FIG 1-11 Seeing a person through the ages. In this case at 24 months, 17 years, and 65 years, respectively. Proportionally, the small mandible is eternal. Understanding why small mandibles are so common, and their link to dental crowding, bad bites, and airway obstruction, is a primary subject of this book.

This model was built by merging data from real CT scans, precise anatomical segmentations of hard and soft tissues, and a lifetime of study involving many thousands of people to determine the interlinks between facial profile, airway, jaws, and occlusion. Peppered among these illustrations are real examples of actual patients and procedures that best illustrate my concepts that underlie both facial surgical and orthodontic diagnosis, as well as the comparative therapeutic and cosmetic benefits of this treatment or that.

For instance, the illustrations explaining the mechanism of thumb sucking were directly derived from the volumetric scans of a real infant who had developed anterior open bite. The images were donated by a Sydney-based radiology house who had examined an intubated child in a Sydney-based pediatric-care ICU. He had developed life-threatening suppurant pansinusitis following advice to his mother to actively cease his thumb sucking habit.

CT scans of infants are profoundly rare. But with this single image set came our first proof of the importance of nasal breathing to developing a normal healthy state of the nasal sinuses. With it too came an understanding of the developmental compromise committed upon the maxilla and sinuses by the small mandible and glossoptosis, as well as the contribution that normal nasal breathing gave to normal midfacial development. It also pointed out to us that dental advice that demonizes thumb sucking in order to prevent the development of anterior open bite was harmful in that it deleted the “why” the child was thumb sucking in the first place.

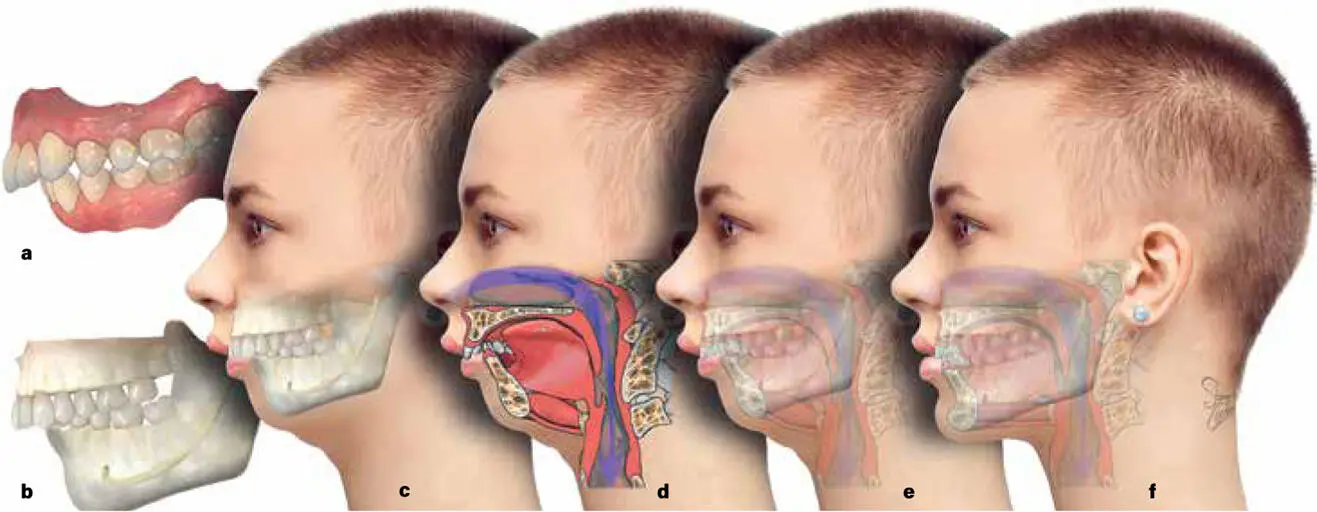

Another illustration base focused on a single midadolescent female and the effect that IMDO had upon correcting her Class II malocclusion and in normalizing her small mandible. It was through this patient that we precisely studied the effects of tongue muscle pull, particularly the geniohyoid muscle, and its relief upon glossoptosis. These CT scans were painstakingly rendered in 3D to accurately demonstrate the multiple dental, facial, and airway issues associated with anterior mandibular hypoplasia (AMHypo).

