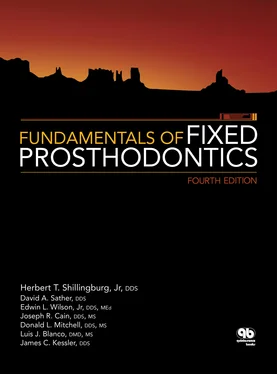

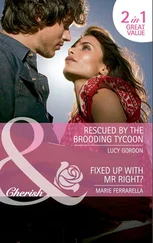

Fig 7-12The combined root surface area of the canine and second molar (A c+ A 2m) is exceeded by that of the teeth being replaced (A 1p+ A 2p+ A 1m). A fixed partial denture would be a poor choice in this situation.

It is possible for fixed partial dentures to replace more than two teeth, the most common examples being anterior fixed partial dentures replacing the four incisors. Canine to second molar fixed partial dentures also are possible (if all other conditions are ideal) in the maxillary arch, but not as often in the mandibular arch. However, any fixed prosthesis replacing more than two teeth should be considered a high risk.

As a clinical guideline, there is some validity in the Ante’s Law concept. Fixed partial dentures with short pontic spans have a better prognosis than do those with excessively long spans. It would be an oversimplification to attribute this merely to overstressing of the periodontal ligament, however. Failures from abnormal stress have been attributed to leverage and torque rather than overload. 1Biomechanical factors and material failure play an important role in the potential for failure of long-span restorations.

There is evidence that teeth with very poor periodontal support can serve successfully as fixed partial denture abutments in carefully selected cases. Teeth with severe bone loss and marked mobility have been used as fixed partial denture and splint abutments. 8Elimination of mobility is not the goal in such cases but rather the stabilization of the teeth in a status quo to prevent an increase of mobility. 9

Abutment teeth in these situations can be maintained free of inflammation in the face of mobility if the patients are well motivated and highly proficient in plaque removal. 10Crowns that anchor rigid prostheses to mobile teeth do require greater retention than do crowns attached to relatively immobile abutments, however. 11Follow-up studies of these patients with so-called terminal dentitions indicate a surprisingly low failure rate—less than 8% of 332 fixed partial dentures exhibited technical failure in a time span that averaged slightly more than 6 years. 12

What is the impact of the success of this type of treatment on fixed partial dentures for the average patient? The successful restoration of mouths with severe periodontal disease does have significance in everyday practice. It emphasizes the extreme importance of carefully evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the remaining dentition on an individual basis.

This should not be a signal for every dentist with a handpiece to start using severely periodontally involved teeth as abutments. One should bear in mind that the successful treatments that have been cited are the work of well-trained and highly skilled clinicians on selected, highly motivated patients.

This type of heroic treatment ( herodontics , if you will) is very demanding technically and expensive as well. Performed by a well-trained, skilled clinician on an informed, motivated patient who dreads tooth loss, understands the patient’s role in the success of the treatment, and accepts the risk (and expense) of failure, it can be a good service. “Sold” by a practitioner without special qualifications to an unmotivated and ill-informed patient, this type of treatment easily could result in a lawsuit.

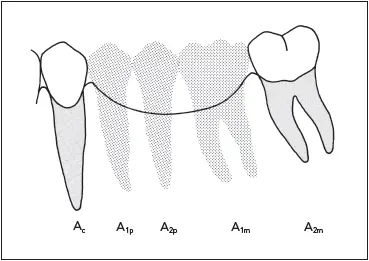

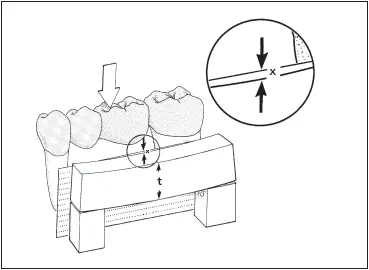

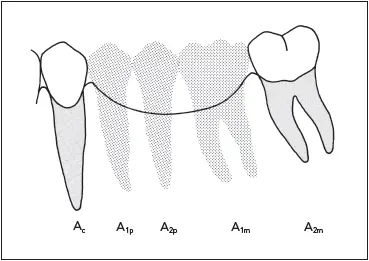

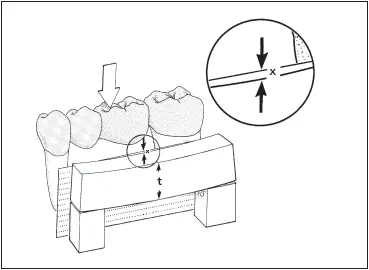

Fig 7-13There is one unit of deflection (x) for a given span length (p).

