Generally speaking, beekeepers (whether hobbyist or commercial) harvest their honey at the conclusion of a substantial nectar flow and when the hive is filled with cured and capped honey (see Figure 2-4). Conditions and circumstances and timing vary greatly across the country.

Photo by C. Marina Marchese

FIGURE 2-4:This frame is ready to harvest, as the bees have filled nearly every cell with cured honey and sealed each cell with a white capping of beeswax.

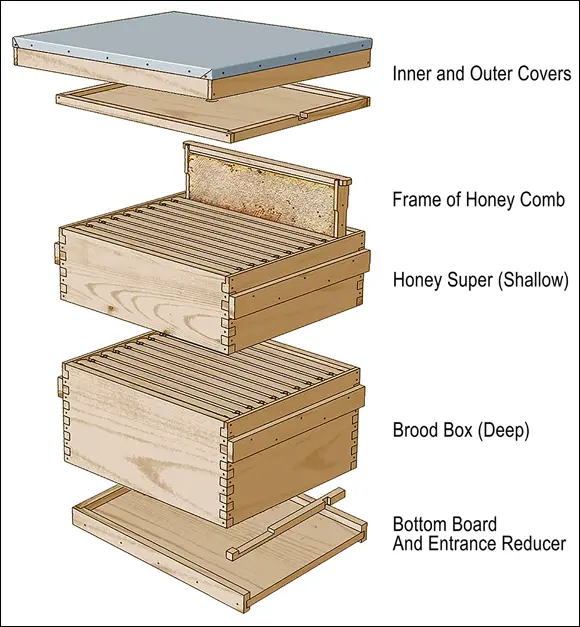

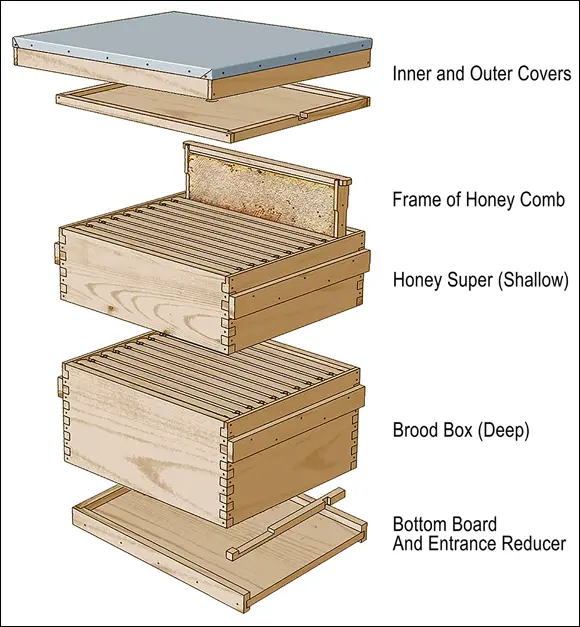

The honey that is taken from the beehive is considered surplus honey . This term refers to the honey that’s beyond what the bees need for their own consumption. This extra amount of honey is what the beekeeper can safely harvest from the hive without creating trouble for the colony (See Figure 2-5 for the components of a typical beehive).The bees may not have known at the time, but they made the surplus just for you and me! On average, a hive produces about 65 pounds of surplus honey each season. There is more in a really good season. Like farming, the yield all depends on the robustness of the bees, weather, rainfall, available forage, and other variable circumstances. Most are beyond the beekeeper’s control.

The honey that is taken from the beehive is considered surplus honey . This term refers to the honey that’s beyond what the bees need for their own consumption. This extra amount of honey is what the beekeeper can safely harvest from the hive without creating trouble for the colony (See Figure 2-5 for the components of a typical beehive).The bees may not have known at the time, but they made the surplus just for you and me! On average, a hive produces about 65 pounds of surplus honey each season. There is more in a really good season. Like farming, the yield all depends on the robustness of the bees, weather, rainfall, available forage, and other variable circumstances. Most are beyond the beekeeper’s control.

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 2-5:This illustration shows the anatomy of a typical beehive. The surplus honey that is harvested comes from the top boxes, called “honey supers.”

A substance is hygroscopic if it absorbs moisture from the air. Honey is one of those hygroscopic substances. On the positive side, this is why baked goods made with honey stay moist and fresh. It’s also why honey is used in cosmetics as a moisturizer. On the negative side, being hygroscopic means you must keep your honey containers tightly sealed; otherwise, your honey will absorb moisture from the air, become diluted, and eventually ferment. That’s why the bees seal the honeycomb cells with an airtight lid of beeswax.

Driving the bees out of the honey supers

Before beekeepers can extract the honey and bottle it, they must remove the bees from the frame’s honeycomb. Beekeepers certainly don’t need to bring thousands of bees into their extraction and bottling facility!

Removing bees from honeycomb can be accomplished in many different ways. But for commercial beekeepers (those with over 300 hives) and even for hobbyists with ten or more hives, the fastest and most practical way is to use a fume board . It looks like a hive cover, but it has an absorbent flannel inner lining. A liquid bee repellent is applied to the flannel lining, and the fume board is placed on top of the honey supers on a warm day. After just a few minutes, the bees are repelled out of the honey supers and down into the brood chamber. Instant success! The honey supers can then be safely removed and taken to the designated workspace for removing the honey from the comb.

