1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...47 The practice of twenty‐first century medicine and surgery exists within a data‐driven world. To that end, all chapters are updated in terms of new references and many meta‐analyses/systematic reviews are reviewed in the spirit of supporting evidence‐based practice. New cases have been added to most chapters to illustrate important points. Algorithms continue to be offered to assist clinicians in decision‐making processes associated with the management of salivary gland pathology. Most chapters also contain a new teaching element – case presentations that serve to illustrate and reinforce essential take‐home messages either suggested or emphasized in their respective chapters. Finally, videos of salivary gland surgical procedures are included in the chapter devoted to innovative salivary gland surgery in this third edition.

As with the first and second editions of this textbook, it is our expressed purpose to brand this third edition a singular reference with extensive text and clinical images. It is our hope that this textbook will provide a useful update to our international colleagues and their patients who benefited from the prior editions.

Eric R. Carlson, DMD, MD, EdM, FACS

Robert A. Ord, BDS, MB BCh (Hons), FRCS, FACS, MS, MBA

I would like to thank my teachers, residents, fellows, and patients for their trust, encouragement, wisdom, and inspiration. I am grateful to all of you.

Eric R. Carlson

To my wife, Sue, my inspiration as always.

Robert A. Ord

About the Companion Website

Don’t forget to visit the companion web site for this book:

www.wiley.com/go/carlson/salivary

There you will find valuable materials, including:

Videos

Scan this QR code to visit the companion website:

Chapter 1 Surgical Anatomy, Embryology, and Physiology of the Salivary Glands

John D. Langdon, FKC, MB BS, BDS, MDS, FDSRCS, FRCS, FMedSci

Emeritus Professor of Maxillofacial Surgery King’s College London, England

Introduction

Parotid Gland Embryology Anatomy Contents of the Parotid Gland Facial Nerve Auriculotemporal Nerve Retromandibular Vein External Carotid Artery Parotid Lymph Nodes Parotid Duct Nerve Supply to the Parotid

Submandibular Gland Embryology Anatomy Superficial Lobe Deep Lobe Submandibular Duct Blood Supply and Lymphatic Drainage Nerve Supply to the Submandibular Gland Parasympathetic innervation Sympathetic innervation Sensory innervation

Sublingual Gland Embryology Anatomy Sublingual Ducts Blood Supply, Innervations, and Lymphatic Drainage

Minor Salivary Glands

Tubarial Salivary Glands

Histology of the Salivary Glands

Control of Salivation

Summary

Case Presentation – Wait, What?

References

There are three pairs of major salivary glands consisting of the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands. In addition, there are numerous minor glands distributed throughout the oral cavity within the mucosa and submucosa.

On average, about 1.5 l of saliva are produced each day but the rate varies throughout the day. At rest, about 0.3 ml/min is produced but this rises to 2.0 ml/min with stimulation. The contribution from each gland also varies. At rest, the parotid produces 20%, the submandibular gland 65%, and the sublingual and minor glands 15%. On stimulation, the parotid secretion rises to 50%. The nature of the secretion also varies from gland to gland. Parotid secretions are almost exclusively serous, the submandibular secretions are mixed, and the sublingual and minor gland secretions are predominantly mucinous.

Saliva is essential for mucosal lubrication, speech, and swallowing. It also performs an essential buffering role that influences demineralization of teeth as part of the carious process. When there is a marked deficiency in saliva production, xerostomia, rampant caries, and destructive periodontal disease ensues. Various digestive enzymes – salivary amylase – and antimicrobial agents – IgA, lysozyme, and lactoferrin – are also secreted with the saliva.

The parotid glands develop as a thickening of the epithelium in the cheek of the oral cavity in the 15 mm Crown Rump length embryo (sixth week of intrauterine life) (Zhang et al. 2010; Berta et al. 2013; Chadi et al. 2017). This thickening extends backward toward the ear in a plane superficial to the developing facial nerve. The deep aspect of the developing parotid gland produces bud‐like projections between the branches of the facial nerve in the third month of intrauterine life. These projections then merge to form the deep lobe of the parotid gland. By the sixth month of intrauterine life, the gland is completely canalized. Although not embryologically a bilobed structure, the parotid comes to form a larger (80%) superficial lobe and a smaller (20%) deep lobe joined by an isthmus between the two major divisions of the facial nerve. The branches of the nerve lie between these lobes invested in loose connective tissue. This observation is vital in the understanding of the anatomy of the facial nerve and surgery in this region (Berkovitz et al. 2003).

