Composite resin has been used in the restoration of posterior teeth with mixed results. Sufficient abrasion resistance to prevent occlusal wear has been a problem. Also, unless the resin is carefully applied in small increments, polymerization shrinkage will lead to leakage and ultimately to failure. Its use probably should be restricted to small occlusal and mesio-occlusal restorations on first premolars.

An innovative approach to the prevention of root caries at the margins of restorations that extend from enamel to cementum is the application of a slurry of unfilled resin and sodium fluoride combined with laser energy. 3This approach resulted in a significantly increased resistance to acid and mechanical destruction. In another study, topical fluoride in combination with laser energy provided resistance to enamel caries. 4

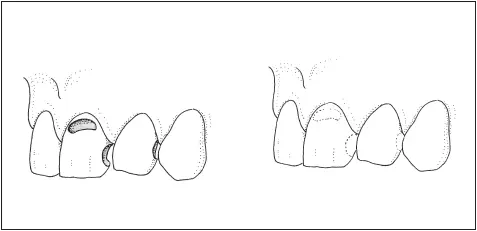

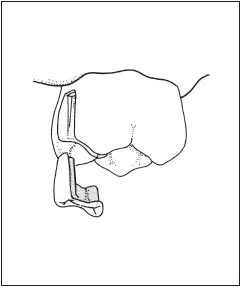

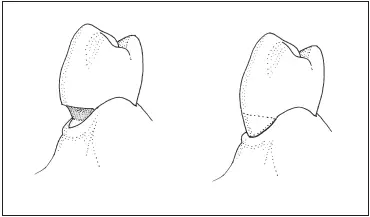

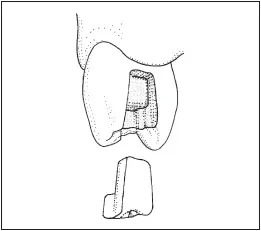

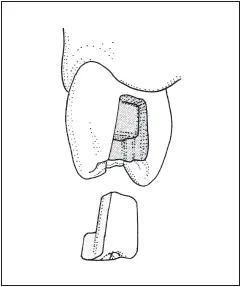

A technique devised to combat the problems of shrinkage and leakage is the fabrication of a composite resin inlay ( Fig 6-7). This can be accomplished in the dental office, using a fast-setting gypsum cast, or in a dental laboratory. The resultant bench-polymerized inlay will have greater hardness, and the thin layer of resin used for affixing it to tooth structure will be less susceptible to significant shrinkage at the margin than a restoration that is bulk cured in situ.

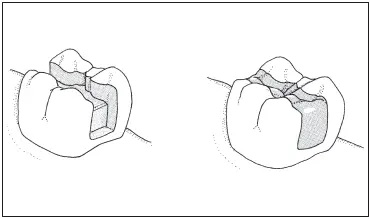

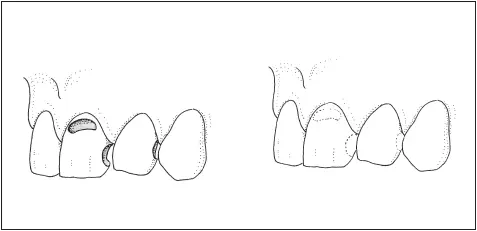

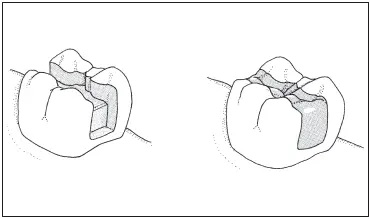

The simple amalgam, without pins or other means of auxiliary retention, for decades has been the standard one- to three-surface restoration for minor- to moderate-sized lesions in esthetically noncritical areas ( Fig 6-8). It has received a good amount of negative attention in the media, and some segments of the profession use this as an excuse to replace otherwise acceptable amalgam restorations with composite resin. The American Dental Association’s Statement on Dental Amalgam states that amalgam is a valuable, viable, and safe choice for dental patients. 5A European Commission’s Scientific Committee also concluded that amalgams are effective and safe. 6They further state that there is no clinical justification for removing satisfactory amalgams except for allergic reactions. Nor is the mere presence of a defective margin alone enough to require replacement. 7Approximately 71 million or more simple amalgam restorations are placed annually. 8They are best used where more than half of the coronal dentin is intact.

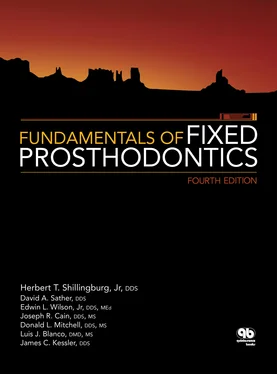

Fig 6-2Glass ionomer can be used to restore gingival abrasion or erosion.

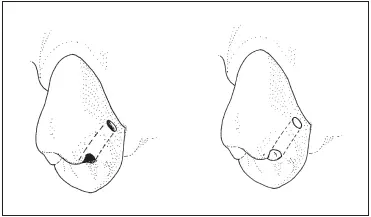

Fig 6-3Tunnel preparation and glass ionomer can be used to restore an incipient lesion on the proximal surface of a posterior tooth.

Fig 6-4Root caries restored with glass ionomer.

Fig 6-5Rampant caries can be brought under control with glass ionomer.

