Current production quality, combined with low prices, should make it possible to allow experimentation in the near future, and perhaps, even a lifting of the current ban on the use of lactic acid in winemaking.

The fact that a wine has an acid–base buffer capacity also makes deacidification possible. The additives authorized for deacidifying wines are potassium bicarbonate (KHCO 3) and calcium carbonate (CaCO 3). They both form insoluble salts with tartaric acid, and the corresponding acidity is eliminated in the form of carbonic acid (H 2CO 3) that breaks down into CO 2and H 2O. A comparison of the molecular weights of these two salts and the stoichiometry of the neutralization reactions lead to the conclusion that, in general, one gram of KHCO 3(MW = 100) added to one liter of wine produces a drop in acidity of 0.49 g/l, expressed in grams of H 2SO 4(MW = 98). Adding one gram of CaCO 3(MW = 100) to a liter of wine produces a decrease in acidity equal to its own weight (exactly 0.98 g/l), expressed in grams of sulfuric acid.

In fact, this is a rather simplistic explanation, as it disregards the side effects of the precipitation of insoluble potassium bitartrate salts and especially calcium tartrate, on total acidity as well as pH. These side effects of deacidification are only fully expressed in wines with a pH of 3.6 or lower after cold stabilization to remove tartrates. It is obvious from the pH expression ( Equation (1.2)) that, paradoxically, after removal of the precipitated tartrates, deacidification using CaCO 3and, more particularly, KHCO 3is found to reduce the [salt]/[acid] ratio, i.e. increased true acidity. Fortunately, the increase in pH observed during neutralization is not totally reversed.

According to the results described by Usseglio‐Tomasset (1989), a comparison of the deacidifying capacities of potassium bicarbonate and calcium carbonate shows that, in wine, the maximum deacidifying capacity of the calcium salt is only 85% of that of the potassium salt. Consequently, to bring a wine to the desired pH, a larger quantity of CaCO 3than KHCO 3must be used as compared with the theoretical value. On the other hand, CaCO 3has a more immediate effect on pH, as the crystallization of CaT is more complete than that of KHT, a more soluble salt.

In practice, CaCO 3causes an instantaneous reduction in total acidity that is absolutely foreseeable (1 g/l expressed as H 2SO 4for 1 g/l CaCO 3added). Unfortunately, it creates an increase in calcium, which may induce difficult‐to‐control precipitations later on. Nevertheless, its use must be favored in winemaking. In contrast, KHCO 3leads to a low, progressive acidity drop, which continues throughout the precipitation of KHT. It is not easy to determine the necessary dose for a given deacidification. In general, a lower dose than the theoretical one is used. However, the absence of calcium enables easier stabilization after treatment. Its use is recommended for minor deacidification of finished wine (for example, addition of 40–45 g/hl for an acidity drop, expressed as H 2SO 4, of 0.3 g/l).

In any case, such an operation requires a certain degree of prudence. It is actually controlled by the legislation of various countries. Too significant a correction for acidity should not be sought, considering the fact that deacidification with these methods only affects tartaric acid. This accentuates the tartrate/malate imbalance in the total acidity in wines that have not completed malolactic fermentation, as the potassium and calcium salts of malic acid are soluble.

