Ovid’s sources for the nearly two hundred and fifty stories that comprise his Metamorphoses span the history of Greek and Latin literature from Homer to his own time. Many date from the Hellenistic period, when mythological compendia such as Boios’ poem on bird metamorphoses and Nicander’s work on mythic transformations were popular. The poems of Callimachus provided inspiration as well. It is likely that Ovid used the lost work About Cyprus , by the geographer Philostephanus, for many of the myths in Book 10. He also used contemporary poems such as Vergil’s Aeneid and Cinna’s Myrrha , and perhaps two separate Metamorphoses , one by Parthenius and another by Theodorus. But Ovid was not a slavish copier of his sources. He created variants of myths that would allow his educated audience to make comparisons between traditional versions of these stories and his adaptations. Like Pygmalion, he fashioned raw material into something that was uniquely his.

Metamorphoses was completed shortly before Ovid’s exile. Although he burned his copy of the manuscript before departing for Tomis, he says that several others survived. Indeed, there were so many of them that Ovid asked that a preface be added that begged his audience’s pardon for the unpolished state of the poem ( Tristia 1.7.13–40). The sheer number of times that Metamorphoses was copied in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (nearly four hundred manuscripts survive today) testifies to its popularity throughout the ages.

Book 10 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses tells the story of the mythic bard Orpheus, whose wife died just after their wedding from the bite of a snake. Thereupon he travels to the underworld to persuade its rulers to release her. Pluto agrees, on the condition that he not look back at her until he reaches the earth. When Orpheus violates this agreement at the last possible moment, she is forced to return to the underworld, and he is denied a second chance to rescue her. Because of this tragic experience, he renounces the love of women and devotes himself to a life of pederasty. Orpheus expresses his attitude toward sexuality in a song that recounts various stories about the love of the gods for boys and the punishment meted out to women who indulged their illicit lusts. This song consists of the myths of Ganymede, Hyacinthus, the Cerastae, the Propoetides, Pygmalion, Myrrha, Venus and Adonis, and Atalanta and Hippomenes. Book 10 ends with the conclusion of Orpheus’ song; Book 11 begins with his death at the hands of the Thracian women and his subsequent reunion with Eurydice in the Elysian Fields.

The meter of English poetry is determined by the arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables:

Ón the Moúntains óf the Praírie,

Ón the greát Red Pípe-stone Quárry …

The meter of Latin poetry, by contrast, is determined by the arrangement of long and short syllables.

1 A syllable can be long by nature or long by position:A syllable that is long by nature contains a long vowel (lēgis) or a diphthong (arae).A syllable that is long by position contains a short vowel followed by two consonants (such groups include the sounds rendered by the letters “x” and “z,” namely “ks” and “ds”). These two consonants can occur in the same word (āttrāctam) or at the end of one word and the beginning of the next (fortēm virum). Note that “ch,” “ph,” and “th” do not count as two consonants because they represent the Greek letters χ, φ, and θ (Pērsĕphŏnēn). Moreover, an “h” at the beginning of the word does not make a vowel long by position (dĕŭs horum).

2 A short syllable contains a short vowel that has not been made long by position (e.g. tŏt aves).

3 A vowel followed by a consonant cluster consisting of a mute (b, c, d, f, g, p, t) and a liquid (l, r) can be counted either as a long or as a short syllable. For example, the word volucris appears twice at Metamorphoses 13.607. In the first instance, “u” is short; it is long in the second.

ēt prīmō sĭmĭlīs vŏlŭcrī, mōx vēră vŏlūcrīs .

Elisionoccurs when a word that ends in a vowel or in the case ending “-um,” “-am,” or “-em” is followed by a word that begins with a vowel or an “h.” When this happens, the vowel or the “-um,” “-am,” or “-em” drops out ( omn em hominem ).

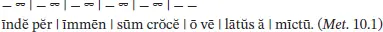

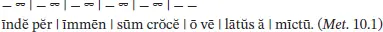

The meter of Ovid’s Metamorphoses is the meter of Greek and Latin epic: dactylic hexameter. It consists of six feet, which can contain dactyls (– ˘˘) or spondees (– –). A spondee may occur in any of the first four feet, the fifth foot is normally a dactyl, and the final foot is scanned as a spondee regardless of the quantity of the last syllable.

In contrast to Vergil, Ovid uses more dactyls than spondees (a ratio of 20 to 12), which allows his lines to move more rapidly than Vergil’s, whose cadence is generally graver. This befits Ovid’s tone, which is often playful and humorous. He also employs elision much less frequently than Vergil.

vi. Suggestions for Further Reading

1 Galinsky, G.K. 1975. Ovid’s Metamorphoses: An Introduction to the Basic Aspects. University of California Press: Berkeley.

2 Green, P. 1989. Classical Bearings. University of California Press: Berkeley.

3 Halporn, J., M. Ostwald, and T. Rosenmeyer. 1963. The Meters of Greek and Latin Poetry. Hackett: Indianapolis, IN.

4 Hardie, P. 2002. The Cambridge Companion to Ovid. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

5 Knox, P. 2009. A Companion to Ovid. Wiley Blackwell: Oxford.

6 Solodow, J. 1988. The World of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.

7 Weiden Boyd, B. 2002. Brill’s Companion to Ovid. Brill: Leiden.

AnaphoraThe repetition of a word at the beginning of successive lines or phrases. See lines 121–123.CaesuraA break between words within a foot. E.g. | īndĕ || pĕr |.ChiasmusThe repetition of a grammatical structure in reverse order. E.g. nunc arbor, puer ante (adverb–noun, noun–adverb).EmphasisThe use of a word that has both an obvious and an implicit meaning.EnjambmentThe continuation of a sentence or clause into the next line, often for emphasis. E.g. fessus in herbosa posuit sua corpora terra | cervus (128–129).Figura etymologicaThe use of two etymologically related words in close proximity to each other. E.g. voce vocatur.Hapax legomenonA word that occurs only once in the extant records of a language.HyperbatonThe separation of a noun from its adjective by several words.MetonymyThe substitution of an attribute or property for a related entity. E.g. the use of “crown” for “king.”ParataxisThe avoidance of subordinate clauses in favor of coordinate clauses.PleonasmThe use of more words than is necessary to convey an idea. E.g. muta silentia.ProlepticA reference to something that has not yet occurred. E.g. Pygmalion is called “Paphian hero” before his daughter, Paphos, has been born.Transferred epithetThis occurs when an adjective that describes one noun is transferred to another. E.g. copia digna procorum instead of copia dignorum procorum.TricolonThree parallel words or phrases in immediate succession. E.g. iam iuvenis, iam vir, iam se formosior ipso.ZeugmaA rhetorical device in which a literal and a figurative meaning are linked. E.g. hanc [feminam] simul et legem Rhodopeius accipit heros.

Читать дальше