Tooth preparation size for incipient lesions has diminished in recent years as the popularity of the concept of “extension for prevention” has waned. This move toward less destructive preparations has been augmented by the development of smaller instruments and stronger amalgams. Nonetheless, even a minimal preparation for an amalgam restoration significantly weakens the structural integrity of the tooth. 9

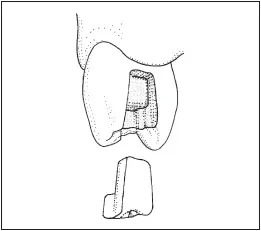

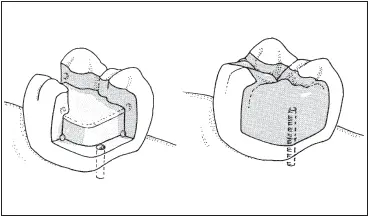

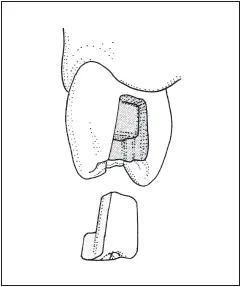

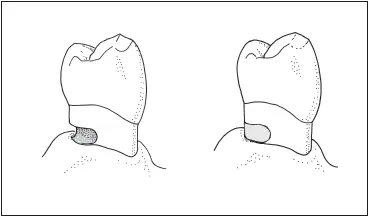

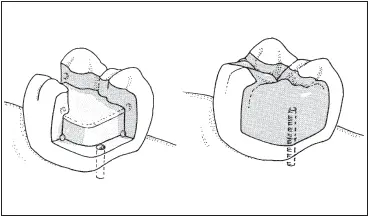

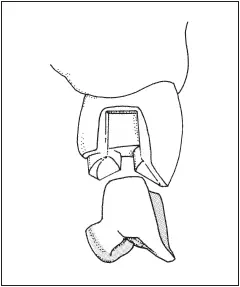

Amalgam augmented by pins or other auxiliary means of retention can be used to restore teeth with moderate to severe lesions in which less than half of the coronal dentin remains ( Fig 6-9). Amalgam used in this manner can be employed as a definitive restoration when a crown is contraindicated because of limited finances or poor oral hygiene. It can be used in the restoration of teeth with missing cusps or endodontically treated premolars and molars—teeth that ordinarily would be restored with mesio-occlusodistal (MOD) onlays or other extracoronal restorations. In such situations, amalgam is used to replace or overlay the cusp to provide the protection of occlusal coverage. Although amalgam produces good strength in the restored tooth, 10ideally a crown should be constructed over the pin-retained amalgam, using it as a core, or foundation restoration.

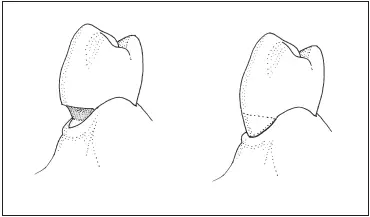

Fig 6-6Composite resin is commonly used to restore Class III and Class V lesions on anterior teeth.

Fig 6-7Indirect inlays of composite resin can be used for proximo-occlusal restorations on posterior teeth.

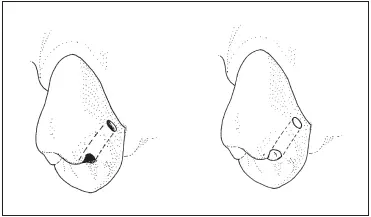

Fig 6-8A simple amalgam restoration placed in an MOD preparation on a molar.

Fig 6-9A complex amalgam restoration replaces a missing cusp on a molar.

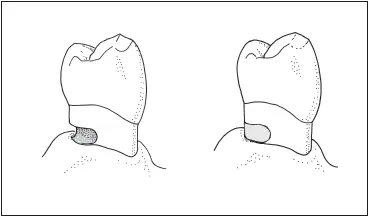

Fig 6-10A metal inlay is used to restore a molar.

Fig 6-11Ceramic inlays can be used to restore posterior teeth.

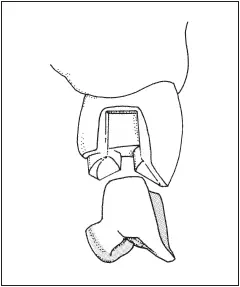

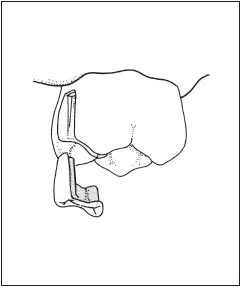

Fig 6-12An MOD onlay for a maxillary premolar.

Teeth with low esthetic requirements and small- to moderatesized lesions can be restored with metal inlay restorations ( Fig 6-10). Although usually made of softer gold alloys, metal inlays also can be fabricated of etchable base metal alloys if a bonding effect is desired. 11,12The preparation isthmus should be narrow to minimize stress in the surrounding tooth structure. Premolars should have one intact marginal ridge to preserve structural integrity and minimize the possibility of coronal fracture.

The additional bulk of tooth structure found in a molar permits the use of this restoration type in an MOD configuration. The indications for this type of restoration are much the same as those for an amalgam because this restoration only replaces lost tooth structure and will not protect remaining tooth structure. Because of the amount of destruction of tooth structure required by this restoration, it is not recommended for incipient lesions.

Читать дальше