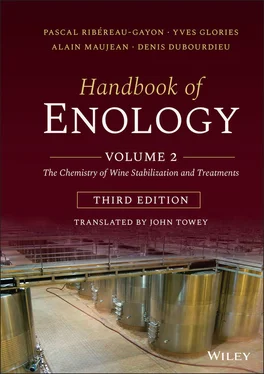

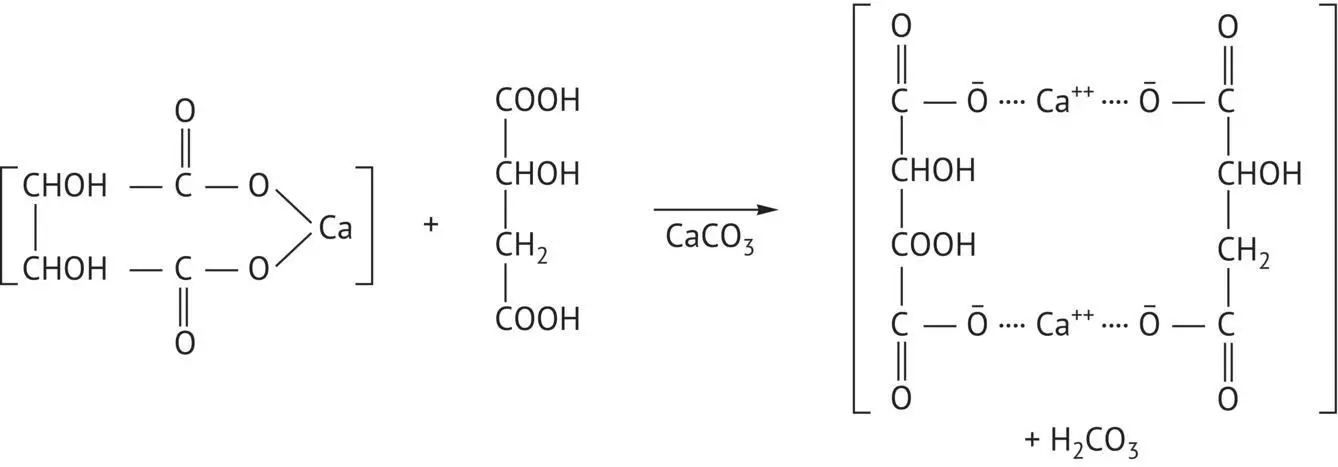

There is a way of deacidifying these wines while maintaining the ratio of tartaric acid to malic acid. The idea is to take advantage of the insolubility of calcium tartromalate, discovered by Ordonneau (1891). Wurdig and Muller (1980) used malic acid's property of displacing tartaric acid from its calcium salt, at pH above 4.5 (higher than the p K a2of tartaric acid), in a reaction ( Figure 1.9) producing calcium tartromalate.

FIGURE 1.9 Formation of insoluble calcium tartromalate when calcium tartrate reacts with malic acid in the presence of calcium carbonate.

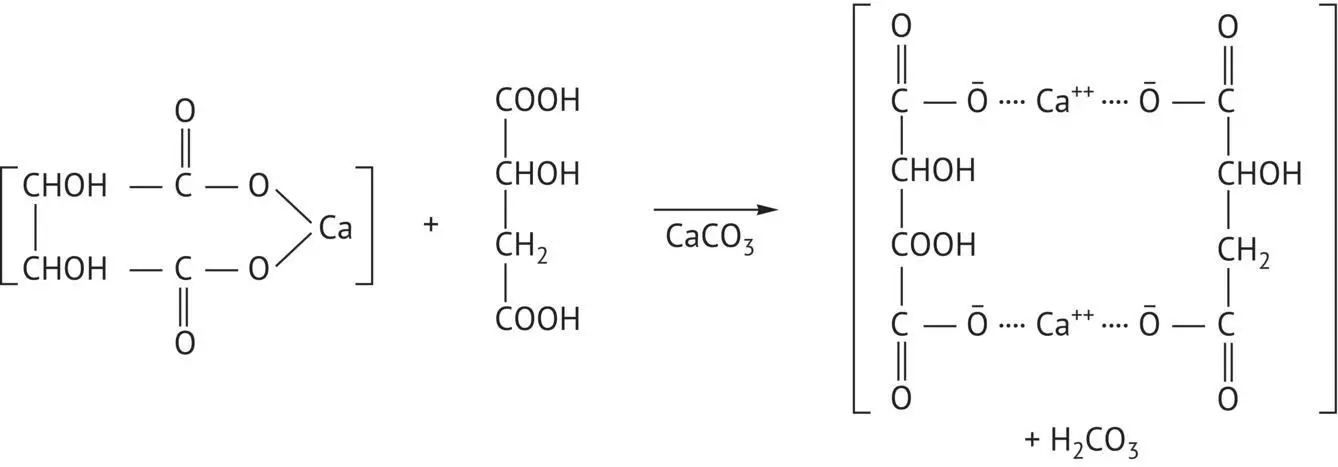

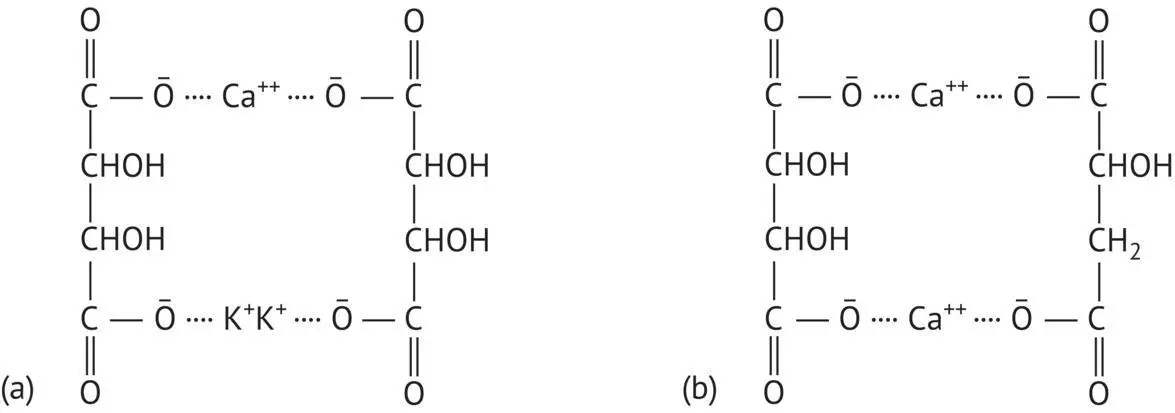

The technology used to implement this deacidification, known as the DICALCIC process (Vialatte and Thomas, 1982), consists in taking volume V , calculated from Equation (1.5)below, of wine to be treated and adding to it the quantity of CaCO 3necessary to obtain the desired deacidification of the total volume ( V T):