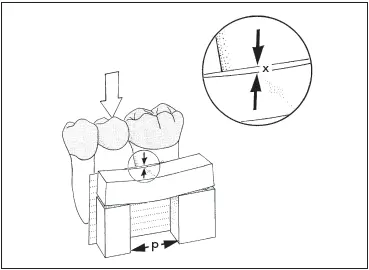

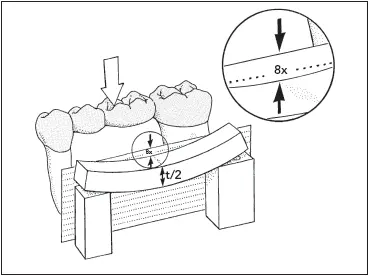

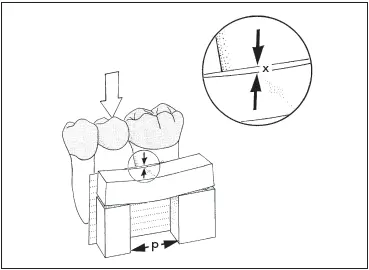

Fig 7-14The deflection will be eight times as great (8x) if the span length is doubled (2p).

Fig 7-15The deflection will be 27 times as great (27x) if the span length is tripled (3p).

Fig 7-16There is one unit of deflection (x) for a pontic with a given thickness (t).

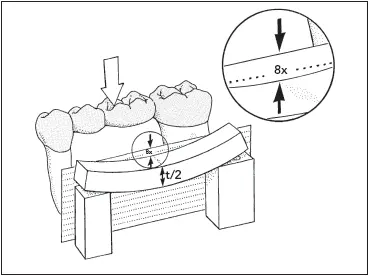

Fig 7-17There will be eight times as much deflection (8x) if the thickness is decreased by one-half (t/2).

Biomechanical Considerations

In addition to the increased load placed on the periodontal ligament by a long-span fixed partial denture, longer spans are less rigid. Bending or deflection varies directly with the cube of the length and inversely with the cube of the occlusogingival thickness of the pontic. Compared with a fixed partial denture having a single-tooth pontic span ( Fig 7-13), a two-tooth pontic span will bend 8 times as much ( Fig 7-14). A three-tooth pontic will bend 27 times as much as a single pontic 13( Fig 7-15).

A pontic with a given occlusogingival dimension ( Fig 7-16) will bend eight times as much if the pontic thickness is halved ( Fig 7-17). Therefore, a long-span fixed partial denture on short mandibular teeth could have disappointing results. Longer pontic spans also have the potential for producing more torquing forces on the fixed partial denture, especially on the weaker abutment. To minimize flexing caused by long and/or thin spans, pontic designs with a greater occlusogingival dimension should be selected. The prosthesis may also be fabricated of an alloy with a higher yield strength, such as nickel-chromium.

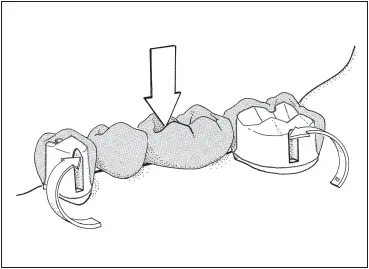

Fig 7-18The walls of facial and lingual grooves counteract mesiodistal torque resulting from force applied to the pontic.

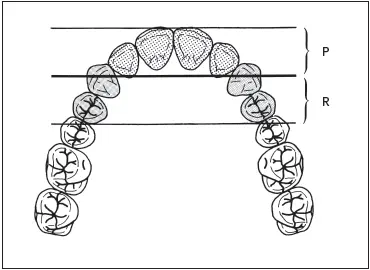

Fig 7-19The retainers on secondary abutments will be placed in tension when the pontics flex, with the primary abutments acting as fulcrums.

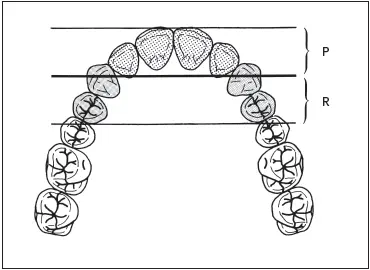

Fig 7-20Secondary retention (R) must extend a distance from the primary interabutment axis equal to the distance that the pontic lever arm (P) extends in the opposite direction.

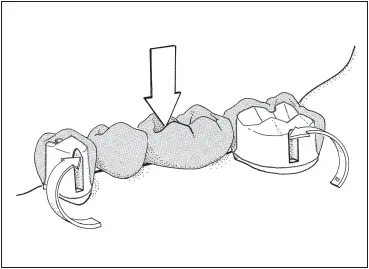

All fixed partial dentures, long or short, flex to some extent. Because of the forces being applied through the pontics to the abutment teeth, the forces on castings serving as retainers for fixed partial dentures are different in magnitude and direction from those applied to single restorations. 14The dislodging forces on a fixed partial denture retainer tend to act in a mesiodistal direction, as opposed to the more common faciolingual direction of forces on a single restoration. Preparations should be modified accordingly to produce greater resistance and structural durability. Multiple grooves, including some on the facial and lingual surfaces, are commonly employed for this purpose ( Fig 7-18).

Читать дальше