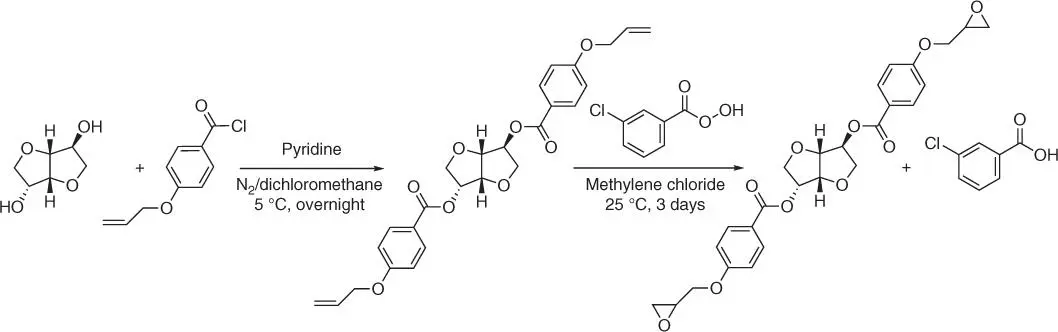

The next stage of the reaction is carried out using the meta ‐chloroperbenzoic acid, as described above.

The synthesis of isosorbide‐based epoxy resins using epichlorohydrin ( Figure 1.43) can be accomplished in a different manner. Isosorbide can be reacted with a large excess (even a 10‐fold) of epichlorohydrin in the presence of strong alkali–sodium hydroxide (40% aq. solution) in a single‐stage reactor with continuous removal of water [125]. The reaction is carried out at a temperature of 109–115 °C for eight hours and the product with an epoxy value of 0.451–0.467 mol/100 g is obtained. In another method, sodium hydride as a base in diglyme is used to prepare the disodium salt of isosorbide (reaction time about six hours at a temperature of 43–48 °C and then one hour at a temperature of 85 °C) [126], which is then reacted with nearly 20‐fold excess of epichlorohydrin (six hours of dropwise addition, leaving overnight at room temperature, and heating for 2.5 hours at a temperature of 55 °C). The resulted product is obtained with an epoxy value of 0.359 mol/100 g. Sodium hydroxide (50% aq. solution) can be used instead of sodium hydride [127], also in the two‐step method. The disodium salt of isosorbide synthesis is catalyzed by trimethylcetylammonium bromide. In the second step, the disodium salt is reacted with the 10‐fold excess of epichlorohydrin in the presence of another phase transfer catalyst – tetrabutylammonium bromide (heating at a temperature of 115 °C for about three hours is carried out). The obtained isosorbide‐based epoxy resin has an epoxy value of 0.518 mol/100 g.

It is also possible to react isosorbide with epichlorohydrin in a two‐stage process under different conditions [128]: using an aqueous alkali (mostly sodium/potassium hydroxide) and an organic solvent (toluene and dimethyl acetamide) or the first stage is carried out in the presence of the Lewis acid catalyst (stannous fluoride).

The cross‐linked bio‐based epoxy resin (an epoxy value of 0.440 mol/100 g), synthesized in the one‐step reaction from isosorbide and epichlorohydrin [129] in the presence of 50% aqueous NaOH, exhibits properties comparable to those of the commercial bisphenol A‐based resin Epidian 5 (an epoxy value of 0.510 mol/100 g). Depending on the cross‐linking agent used (triethylenetetramine, isophoronediamine, tetrahydrophthalic, and phthalic anhydrides), the selected mechanical properties of the isosorbide‐based resin are in some cases even better (the flexural and compression strengths and the Brinell hardness). Also, the Izod impact strength of this resin is usually better than that of the cross‐linked resin Epidian 5 (even more than four times). Water sorption of the isosorbide‐based resin is much higher than that of the bisphenol‐A‐based resin (for the sample cross‐linked with triethylenetetramine, even their disintegration is observed), and as a result, the chemical resistance is less than that for the resin Epidian 5.