(1.5)

In Equation (1.5), A iand A frepresent initial and final acidity, respectively, expressed in grams of H 2SO 4per liter of the total volume V T. The volume V of wine to be deacidified by crystallization and elimination of the calcium tartromalate must be poured over an alkaline mixture consisting, for example, of calcium carbonate (1 part) and calcium tartrate (2 parts). Its residual acidity will then be very close to 1 g/l as H 2SO 4.

It is important that the wine should neutralize the CaCO 3/CaT mixture and not the reverse, as the formation of the stable, crystallizable, double tartromalate salt is only possible above pH 4.5. Below this pH, precipitation of endogenous calcium tartrate occurs, promoted by homogeneous induced nucleation with the added calcium tartrate, as well as precipitation of potassium bitartrate by heterogeneous induced nucleation (Robillard et al ., 1994).

The addition of calcium tartrate is necessary not only to ensure that the tartaric acid content in the wine does not restrict the desired elimination of malic acid by crystallization of the double tartromalate salt but also to maintain a balance between the remaining malic and tartaric acid.

1.5 Tartrate Precipitation Mechanism and Predicting Its Effects

At the pH of wine, and in view of the inevitable presence of K +and Ca 2+cations, tartaric acid is mainly found in the following five salt forms, according to its two dissociation equilibria:

Potassium bitartrate (or KHT) with the formula KHC4H4O6;

Neutral potassium tartrate (K2T);

Neutral calcium tartrate (CaT) with the formula CaC4–H4O6·4H2O;

Potassium calcium double tartrate;

Calcium tartromalate mixed salt.

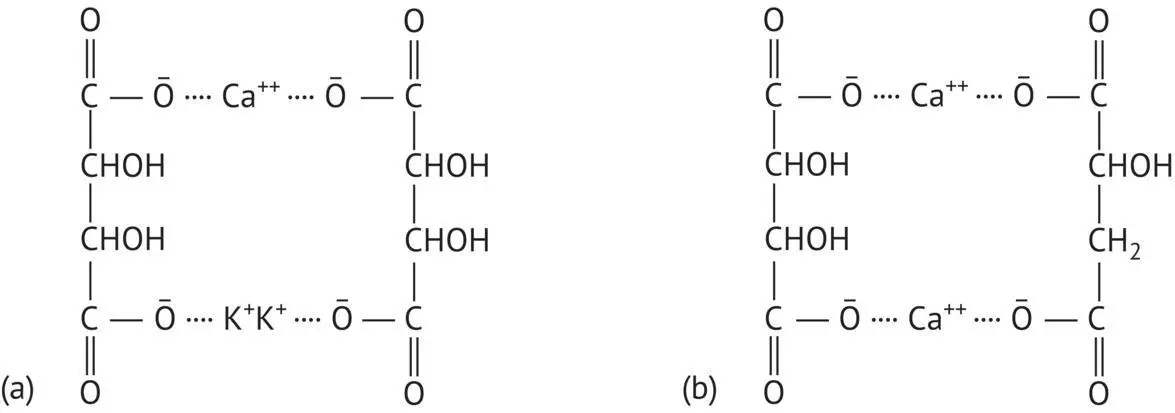

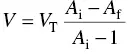

FIGURE 1.10 Structure of (a) potassium calcium double tartrate and (b) calcium tartromalate.

TABLE 1.11Solubility in Water at 20°C in Grams Per Liter of L‐Tartaric Acid and the Main Salts Present in Wine

| Tartaric acid |

Potassium bitartrate |

Neutral calcium tartrate |

| L(+)‐C 4H 6O 6 |

KHC 4H 4O 6 |

CaC 4H 4O 6·4H 2O |

| 4.9 g/l |

5.7 g/l |

0.53 g/l |

In wine, the simple salts are dissociated into HT −and T 2−ions. The two complex tartrate salts ( Figure 1.10) share the property of forming and remaining stable at a pH of over 4.5. On the other hand, in terms of solubility, they differ in that potassium calcium double tartrate is highly soluble, whereas the tartromalate is relatively insoluble and crystallizes in needles. The two properties of this mixed salt may be used to eliminate malic acid, either partially or totally ( Section 1.4.4). Table 1.11shows the solubility, in water at 20°C, of tartaric acid and the salts that cause the most problems in terms of crystalline deposits in wine.

Читать дальше