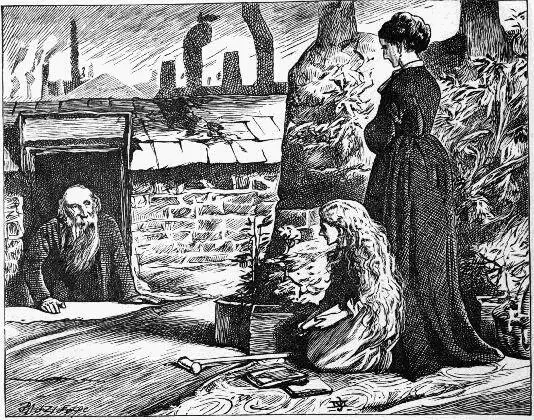

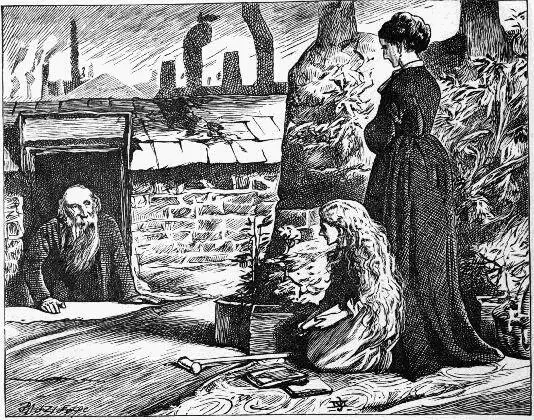

Thus, Fascination Fledgeby went his way, exulting in the artful cleverness with which he had turned his thumb down on a Jew, and the old man went his different way up-stairs. As he mounted, the call or song began to sound in his ears again, and, looking above, he saw the face of the little creature looking down out of a Glory of her long bright radiant hair, and musically repeating to him, like a vision:

‘Come up and be dead! Come up and be dead!’

Chapter 6.

A Riddle Without an Answer

Table of Contents

Again Mr Mortimer Lightwood and Mr Eugene Wrayburn sat together in the Temple. This evening, however, they were not together in the place of business of the eminent solicitor, but in another dismal set of chambers facing it on the same second-floor; on whose dungeon-like black outer-door appeared the legend:

PRIVATE MR EUGENE WRAYBURN MR MORTIMER LIGHTWOOD

(Mr Lightwood’s Offices opposite.)

Appearances indicated that this establishment was a very recent institution. The white letters of the inscription were extremely white and extremely strong to the sense of smell, the complexion of the tables and chairs was (like Lady Tippins’s) a little too blooming to be believed in, and the carpets and floorcloth seemed to rush at the beholder’s face in the unusual prominency of their patterns. But the Temple, accustomed to tone down both the still life and the human life that has much to do with it, would soon get the better of all that.

‘Well!’ said Eugene, on one side of the fire, ‘I feel tolerably comfortable. I hope the upholsterer may do the same.’

‘Why shouldn’t he?’ asked Lightwood, from the other side of the fire.

‘To be sure,’ pursued Eugene, reflecting, ‘he is not in the secret of our pecuniary affairs, so perhaps he may be in an easy frame of mind.’

‘We shall pay him,’ said Mortimer.

‘Shall we, really?’ returned Eugene, indolently surprised. ‘You don’t say so!’

‘I mean to pay him, Eugene, for my part,’ said Mortimer, in a slightly injured tone.

‘Ah! I mean to pay him too,’ retorted Eugene. ‘But then I mean so much that I—that I don’t mean.’

‘Don’t mean?’

‘So much that I only mean and shall always only mean and nothing more, my dear Mortimer. It’s the same thing.’

His friend, lying back in his easy chair, watched him lying back in his easy chair, as he stretched out his legs on the hearth-rug, and said, with the amused look that Eugene Wrayburn could always awaken in him without seeming to try or care:

‘Anyhow, your vagaries have increased the bill.’

‘Calls the domestic virtues vagaries!’ exclaimed Eugene, raising his eyes to the ceiling.

‘This very complete little kitchen of ours,’ said Mortimer, ‘in which nothing will ever be cooked—’

‘My dear, dear Mortimer,’ returned his friend, lazily lifting his head a little to look at him, ‘how often have I pointed out to you that its moral influence is the important thing?’

‘Its moral influence on this fellow!’ exclaimed Lightwood, laughing.

