Initiate the clinical exam by confirming the presence of typical anatomical features by performing a thorough extraoral and intraoral examination, further investigating any deviation from normal. Assess the stability of the temporomandibular joint, checking for repeatability of occlusion and an absence of pain upon loading the temporomandibular joint. Be sure to palpate the muscles of mastication and associated local lymph nodes, checking for any swelling or tenderness. Additionally, record the patient's maximum pain‐free opening, assessing the range of motion and determining if there is sufficient room for any required surgical instrumentation and access.

Once this has been completed, begin your focused exam pertaining to the patient's chief complaint. Identify local or regional anatomical structures that may become involved in the course of surgical or prosthetic treatment being planned for the individual. Consider appropriate pain management techniques for the planned surgery via delivery of local anaesthetic to the local innervation. Carefully plan any incisions required for surgical access with respect to any local vital structures.

Conduct your patient assessment in an organised fashion, starting externally and then working your way to the oral cavity and site in question.

Develop an organised approach to patient anatomical assessment to increase efficiency and repeatability.

Pay particular attention to the patient's ability to open, and their ability to stay open during a potentially longer procedure, to determine if the patient is a candidate for surgery or if other accommodations may be required.

Develop a surgical plan for local anaesthetic and incision design. Familiarise yourself with the local vital structures that may be encountered during surgery.

Determine if any specialised testing, imaging, or additional referrals are required to confirm patient suitability for implant surgery.

1 1 Norton, N. (2007). Netter's Head and Neck Anatomy for Dentistry. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier.

2 2 Al‐Faraje, L. (2013). Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy for Oral Implantology. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co.

7 Maxillary Anatomical Structures

Kyle D. Hogg

An understanding of the anatomical structures of the maxilla relevant to oral implantology is a prerequisite for providing safe and predictable surgical treatment. Thorough pre‐operative planning and review of important regional anatomy in should be performed at the treatment planning stage in advance of implant placement to avoid both surgical and prosthetic complications.

Anterior Maxilla

Maxillary incisive foramen and canal

Nasal cavity

Infraorbital foramen

Posterior Maxilla

Maxillary sinus

Greater palatine artery and nerve.

7.2 Maxillary Incisive Foramen and Canal

The maxillary incisive foramen is located at the midline of the inferior surface of the maxillary palatal process approximately 10 mm behind the mesial incisal edges of the central incisor clinical crowns. This foramen is the opening to the incisive canal, which carries bundles of the nasopalatine nerve and the anterior branches of the greater palatine artery, both sourced bilaterally [1]. The incisive canal is approximately 11 mm long, with the incisive foramen located inferiorly possessing a mean diameter of 4.5 mm that tapers to about 3.4 mm at the level of the nasal floor superiorly [2].

The nasopalatine nerve is a branch of the posterior superior nasal nerves arising from the pterygopalatine ganglion branch of the maxillary nerve (CN V2). This nerve courses inferiorly and anteriorly, passing through the incisive foramen, where it supplies innervation to the anterior part of the palate, before ultimately communicating with the greater palatine nerve. Thus, local anaesthesia delivered to the incisive foramen may be utilised when performing surgical procedures or operative dentistry in the region of the anterior maxilla.

The anterior branch of the greater palatine artery branches off the greater palatine artery after it emerges from the greater palatine foramen in the posterior palate and runs anteriorly across the hard palate towards the incisive foramen. Once it passes through the incisive canal, the anterior branch of the greater palatine artery anastomoses with the sphenopalatine artery on the nasal septum or in the region of the canal itself.