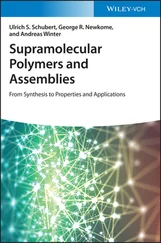

Figure 1.45 Synthesis of isosorbide diglycidyl ether using 4‐allyoxybenzoly chloride.

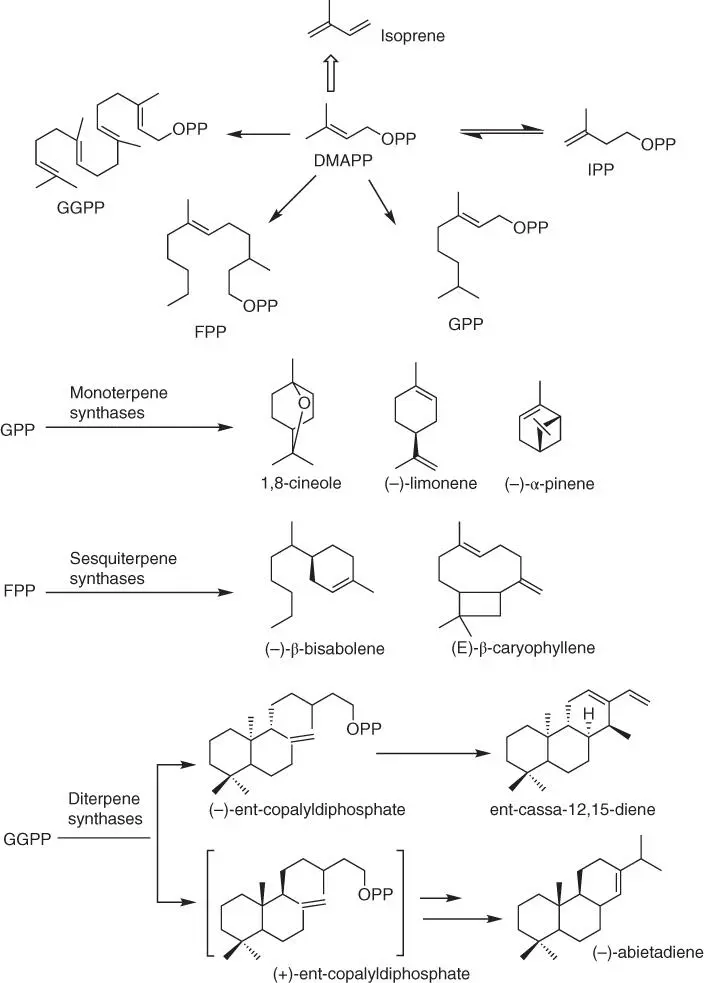

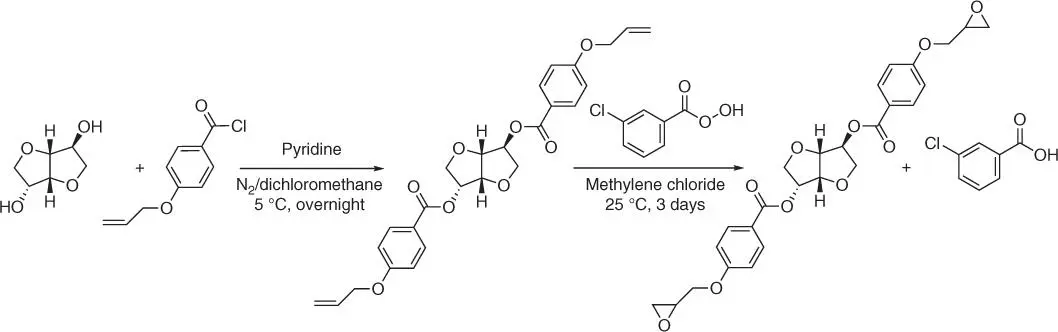

Figure 1.46 Formation of plant terpenes.

