The ancient Romans valued honey, and like the Egyptians, used it to pay taxes. Because honey was rare and precious, it was a food only enjoyed by Romans who could afford it. Honey’s culinary use is well documented in a cookbook by a Roman gourmand named Marcus Gavius Apicius. Thought to be written in the first century AD, his book is commonly referred to as “Apicius.” Be sure to have a look at Chapters 15and 16. Each contains an ancient Roman honey-inspired recipe. Hail Caesar!

Songs about honey (and honey bees) are plentiful. No big surprise, since “honey” has evolved into a term of endearment. In Chapter 19, I include a playlist of honey music you can groove to.

Hoodoo is an old spiritual practice — a mixture of African, Native American, and European Christian folklore. Honey plays an important role in some of the magic spells practiced by its followers. For example, here’s one you can try at home. To sweeten up someone’s feelings toward you, pour honey into a saucer and place it on a piece of paper containing the intended person’s name. Place a candle (beeswax, I assume) in the saucer and let it burn until it goes out on its own. Now, just sit back and wait for the phone to ring.

And who can forget the adorable Winnie the Pooh? That loveable bear had an unwavering love for “hunny.” And as Pooh said, “A day without a friend is like a pot without a single drop of honey left inside.” Thank you, A. A. Milne.

Honey Bees Come to America

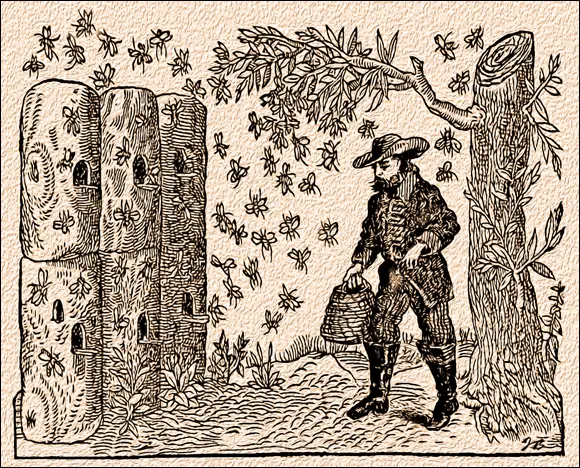

The European honey bee that we see on the flowers in our gardens is not native to the Americas. The first hives of honey bees came to Virginia aboard a ship in the spring of 1622 (see Figure 1-6). The early European settlers made good use of the honey and the beeswax that the colonies produced. The colonists also brought with them specific plants for the bees to pollinate. More bee colonies arrived on ships in the following years, and swarms from these original hives proliferated as feral bee colonies were established. But it was not until 1853 that the honey bees made their way to the west coast. Today, the estimated number of “managed” beehives in America is approaching 3 million colonies. (See Chapter 6for the top ten honey-producing states in America.)

Illustration by Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 1-6:The honey bee, so familiar in the Americas today, is not native to this part of the world. The first honey bees were brought to Virginia by the early colonists in 1622.

Honey Today: Celebrity Status

Have you noticed? Honey seems to be everywhere these days. Honey varietals occupy more and more space on grocery shelves. It’s the “all-natural” sweetener found in breakfast cereals and beverages; it’s the miraculous ingredient in cosmetics; it’s a featured “healing” product in health-food stores; it has found its way into the kitchens of the most elegant and refined restaurants. It’s a star on many menus, spotlighted for its healthy and sophisticated taste profiles, distinct varieties, and pairing opportunities. There’s no doubt that honey has gained the same “celebrity” status as fine cheeses, olive oils, and rare and expensive balsamic vinegars. Foodies and chefs alike realize that like great wine, honey can also be enjoyed by pairing it with fine foods and by bringing distinct flavors to many recipes.

This entire book is a celebration of honey’s newfound celebrity status. In Chapter 7you can find out about 50 different honey varietals and the foods they go well with. And in Chapters 9and 10you can discover how to taste, evaluate, and appreciate the nuances of different honey varietals. In Chapters 14– 17you will find fabulous recipes for making delicious wine from honey, baking with honey, cooking with honey, and even whipping up honey-based beverages and cocktails. To top it all off, Chapter 18gives guidance in how to pair different honeys with food, and Chapter 19shares ideas for planning and hosting a party where Honey is your featured guest.

Savor and enjoy!

Chapter 2

Looking at How Honey Is Made and Harvested

IN THIS CHAPTER

Foraging for sustenance

Foraging for sustenance

Taking a look at the composition of honey

Taking a look at the composition of honey

Seeing how honey is harvested

Seeing how honey is harvested

Honey bees are the only insects that produce a food that consumers eat. And we eat a lot of it. Here in the United States, the annual per capita consumption is around 1.7 pounds per person (eaten on its own, in cooking and baking, and as a sweetening ingredient in other food products).

Considering the U.S. population is around 328 million people, that’s a whole lot of honey. But the bees don’t do all that work just to feed us. It’s their own sustenance.

In this chapter, you discover why and how bees make honey, the good stuff that honey contains, and how it’s harvested. Plus, you find some interesting betcha-didn’t-know info about the bees themselves.

Gathering Their Groceries

There are two raw ingredients that bees collect to convert into the foods they eat for nourishment: pollen and nectar.

The actual pollen-based food bees eat is called beebread . It’s processed from the pollen that the field bees collect from flowering plants. This is the bees’ source of protein. According to the USDA, pollen has between 2.5 percent to 61 percent protein content (depending upon its source). Visiting a flower, the foraging bee uses the pollen baskets on her rear legs to store and transport the pollen home (see Figure 2-1). Although pollen is not used by the bees to make honey, grains of pollen are found in all honeys and become part of the nutritional goodness of honey.

Photo by Stephen Ausmus, USDA Agricultural Research Service

FIGURE 2-1:Photo of a worker field bee collecting pollen. Note the pollen baskets on her rear legs packed with pollen for the return trip to the hive.

The field bees also forage flowering plants to collect nectar. This is what the bees use to make honey. Once they have chosen an attractive, sweet-smelling flower, they suck up nectar with their long, straw-like tongue (see Figure 2-2). Bees visit many flowers (about 40 per minute), eventually carrying the collected nectar back to their colony in a distension of the esophagus called a honey sac (also sometimes called the honey stomach ). They can carry more than their own weight in nectar. Once back in the hive, the house worker bees take over (see the “Busy as a bee” sidebar).

USGS Native Bee Lab

FIGURE 2-2:Note the long tongue on this honey bee. It unrolls like a noisemaker on New Year’s Eve.

There’s a reason the saying “busy as a bee” exists. In their relatively short life during the summer (six weeks), the all-female worker bees pack in a lot of job responsibilities. Worker honey bees spend the first few weeks of their lives carrying out very specific tasks within the hive. For this reason, they are referred to as house bees . The jobs they do are dependent on their age:

Читать дальше

Foraging for sustenance

Foraging for sustenance