Finally, we mention that DFT‐based methods have also been proposed in order to compute Raman and hyper‐Raman spectra for periodic solids [25, 26]. These approaches have been used to calculate the corresponding spectra for the main oxide network‐formers, i.e. SiO 2, B 2O 3, or GeO 2, with a good a very good agreement to experimental data [12, 13, 18].

5 Calculations of NMR Spectra

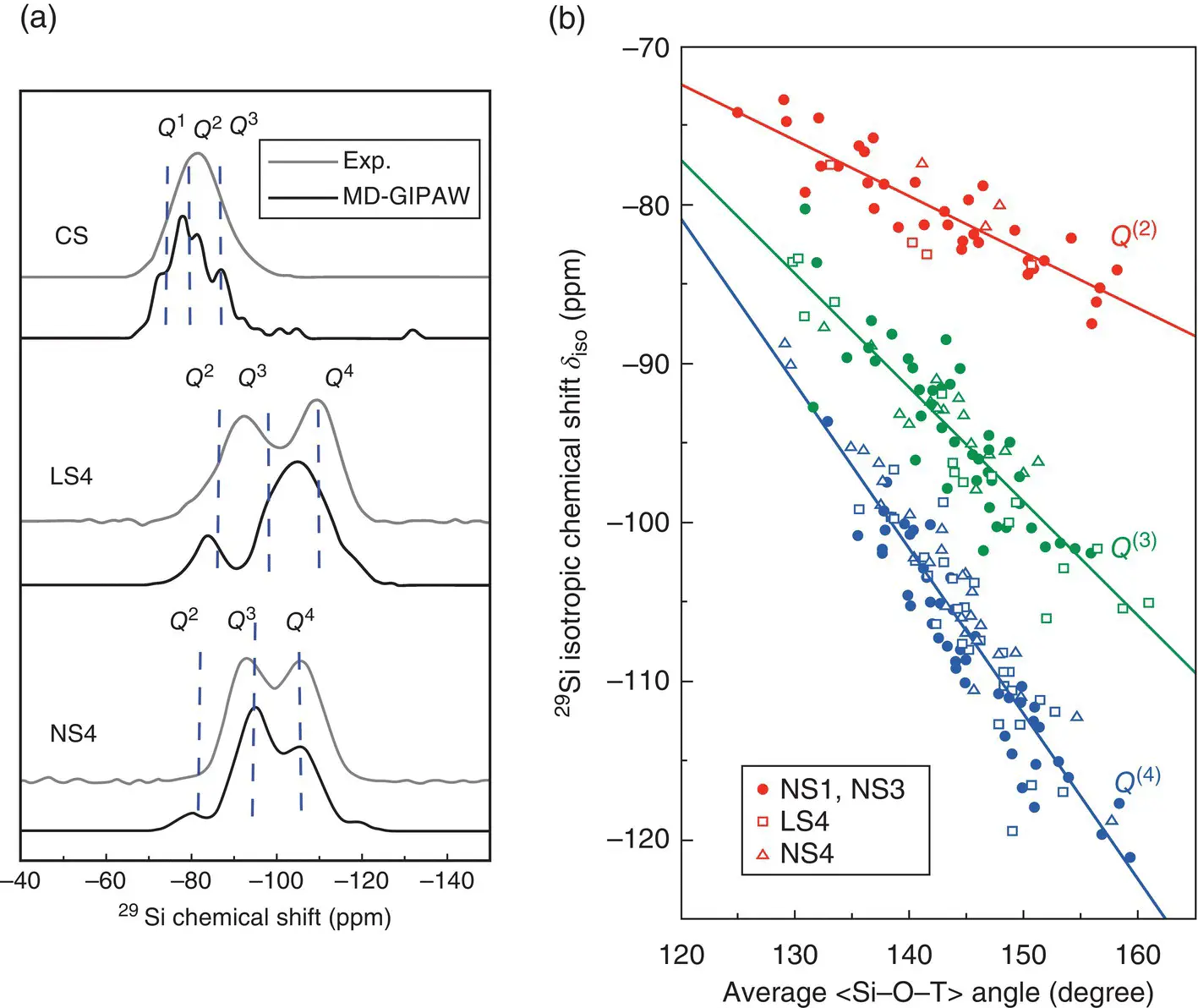

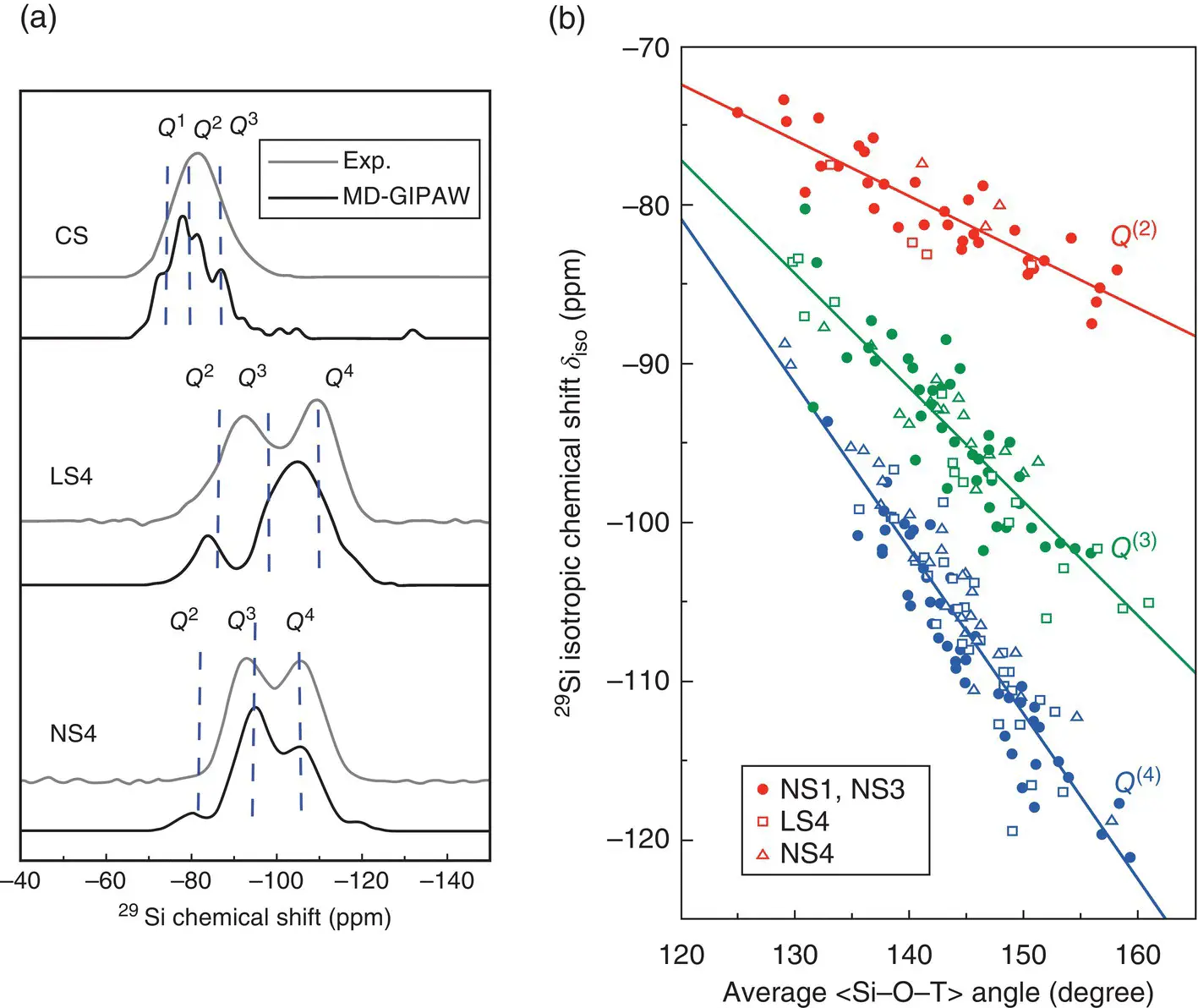

A serious problem faced by NMR experiments on disordered structures is that the observed peaks may overlap so that real‐space interpretations of the spectra are not always straightforward. Theoretical calculations can thus give helpful guidance, but their difficulty is illustrated by the fact that the first NMR schemes have been proposed only 15 years ago. In the glass community, the so‐called GIPAW approach proposed by Pickard and Mauri [27] is certainly the most used one, and implemented in many ab initio packages. However, the theory on how this is done is rather involved, see Ref. [28], and therefore we just illustrate the kind of results obtained with calculations of 29Si Magic Angle Spinning spectra done for binary alkali and alkaline earth silicates ( Figure 6).

Regarding the peak positions, the agreement between the ab initio simulations and the experimental spectra is remarkably good ( Figure 6a). For lithium silicates, slight discrepancies are found for the peak intensities but they are likely due to the modest size and high quenching rates of the simulated samples. In fact, one can handle this problem by determining how the concentrations of the various structural units depend on the cooling rate (or on the temperature of the liquid) and then adjusting them to the actual experimental conditions [6].

Figure 6 Application of ab initio simulations to NMR spectroscopy [29]. (a) [29]Si magic angle spinning spectra of calcium metasilicate (CS), lithium tetrasilicate (LS4), and sodium tetrasilicate (NS4) glasses. (b) Dependence of the [29]Si isotropic chemical shifts on the Si–O–T angle calculated for different Q (n)species in 43 Na 2O–57 SiO 2(NS1), 22.5 Na 2O–77.5 SiO 2(NS3), NS4, and LS4 glasses. Solid lines: linear fits to the data.

