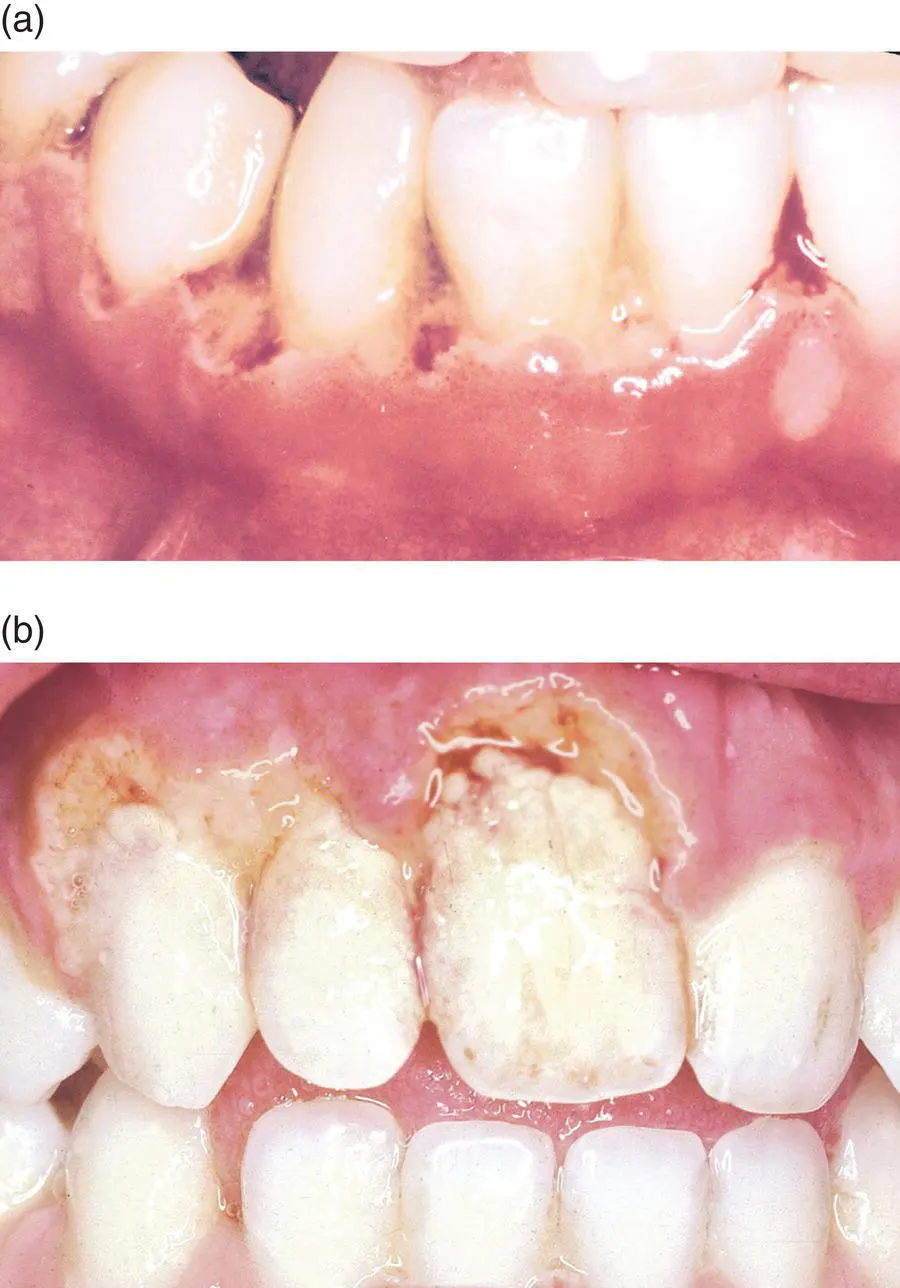

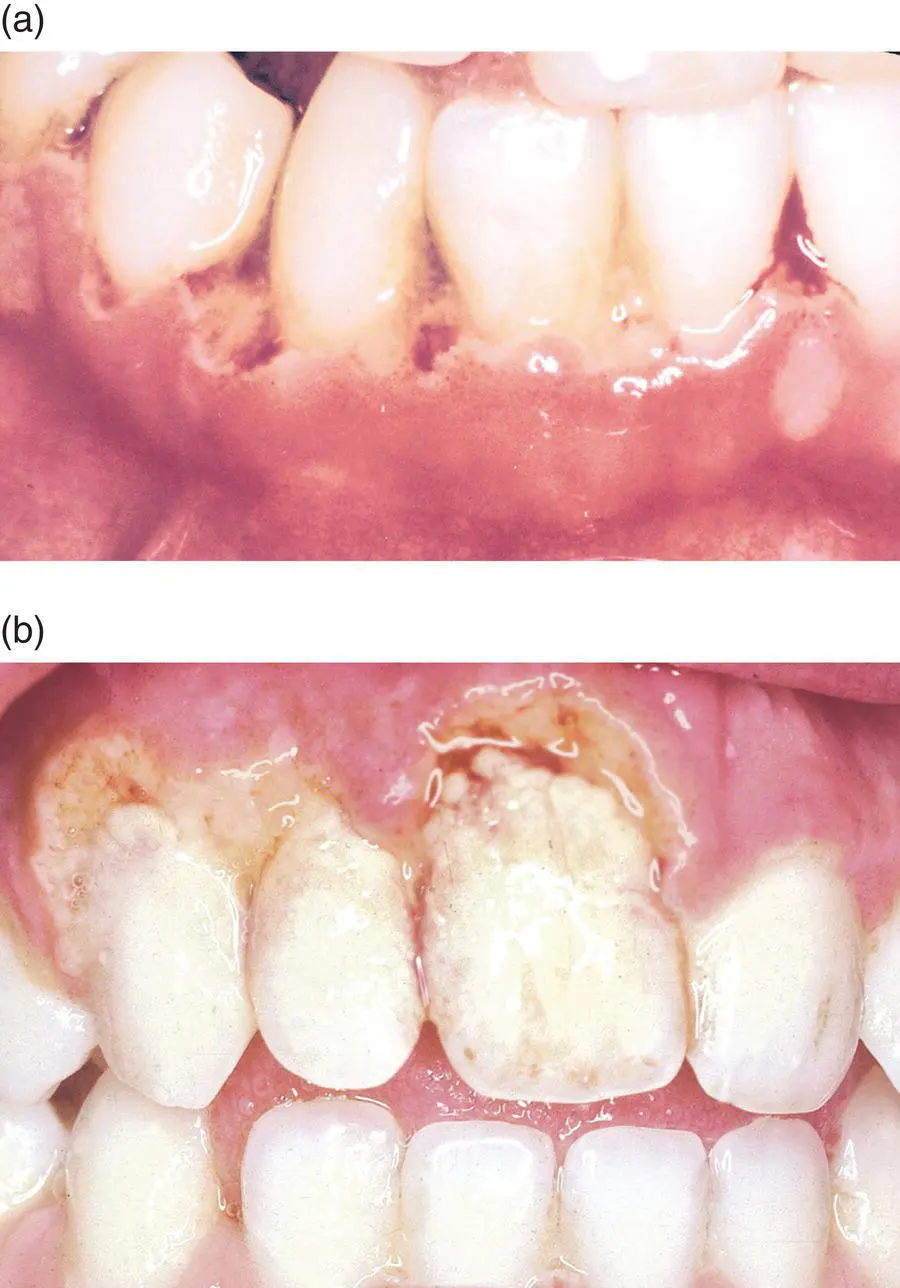

Necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) ( Figure 4.7a,b), also known as acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG), trench mouth, or Vincent’s angina , is one of the most unpleasant acute illnesses to affect the oral cavity, and can make a patient feel extremely ill.

Figure 4.5 (a,b)Implementing the 2017 Classification of Periodontal Diseases to Reach a Diagnosis in Clinical Practice.

Source: From [6]. Reproduced with permission of The British Society of Periodontology.