7.2.1 Importance in Oral Implantology

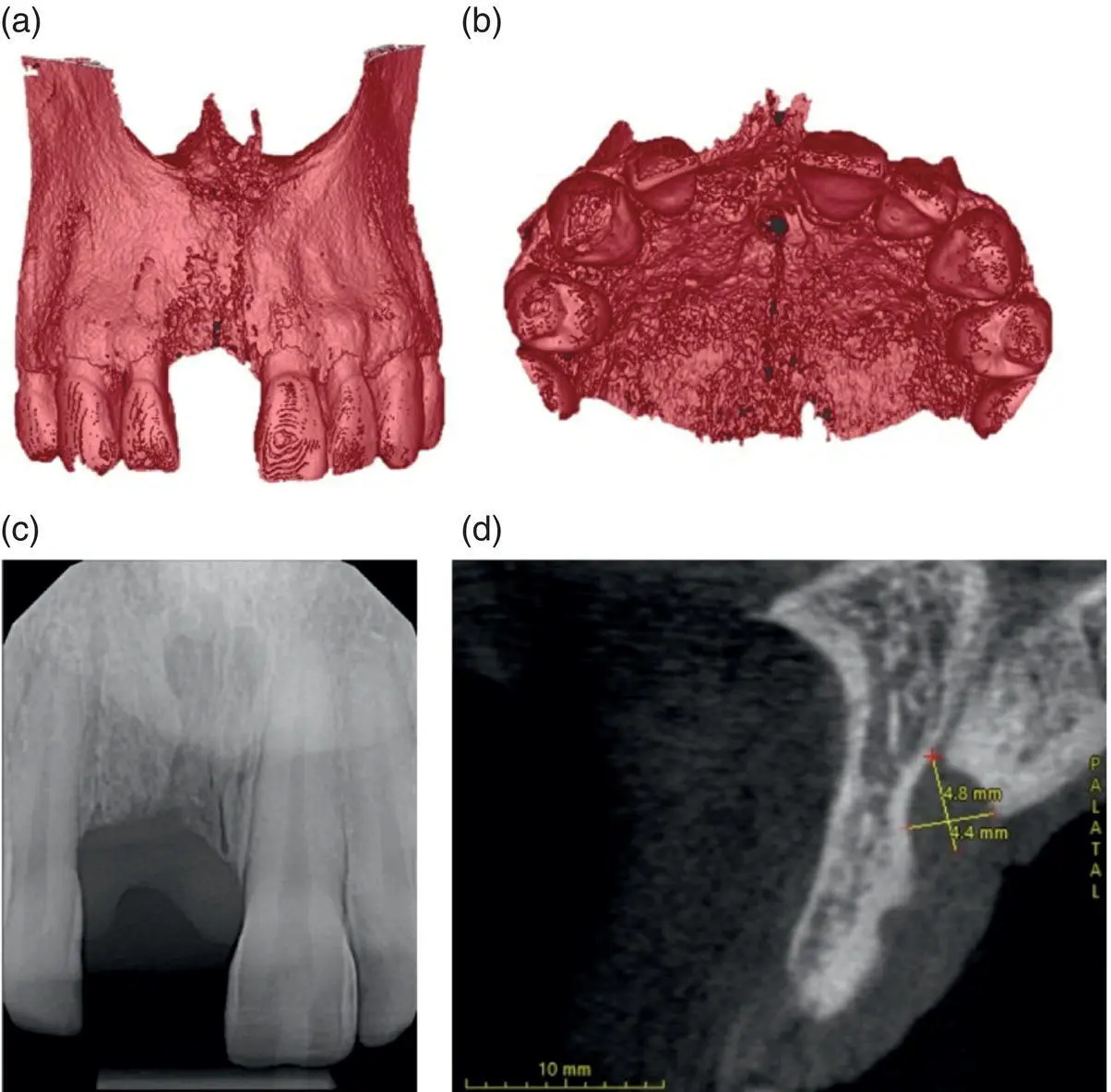

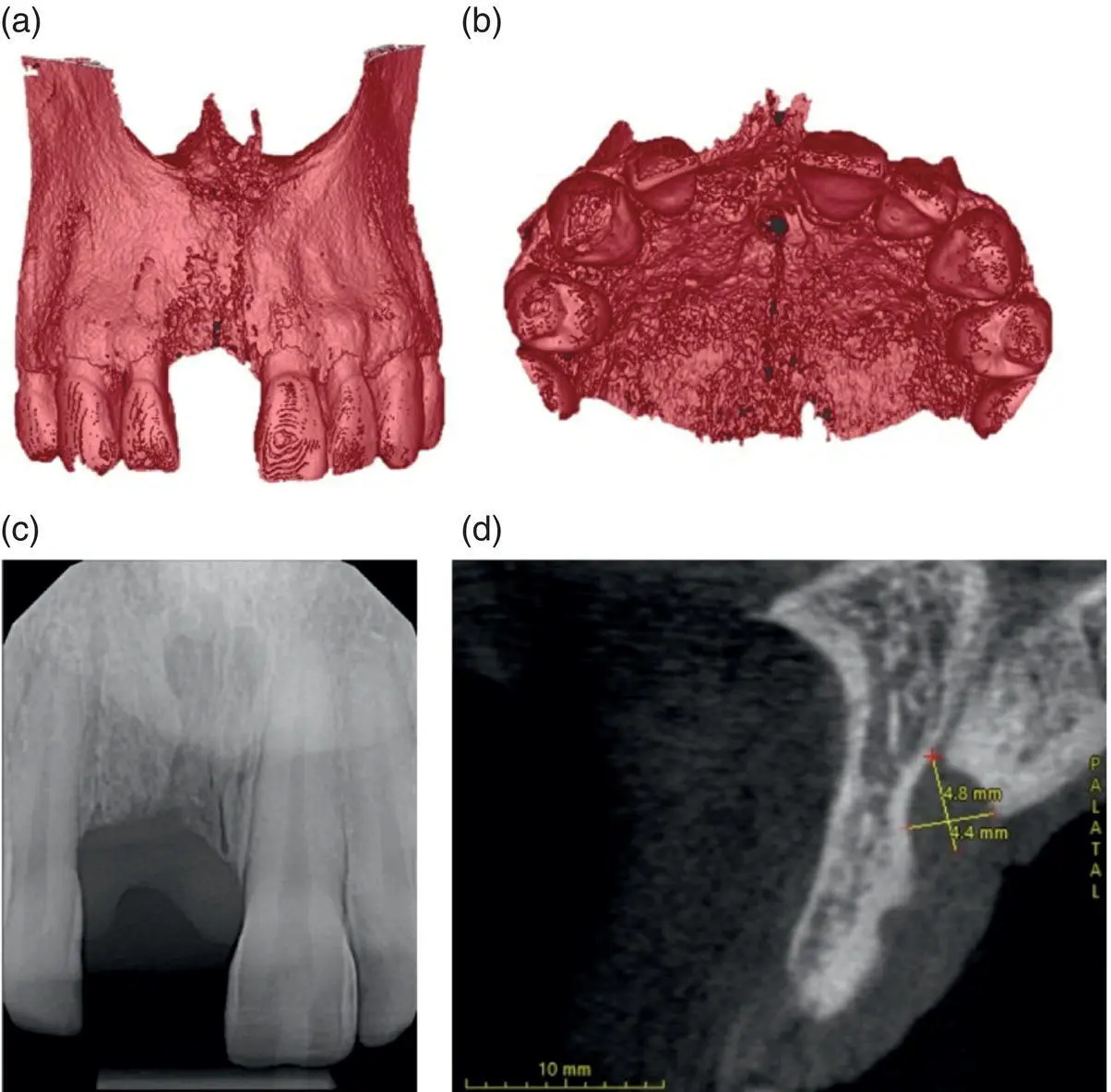

While the incisive foramen and canal are seldom selected as a site for placement of a dental implant these anatomical features can limit the bone volume available for implant placement in the anterior maxilla, specifically the central incisors. This can be a common occurrence in patients with a resorbed maxillary alveolar process secondary to tooth loss. In these individuals the distance in the sagittal plane between the anterior border of the incisive foramen and canal and the buccal plate of the anterior maxilla is often reduced in comparison with subjects that are dentate in this region. The incisive foramen and canal are positioned proximal to the confluence of the nasal septum, nasal floor, anterior nasal spine, and hard palate when viewed from the frontal plane. The complex bony architecture in this region limits the effectiveness of pre‐operative evaluation using traditional two‐dimensional periapical radiographs. Three‐dimensional imaging via cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans provide more accurate assessment of both foramen and canal morphology, which can vary significantly [3], and allow for evaluation of available bone volume.

At times, the location and morphology of the incisive foramen and canal may prevent placement of dental implants in the position of the maxillary central incisors, as seen in the clinical case highlighted in Figure 7.1. If the proposed treatment does not permit the selection of alternative suitable sites for dental implant placement guided bone regeneration (GBR) techniques may be required to augment the bone volume anterior to the border of the canal to facilitate implant placement in that area. The incisive canal itself can be