Removing the honey from the comb

After collecting the frames of capped honeycomb (sans bees), beekeepers (large and small) follow the same process (illustrated in Figure 2-6) to get the honey out of the comb and bottle it. Only the scale of operations and size of equipment change. Here’s how the process works for both:

1 After removing the bees and bringing the honey supers into a workspace, the beekeeper removes each frame of capped honey from the supers.

2 A handheld knife or uncapping machine is used to slice off the wax cappings and expose the cells of ripened honey.This process is called uncappin g .

3 An uncapping fork (or similar device) is used to get any cells missed by the knife or uncapping machine.

4 Once the frames are uncapped, they are placed in a centrifugal extractor.As the frames spin, the honey is forced out of the cells and dribbles down the walls of the extractor into a holding area.

5 The honey is drained from the extractor, filtered, put into airtight containers, and labeled.

Photography by Howland Blackiston (top) and www.cooknbeals.com (bottom)

FIGURE 2-6:These photos show the process for both a hobbyist beekeeper and a commercial operation. The steps are similar; only the scale of operations and size of equipment varies.

Chapter 3

Appreciating the Different Styles of Honey

IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting to know the four main styles of honey

Getting to know the four main styles of honey

Understanding crystallization

Understanding crystallization

Making your own creamed honey

Making your own creamed honey

Honey comes in thousands of different varieties, really as many as there are different flowers. In Chapter 7I profile 50 of the most popular varieties of honey. When you purchase honey, regardless of the variety, honey can be presented as one of several different styles . In this chapter we’re talking about the different styles of honey. And there are only four style variations: comb honey, extracted honey, chunk honey and whipped honey. They are all worth a try and enjoyed in different ways.

In time, nearly all honeys form granulated crystals. There is nothing wrong with honey that has crystallized. It’s perfectly okay to eat it in this form. However, if you want to get it back to the liquid state, crystallized honey can be easily liquefied by placing the jar in warm (not hot) water and stirred.

In time, nearly all honeys form granulated crystals. There is nothing wrong with honey that has crystallized. It’s perfectly okay to eat it in this form. However, if you want to get it back to the liquid state, crystallized honey can be easily liquefied by placing the jar in warm (not hot) water and stirred.

Don’t ever be tempted to heat plastic honey jars. The plastic can leech into the honey causing it to smell and taste like, you guessed it, like plastic. And besides, the chances are pretty good that you’ll wind up with a deformed plastic bottle. For this reason, we recommend you always purchase your honey in glass containers.

Don’t ever be tempted to heat plastic honey jars. The plastic can leech into the honey causing it to smell and taste like, you guessed it, like plastic. And besides, the chances are pretty good that you’ll wind up with a deformed plastic bottle. For this reason, we recommend you always purchase your honey in glass containers.

Walkin’ Talkin’ Honeycomb

Comb honey (see Figure 3-1) is the jewel of the beehive — and carries a high retail price as a result. It’s honey just as the bees made it, still in the comb. In many countries, honey in the comb is considered the only authentic honey untouched by humans while retaining all its pollen, propolis, and the natural health benefits associated with raw honey (never extracted, strained or touched by humans). When you uncap those tiny airtight beeswax cells, the honey inside is exposed to the air for the very first time since the bees stored it.

Читать дальше

The honey that is taken from the beehive is considered surplus honey . This term refers to the honey that’s beyond what the bees need for their own consumption. This extra amount of honey is what the beekeeper can safely harvest from the hive without creating trouble for the colony (See Figure 2-5 for the components of a typical beehive).The bees may not have known at the time, but they made the surplus just for you and me! On average, a hive produces about 65 pounds of surplus honey each season. There is more in a really good season. Like farming, the yield all depends on the robustness of the bees, weather, rainfall, available forage, and other variable circumstances. Most are beyond the beekeeper’s control.

The honey that is taken from the beehive is considered surplus honey . This term refers to the honey that’s beyond what the bees need for their own consumption. This extra amount of honey is what the beekeeper can safely harvest from the hive without creating trouble for the colony (See Figure 2-5 for the components of a typical beehive).The bees may not have known at the time, but they made the surplus just for you and me! On average, a hive produces about 65 pounds of surplus honey each season. There is more in a really good season. Like farming, the yield all depends on the robustness of the bees, weather, rainfall, available forage, and other variable circumstances. Most are beyond the beekeeper’s control.

Getting to know the four main styles of honey

Getting to know the four main styles of honey In time, nearly all honeys form granulated crystals. There is nothing wrong with honey that has crystallized. It’s perfectly okay to eat it in this form. However, if you want to get it back to the liquid state, crystallized honey can be easily liquefied by placing the jar in warm (not hot) water and stirred.

In time, nearly all honeys form granulated crystals. There is nothing wrong with honey that has crystallized. It’s perfectly okay to eat it in this form. However, if you want to get it back to the liquid state, crystallized honey can be easily liquefied by placing the jar in warm (not hot) water and stirred. Don’t ever be tempted to heat plastic honey jars. The plastic can leech into the honey causing it to smell and taste like, you guessed it, like plastic. And besides, the chances are pretty good that you’ll wind up with a deformed plastic bottle. For this reason, we recommend you always purchase your honey in glass containers.

Don’t ever be tempted to heat plastic honey jars. The plastic can leech into the honey causing it to smell and taste like, you guessed it, like plastic. And besides, the chances are pretty good that you’ll wind up with a deformed plastic bottle. For this reason, we recommend you always purchase your honey in glass containers.