1.3.5 Terpene Derivatives

Terpenes and terpenoids are an interesting group of natural resources, with relatively large potentials as substrates for the synthesis of various polymers. They are unsaturated aliphatic structures, predominantly derived from turpentine, the volatile fraction of resins exuded from conifers [130]. The C5‐units of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) are the initial substrates for the synthesis of terpenes. It is worth highlighting here that the linear prenyl diphosphates: geranyl diphosphate (GPP, C10), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20) are precursors of terpenes obtained via the biosynthesis in the presence of prenyltransferases ( Figure 1.46). Due to the fact that terpenes consist of multiple isoprene units (C 5H 8, 2‐methyl‐1,4‐butadiene), they are categorized based on the number of units into hemiterpene (one isoprene unit, C5), monoterpene (two units, C10), sesquiterpene (two units, C15), diterpene (four units, C20), and so on [131] ( Figure 1.46) [132].

Terpenes are built from a wide range of cycloaliphatic and hydrocarbon chain structures with repeating isoprenyl double bonds. Terpenoids can be viewed as modified terpenes with added, missing, or shifted methyl and oxygenated functional groups ( Figure 1.47).

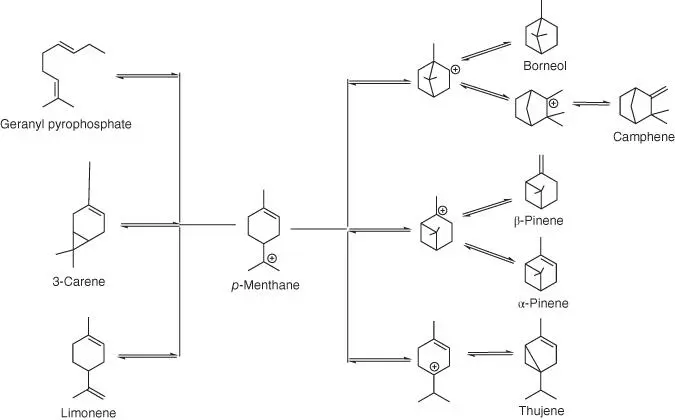

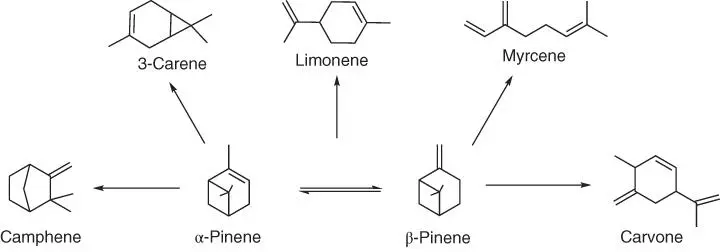

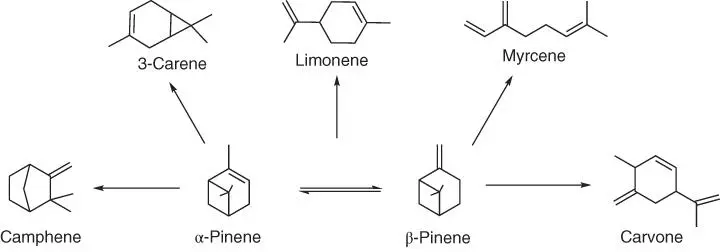

The global turpentine production is more than 300 000 tons per year, and it includes α‐pinene (45–97%) and β‐pinene (0.5–28%), with smaller amounts of other monoterpenes [130]. The pinenes and limonenes are natural chemical precursors to a wide variety of compounds used in the pharmaceutical, fragrance, and flavor industry. Pinenes, additionally, are a source of other less common terpenes ( Figure 1.48).