Figure 4.6 25‐year‐old woman; localised periodontitis, stage III (severe), grade‐C, currently unstable, no risk factors.

Source: Professor Nicola West, Bristol University. Reproduced with permission of Professor Nicola West.

Figure 4.7 (a,b)Necrotising ulcerative gingivitis.

Source: [7]. Reproduced with permission of Blackwell.

Causes of NUG are not fully understood – various microorganisms are involved, mainly anaerobic bacteria – the principle bacterium being Treponema denticola , which is capable of invading oral tissues [4].

NUG was common in the trenches during the First World War (hence the term trench mouth) and, although not contagious, tends to occur in communities where resistance is weak due to ill health or poor environmental conditions and nutrition.

Today, NUG is most commonly found in young adults between 18–25 years old, and often associated with students who have recently moved away from home and have started to look after themselves.

Predisposing factors include:

Poor oral hygiene.

Poor diet.

Smoking.

Immune system deficiency, such as HIV/AIDS.

Stress/fatigue.

Clinical features of NUG include:

Sudden onset and rapid development.

Painfully inflamed gingivae and ragged, sloughing ulcers as bacteria invade the tissues.

Acute inflammation and bleeding.

Halitosis. Patients often complain of a metallic taste.

Swollen glands, temperature, and general malaise.

Destruction of tissues when no treatment is available – patients who have repeated attacks often exhibit permanent loss of interdental papillae.

Treatment of NUG depends on its severity, but should be rapid to prevent the destruction of the interdental papillae, and includes:

Stopping smoking and using recreational drugs (if applicable).

Scaling – as soon as possible (on the first visit). An ultrasonic scaler makes the process quicker, gentler, and more tolerable for the patient.

Hydrogen peroxide mouthwash – due to its mechanical cleaning properties and its ability to release oxygen into the area, killing the anaerobic bacteria.

Chlorhexidine mouthwash – effective in reducing plaque formation as the patient may find it too painful to clean mechanically.

Antibiotics (metronidazole, tetracycline) – if the patient shows signs of being generally ill with fever or severe lymph gland involvement.

Emphasis on excellent oral hygiene.

Reducing stress levels, regular rest.

A healthy well‐balanced diet (see Chapter 9).

Regular dental appointments to treat and monitor the condition.

PERI‐IMPLANT MUCOSITIS AND PERI‐IMPLANTITIS

Peri‐implant mucositis is a reversible inflammatory reaction causing redness and swelling localised to the soft tissue around implants.

Dental implants are used to replace missing teeth either on their own, as part of a bridge, or as an attachment for a denture. Modern implants have been used in dentistry since the 1960s (and are also used in other areas of the body for attaching prosthesis, such as in the ear).

The dental implant consists of a titanium screw placed in the bone of the maxilla or mandible, which is then left for up to six months to integrate with the bone before the final restoration is attached to it. They can be used to replace one tooth, as part of a bridge, or the foundation for a denture that either clips to the implant or is permanently placed. When designing the restoration, the ability to clean thoroughly around it should be considered as they can fail if excellent oral hygiene is not maintained.

The area around the junction between the implant and restoration is subject to gingival inflammation and bone loss just like a natural tooth with plaque and calculus accumulation. The depth of the gingival sulcus (gingival crevice) is deeper than that of a natural tooth and can be 3–4 mm.