The parotid is the largest of the major salivary glands. It is a compound, tubuloacinar, merocrine, exocrine gland. In the adult, the gland is composed entirely of serous acini.

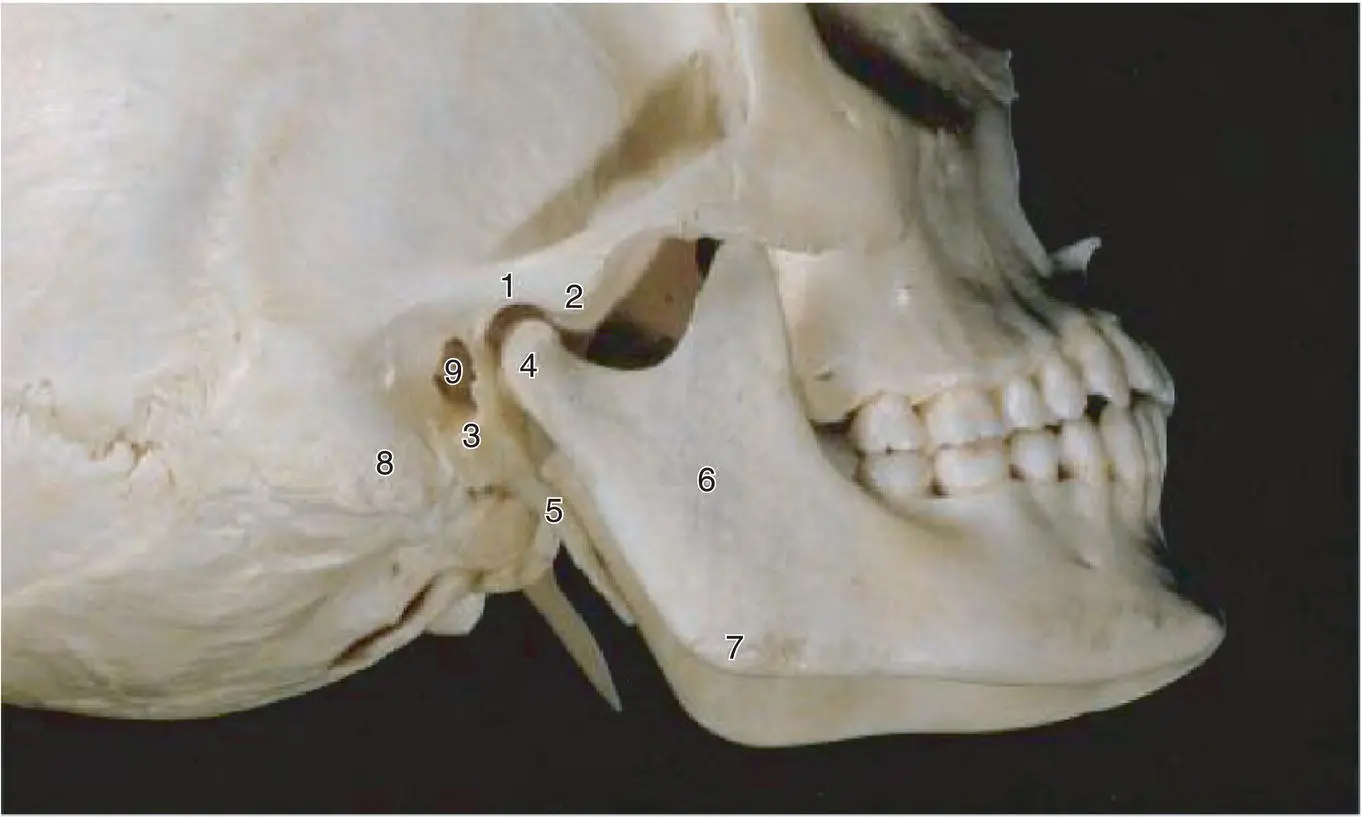

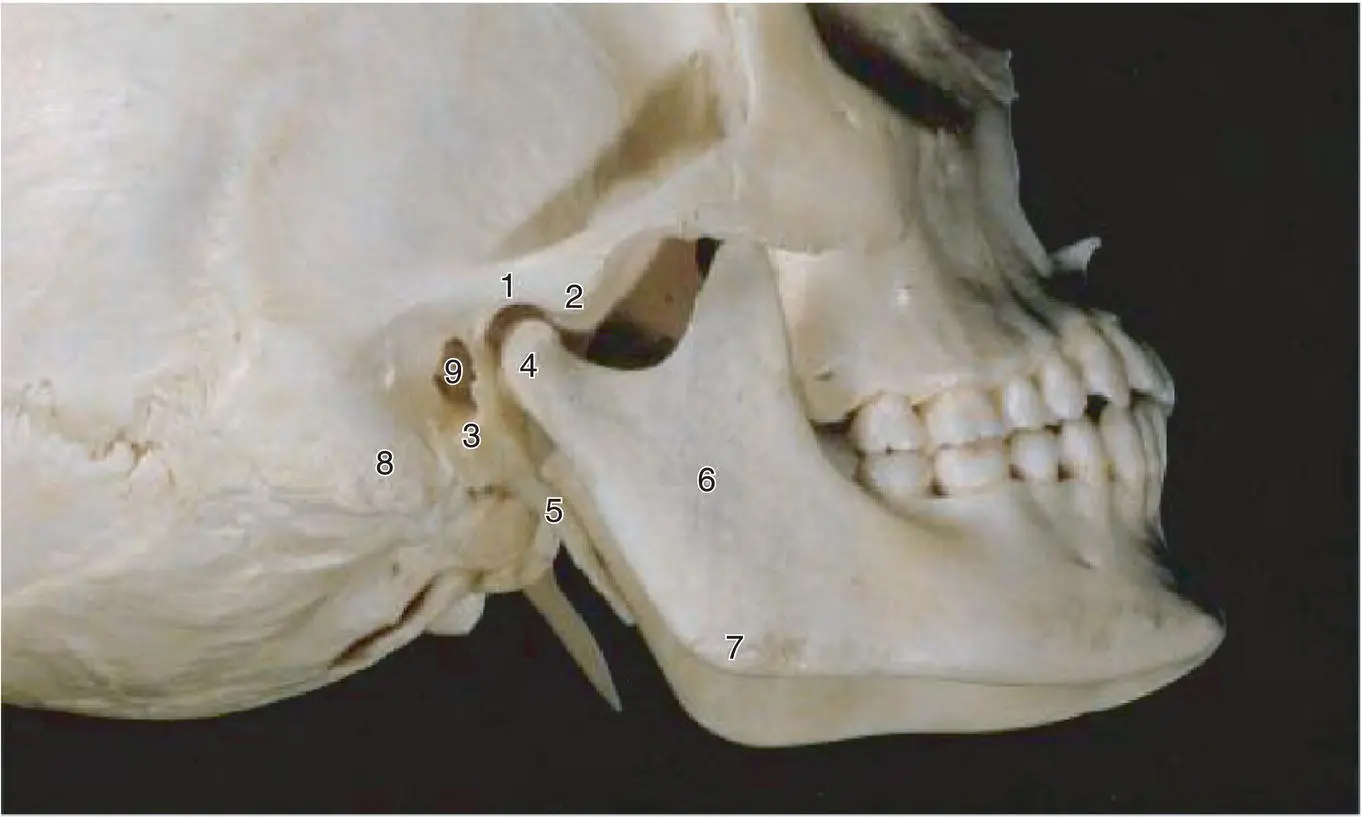

The gland is situated in the space between the posterior border of the mandibular ramus and the mastoid process of the temporal bone. The external acoustic meatus and the glenoid fossa lie above together with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone ( Figure 1.1). On its deep (medial) aspect lies the styloid process of the temporal bone. Inferiorly, the parotid frequently overlaps the angle of the mandible and its deep surface overlies the transverse process of the atlas vertebra.

Figure 1.1. A lateral view of the skull showing some of the bony features related to the bed of the parotid gland.

Source: Published with permission, Martin Dunitz, London, Langdon JD, Berkowitz BKB, Moxham BJ, editors, Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa. DOI: 10.1002/9781118949139.ch1.

Читать дальше