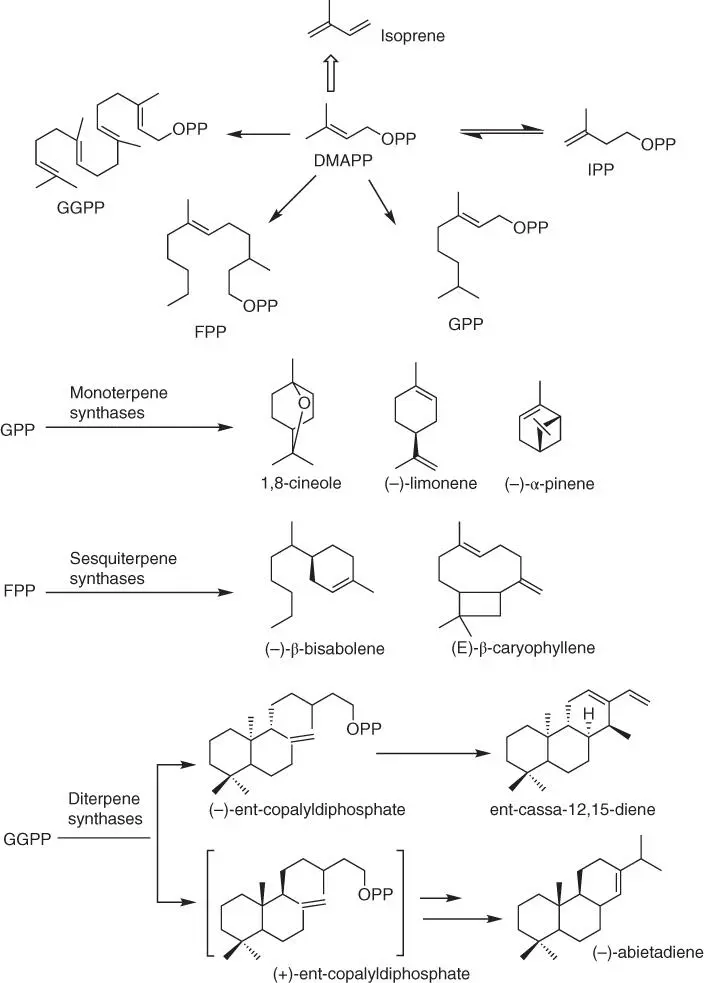

Figure 1.47 Outline of the biosynthetic pathway leading to the major monoterpenes from a single precursor.

Figure 1.48 Isomerization and oxidation processes for converting pinenes into other terpenes and a terpenoid.

Figure 1.49 Mechanism of the cationic polymerization of β‐pinene.

A methyl group or other electron‐donating groups on the double bond present within the structure of compounds obtained via the isomerization and oxidation of pinenes makes them susceptible for cationic polymerization. However, because of the presence of highly reactive exo ‐methylene double bond within the β‐pinene structure, most of the polymerization reactions involve β‐pinene, not α‐pinene ( Figure 1.49).

Some cationic polymerization of terpenes leads to oligomers or low molecular weight polymers, which along with other terpene monomers might be used for the synthesis of epoxy resins. One of the interesting applications of terpenes is the synthesis of hydrogenated terpinene‐maleic ester type epoxy resin [133]. A bio‐based epoxy resin (denoted as TME) and a waterborne dispersion of TME (denoted as WTME) obtained from the turpentine ( Figure 1.50) are nontoxic alicyclic structure epoxy resins without BPA.

The resulting film with good thermal stability and antifouling properties is transparent and flexible. However, because the obtained cured terpene‐based products are characterized by worse mechanical properties than those of BPA‐based epoxy resin, two different approaches had also been studied: (i) incorporation of cellulose nanowhiskers (CNWs) suspension, hydrolyzed from microcrystalline cellulose [134], and (ii) in combination with polyurethane [133]. In the first modification of the synthesis, the incorporation of CNWs in the WTME matrix (0.5–8 wt%) results in the increase of the storage modulus at 150 °C (from 0.8834 to 4.756 MPa), Young's modulus (from 295.6 to 800.1 MPa), and tensile strength (from 7.08 to 15.2 MPa) compared to unmodified WTME. Noted improved properties might be attributed to the formation and increase of interfacial interaction by hydrogen bonds between CNWs nanofiller and the WTME matrix. On the other hand, in the second approach ( Figure 1.51), an anionic polyol (T‐PABA) dispersion is prepared by modifying terpene‐based epoxy resin with para ‐aminobenzoic acid and then cross‐linked with a hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) tripolymer to prepare waterborne polyurethane/epoxy resin composite coating. These new cross‐linked products combine the rigidity and weatherability of the saturated terpinene alicyclic epoxy resin with the flexibility and tenacity of the polyurethane.

Читать дальше