Radiographs, the final aspect of the diagnostic procedure, provide the dentist with information to help correlate all of the facts that have been collected in listening to the patient, examining the mouth, and evaluating the diagnostic casts. The radiographs should be examined carefully for signs of caries, both on unrestored proximal surfaces and recurring around previous restorations. The presence of periapical lesions, as well as the existence and quality of previous endodontic treatments, should be noted.

General alveolar bone levels, with particular emphasis on prospective abutment teeth, should be observed. The crown-root ratio of abutment teeth can be calculated. The length, configuration, and direction of those roots should also be examined. Any widening of the periodontal membrane should be correlated with occlusal prematurities or occlusal trauma. An evaluation can be made of the thickness of the cortical plate of bone around the teeth and of the trabeculation of the bone.

The presence of retained root tips or other pathologies in the edentulous areas should be recorded. On many radiographs, it is possible to trace the outline of the soft tissue in edentulous areas so that the thickness of the soft tissue overlying the ridge can be determined.

Protection Against Infectious Diseases

Protecting against cross-contamination of patients and preventing exposure of the office staff to infectious diseases have become major concerns in dentistry in recent years. In particular, patients should be queried about a past history of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or HIV. Although AIDS has received greater publicity and generated near hysteria in the recent past, hepatitis is the major infectious occupational hazard to health care professionals. 44HCV is the most common chronic, blood-borne infection in the United States 45and is transmitted primarily through contact with blood from an infected individual.45 It has been estimated that 3.2 million Americans have been infected with HCV. 46

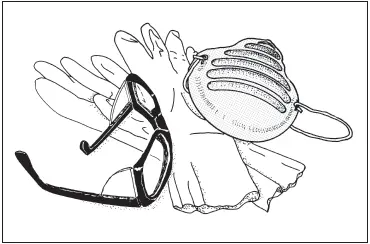

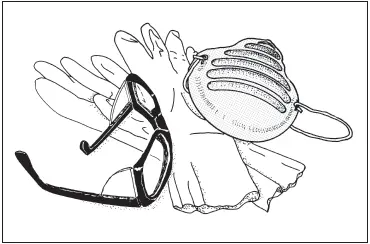

Fig 1-15Rubber gloves, a surgical mask, and eye protection are important for safeguarding dental office personnel.

There is no evidence that these diseases are contracted through casual contact with an infected person. However, the nature of dental procedures does produce the risk of contact with blood and tissues. A safe, effective vaccine against HBV is available and is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control 47–49and the ADA Council on Dental Therapeutics 50for all dental personnel who have contact with patients. There is no vaccine against HCV.

While special precautions should be taken when treating patients with a history of either disease, every patient should be treated as being potentially infectious. Rubber gloves, a surgical mask or full-length plastic face shield, protective eyeglasses (if a shield is not used), and a protective uniform are recommended for the dentist and all other office personnel who will be in contact with the patient during actual treatment ( Fig 1-15).

Concern for these matters does not end at the door to the operatory. Any item contaminated with blood or saliva in the operatory, such as an impression, is just as contaminated when it is touched outside the operatory. The specifics of decontaminating impressions are covered in chapter 17.

In addition, steps must be taken in a receiving area of the laboratory to isolate and decontaminate items coming from the dental operatory. 50An infection-control program should be established to protect laboratory personnel from infectious diseases, as well as to prevent cross-contamination that could affect a patient when an appliance returns from the laboratory to the operatory for insertion in the patient’s mouth. 51There is more to dental laboratory work than manipulating inert gypsum, wax, resins, metal, and ceramics.

1. The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms. J Prosthet Dent 2005;94: 10–92.

2. American Dental Association. Current Dental Terminology (CDT 2007–2008). Eden Prairie, MN: Ingenix, 2006:47.

3. Ciancio SC. Medications’ impact on oral health. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:1440–1448.

4. Bent S, Ko R. Commonly used herbal medications in the United States: A review. Am J Med 2004;116:478–485.

5. Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988– 2000. JAMA 2003;290:199–206.

6. Herman WW, Konzelman JL Jr, Prisant LM; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. New national guidelines on hypertension: A summary for dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:576–584.

7. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903–1913 [erratum 2003;361:1060].

8. Glick M. The new blood pressure guidelines—A digest. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:585–586.

9. Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P; American Diabetes Association. Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26(suppl 1):S80–S82.

10. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39(2 suppl 1):Sl–S266.

11. Rose LF, Mealey B, Minsk L, Cohen DW. Oral care for patients with cardiovascular disease and stroke. J Am Dent Assoc 2002; 133(suppl):37S–44S.

12. Herman WW, Konzelman JL, Sutley SH. Current perspectives on dental patients receiving coumarin anticoagulant therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 1997;128:327–335.

13. Jeske AH, Suchko GD; ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and Division of Science, Journal of the American Dental Association. Lack of a scientific basis for routine discontinuation of oral anticoagulant therapy before dental treatment. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;134:1492–1497 [erratum 2004;135:28].

14. Hirsh J, Dalen JE, Deykin D, Poller L. Oral anticoagulants: Mechanism of action, clinical effectiveness, and optimal therapeutic range. Chest 1992;102(4 suppl):312S–326S.

15. Hirsh J, Fuster V. Guide to anticoagulant therapy. Part 2: Oral anticoagulants. American Heart Association. Circulation 1994;89: 1469–1480.

16. Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal MD, Briët E. Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation 1994;89:635–641.

17. Wahl MJ. Myths of dental surgery in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 2000;131:77–81.

18. Scully C, Wolff A. Oral surgery in patients on anticoagulant therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002;94:57–64.

19. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association: A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138:739–760.

20. Tong DC, Rothwell BR. Antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry: A review and practice recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131:366–374.

21. Brackett SE. Infective endocarditis and mitral valve prolapse— The unsuspected risk. A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982;54:273–276.

Читать дальше