‘Do me the favour,’ said Eugene, getting out of his chair with much gravity, ‘to come and inspect that feature of our establishment which you rashly disparage.’ With that, taking up a candle, he conducted his chum into the fourth room of the set of chambers—a little narrow room—which was very completely and neatly fitted as a kitchen. ‘See!’ said Eugene, ‘miniature flour-barrel, rolling-pin, spice-box, shelf of brown jars, chopping-board, coffee-mill, dresser elegantly furnished with crockery, saucepans and pans, roasting jack, a charming kettle, an armoury of dish-covers. The moral influence of these objects, in forming the domestic virtues, may have an immense influence upon me; not upon you, for you are a hopeless case, but upon me. In fact, I have an idea that I feel the domestic virtues already forming. Do me the favour to step into my bedroom. Secretaire, you see, and abstruse set of solid mahogany pigeon-holes, one for every letter of the alphabet. To what use do I devote them? I receive a bill—say from Jones. I docket it neatly at the secretaire, Jones , and I put it into pigeonhole J. It’s the next thing to a receipt and is quite as satisfactory to me . And I very much wish, Mortimer,’ sitting on his bed, with the air of a philosopher lecturing a disciple, ‘that my example might induce you to cultivate habits of punctuality and method; and, by means of the moral influences with which I have surrounded you, to encourage the formation of the domestic virtues.’

Mortimer laughed again, with his usual commentaries of ‘How can you be so ridiculous, Eugene!’ and ‘What an absurd fellow you are!’ but when his laugh was out, there was something serious, if not anxious, in his face. Despite that pernicious assumption of lassitude and indifference, which had become his second nature, he was strongly attached to his friend. He had founded himself upon Eugene when they were yet boys at school; and at this hour imitated him no less, admired him no less, loved him no less, than in those departed days.

‘Eugene,’ said he, ‘if I could find you in earnest for a minute, I would try to say an earnest word to you.’

‘An earnest word?’ repeated Eugene. ‘The moral influences are beginning to work. Say on.’

‘Well, I will,’ returned the other, ‘though you are not earnest yet.’

‘In this desire for earnestness,’ murmured Eugene, with the air of one who was meditating deeply, ‘I trace the happy influences of the little flour-barrel and the coffee-mill. Gratifying.’

‘Eugene,’ resumed Mortimer, disregarding the light interruption, and laying a hand upon Eugene’s shoulder, as he, Mortimer, stood before him seated on his bed, ‘you are withholding something from me.’

Eugene looked at him, but said nothing.

‘All this past summer, you have been withholding something from me. Before we entered on our boating vacation, you were as bent upon it as I have seen you upon anything since we first rowed together. But you cared very little for it when it came, often found it a tie and a drag upon you, and were constantly away. Now it was well enough half-a-dozen times, a dozen times, twenty times, to say to me in your own odd manner, which I know so well and like so much, that your disappearances were precautions against our boring one another; but of course after a short while I began to know that they covered something. I don’t ask what it is, as you have not told me; but the fact is so. Say, is it not?’

‘I give you my word of honour, Mortimer,’ returned Eugene, after a serious pause of a few moments, ‘that I don’t know.’

‘Don’t know, Eugene?’

‘Upon my soul, don’t know. I know less about myself than about most people in the world, and I don’t know.’

‘You have some design in your mind?’

‘Have I? I don’t think I have.’

‘At any rate, you have some subject of interest there which used not to be there?’

‘I really can’t say,’ replied Eugene, shaking his head blankly, after pausing again to reconsider. ‘At times I have thought yes; at other times I have thought no. Now, I have been inclined to pursue such a subject; now I have felt that it was absurd, and that it tired and embarrassed me. Absolutely, I can’t say. Frankly and faithfully, I would if I could.’

So replying, he clapped a hand, in his turn, on his friend’s shoulder, as he rose from his seat upon the bed, and said:

‘You must take your friend as he is. You know what I am, my dear Mortimer. You know how dreadfully susceptible I am to boredom. You know that when I became enough of a man to find myself an embodied conundrum, I bored myself to the last degree by trying to find out what I meant. You know that at length I gave it up, and declined to guess any more. Then how can I possibly give you the answer that I have not discovered? The old nursery form runs, “Riddle-me-riddle-me-ree, p’raps you can’t tell me what this may be?” My reply runs, “No. Upon my life, I can’t.”’

Читать дальше