grafted in a procedure called incisive canal deflation to provide further bone volume for subsequent implant placement. This technique can be performed under local anaesthetic with reflection of a full‐thickness flap raised, permitting access for complete removal of canal contents via rotary curettage. The canal can then be grafted with particulate bone without long‐term ill‐effects to the patient [4, 5]. While a transient loss of sensation in the anterior maxillary palatal area is possible, the revascularisation and reinnervation of the region due to the anastomoses with the greater palatine artery and nerve typically return sensation within several months.

Figure 7.1 Three‐dimensional versus two‐dimensional view of incisive foramen. A CBCT scan can provide invaluable information about the true anatomical relationship between the incisive foramen and the proposed site for a dental implant. The 3D reconstruction from the CBCT scan depicted in (a) and (b) allows for a more accurate assessment of the edentulous site when compared to the 2D periapical radiograph (c). The sagittal slice (d) shows the enlarged foramen.

The inferior border of the nasal cavity is relevant to oral implantology due to its proximity to the oral cavity and tooth root apices. It consists of the anterior nasal spine and the maxillary alveolar process located anterior to the incisive canal and the hard palate or palatine process of the maxilla and horizontal plate of the palatine bone posterior to the incisive canal, when viewed sagittally through the midline. The nasal cavity provides the superior limit to the volume of the maxillary alveolar process available in the anterior region for implant placement, with the buccal plate providing the anterior limit while the palatal plate or incisive canal provides the posterior limit.

Читать дальше