Although NMR experiments provide information on the nature of the local structure ( Q [n]‐species, connectivity of the atoms, etc.) it is difficult to extract direct information on the geometry of the local structures, such as bond angles. That ab initio simulations are also useful for this is demonstrated in Figure 6b where we show the chemical shift as a function of Si–O–T angle, where O is a first nearest neighbor of Si atom and T is the second Si atom bonded to that O. The data clearly show: (i) that there is a linear relationship between this angle and the chemical shift, (ii) that this relationship is basically independent of the composition of the glass, and (iii) that its slope depends on the Q (n)‐species of the second Si atom.

Ab initio simulations of glasses have now become standard to determine observables of high practical relevance, but usually inaccessible to simulations with effective potentials. Despite their computational cost, they constitute a most useful tool to gain insights into microscopic properties of glasses, especially when their composition is complex, and even to develop novel types of glasses with exotic compositions. Their accuracy makes them most useful when a multitude of possible local atomic environments coexist either in the bulk or at glass surface or when important structural heterogeneities are found at a microscopic scale. This applies, for instance, to the properties of the charged and neutral defects in amorphous silica, as their presence can strongly affect the performances of electronic and optical devices based on SiO 2[30]. The technologically important chalcogenide glasses ( Chapter 6.5) can only be simulated with force‐fields accounting correctly for homopolar bonds, i.e. ab initio simulations. Because chalcogenides do not contain oxygen, an element that is relatively costly to deal with, they can be investigated with smaller efforts per particle and, thus, quite large systems sizes and accessible timescales [31–33].

Other important topics are the effects of water on bulk and surface properties because the high reactivity of hydrogen induces local modification of the structure which can change the properties of the glass even at very low concentrations. The difficulty is then that fairly large systems must be investigated, which is the reason why relatively few simulations have been done on complex water‐bearing glasses [9, 15]. At present, the main problem faced indeed remains the large computational effort required and hence more efficient methods are being devised to reduce the computing time. Examples are the so‐called “order‐ N ” algorithms, with which the computational cost increases only linearly with the system size [34], or the second‐generation Car–Parrinello approach [35]. Although these advances will make it possible to deal with much larger systems, including, for instance, 10 4oxygen atoms, it is unlikely that they will allow to gain one more order of magnitude in system size. To study problems like the mechanical behavior of glasses on the mesoscale, simulations will thus have to be done with effective potentials. But even in these cases ab initio simulations will be very useful by providing more accurate potential parameters [36–38].

1 1 Frenkel, D. and Smit, B. (1996). Understanding Molecular Simulations: From Algorithms to Applications. San Diego: Academic Press.

2 2 Marx, D. and Hutter, J. (2009). Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics: Basic Theory and Advanced Methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

3 3 Kohn, W. and Sham, L.J. (1965). Self‐consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140: A1133–A1138.

4 4 Car, R. and Parrinello, M. (1985). Unified approach for molecular dynamics and density‐functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55: 2471–2474.

5 5 Jakse, N. and Pasturel, A. (2014). The hydrogen diffusion in liquid aluminum alloys from ab initio molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 141: 094504.

6 6 Pedesseau, L., Ispas, S., and Kob, W. (2015). First‐principles study of a sodium borosilicate glass‐former: I. The liquid state; and II. The glassy state. Phys. Rev. B 91: 134201, ibid. 134202.

7 7 Sarnthein, J., Pasquarello, A., and Car, R. (1995). Model of vitreous SiO2 generated by an ab initio molecular‐dynamics quench from the melt. Phys. Rev. B 52: 12690–12695.

8 8 Ispas, S., Benoit, M., Jund, P., and Jullien, R. (2001). Structural and electronic properties of the sodium tetrasilicate glass Na2Si2O9 from classical and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. B 64: 214206.

9 9 Pöhlmann, M., Benoit, M., and Kob, W. (2004). First‐principles molecular‐dynamics simulations of a hydrous silica melt: structural properties and hydrogen diffusion mechanism. Phys. Rev. B 70: 184209.

10 10 Du, J. and Corrales, L.R. (2006). Structure, dynamics, and electronic properties of lithium disilicate melt and glass. J. Chem. Phys. 125: 114702.

11 11 Spiekermann, G., Steele‐MacInnis, M., Kowalski, P.M. et al. (2013). Vibrational properties of silica species in MgO–SiO2 glasses obtained from ab initio molecular dynamics. Chem. Geol. 346: 22–33.

12 12 Giacomazzi, L., Umari, P., and Pasquarello, A. (2005). Medium‐range structural properties of vitreous germania obtained through first‐principles analysis of vibrational spectra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95: 075505.

Читать дальше