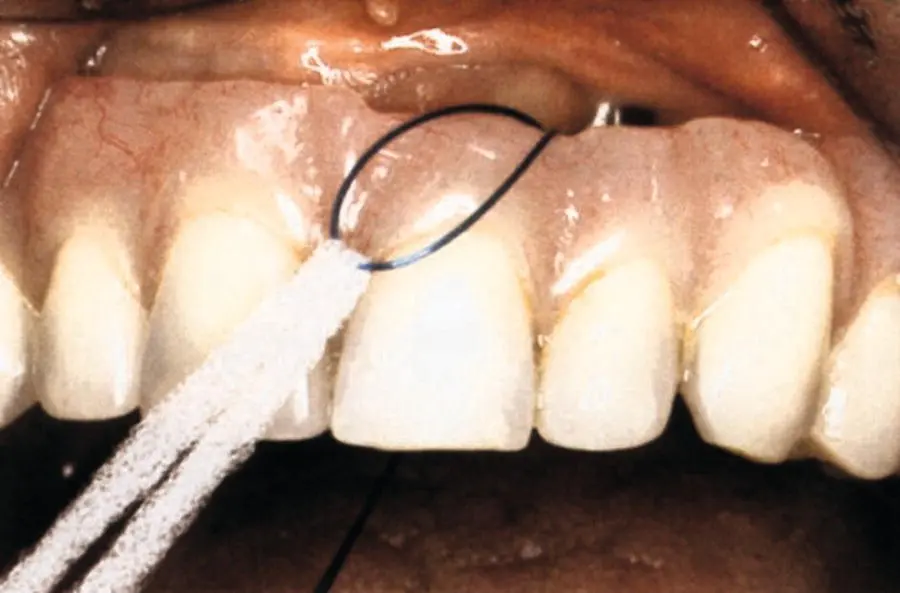

Similar to gingivitis progressing to periodontitis, peri‐implant mucositis can progress to peri‐implantitis, which involves destruction of the bone ( Figures 4.8, 4.9). The tissues around the implant should look similar to that of a natural tooth: pink, firm and stippled.

The patient should have regular dentist or hygienist appointments to assess, as early intervention in the event of a problem is important to prevent failure of the implant.

Oral hygiene aids for peri‐implant mucositis and peri‐implantitis

When advising patients on oral hygiene techniques, the depth of the sulcus must be taken into consideration.

Figure 4.8 Peri‐implantitis.

Source: Alison Chapman.

Figure 4.9 Peri‐implantitis, surgically exposed.

Source: Alison Chapman.

Figure 4.10 A single tufted or interspace brush, fixed lower.

Source: Mary Mowbray. Reproduced with permission of Mary Mowbray.

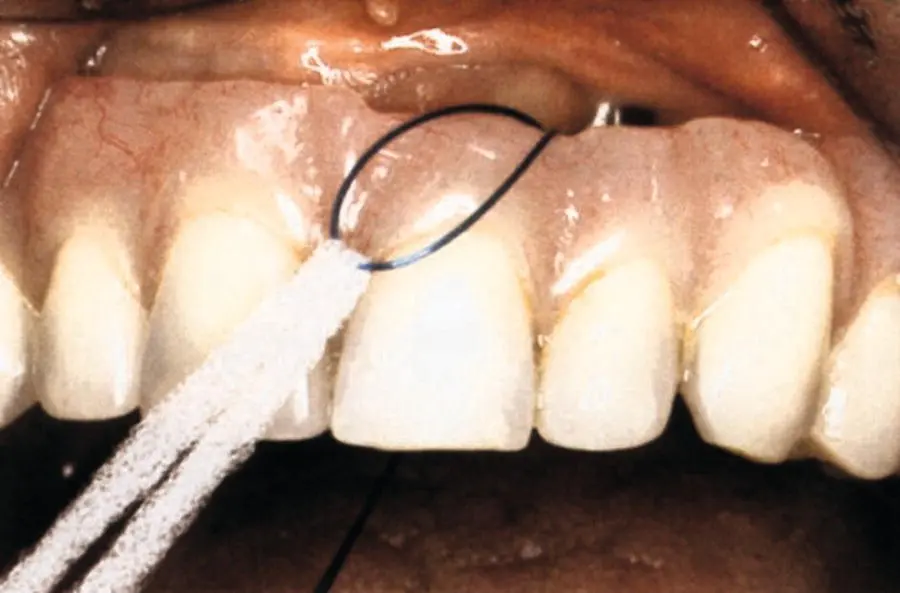

Figure 4.11 Floss threader on a fixed bridge.

Source: Mary Mowbray. Reproduced with permission of Mary Mowbray.

Figure 4.12 (a,b)Oral‐B® SuperFloss™ with a fixed mix bridge (a) and fixed bridge (b).

Читать дальше