There is very little that differentiates one human from another. The tiny genetic differences that distinguish a Finn from a native Peruvian would account for less than 0.0001% of the entire human genome. Yet it is in the expression of this tiny genetic difference that we examine all that is different between ourselves, or groups of ourselves. In studying faces and jaws and bites, what we are looking for is a common fundamental link that gives the human commonality for all the various patterns of dental crowding and the connected link to inner airways and overlying facial form. And it is through these same illustrations that we can examine the effects of bespoke facial design that augments the therapeutic facial surgical intervention—six ways.

ORTHODONTIC CLASSIFICATIONS OF MALOCCLUSION

Malocclusion is a dental term, and it relates to the teeth alone. The Angle classification was invented before we had radiographs or CT scans or even a modern understanding of functional facial anatomy. As such, the Angle classification of malocclusion is outdated and, frankly, not useful to a description of orthognathics. More importantly, this classification is exclusionary in that it does not define why the condition of malocclusion exists. By only looking at teeth, the Angle classification inherently excludes any understanding of the volume effects of jaws, particularly their effect on facial profiles, the postural effects on the tongue, and the overall lifetime effects of the compromised inner airway.

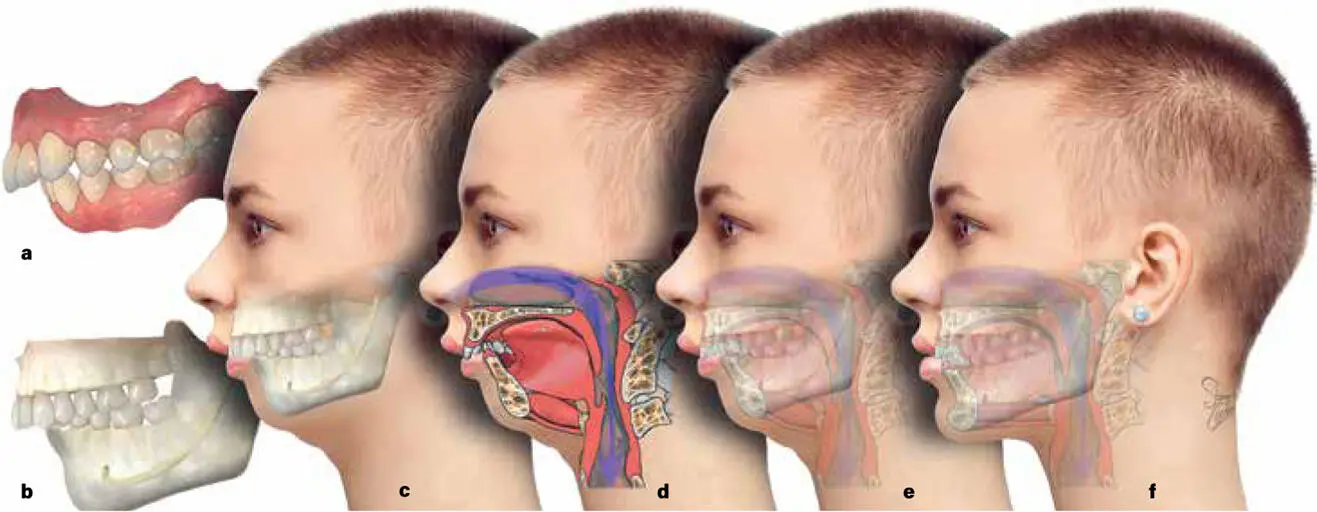

In my worldview, there are six methods for looking at malocclusion in profile ( Fig 1-12). First, you can look at the teeth and gingiva and their intra-arch relationship. Second, you can look at how the malocclusion state relates to the underlying local dental skeleton. Third, you can look at how the dental skeleton and bite relate to the profile of the face. Fourth, you can look at how the whole facial skeleton relates to the inner airway. Fifth, you can look at the way the occlusion, skeleton, face, and airway combine simultaneously. And finally, you can look at the way that a given therapy affects all four anatomical states in terms of dynamic posture (asleep vs awake, smiling vs relaxed, supine vs erect).

FIG 1-12 How various anatomical layers are interpreted. (a) View of how a dentist, parent, or orthodontist may see the relationship of maxillary and mandibular teeth in the mouth, or within an intraoral photograph. The patient may hold the mandible forward, altering the true bite relationship, but this visual oral examination is blind to jaw joint position. (b) A radiograph such as an OPG or even a lateral cephalogram gives little obvious further elaboration upon the visual beyond an examination of tooth roots, or at best the mandibular outline. There is no true elaboration on jaw joints, neutral jaw joint seating, or the overlying face itself. (c) The skeletal, dental, and facial relationships can be married, but this view still ignores the internal. (d) Cross-sectional views help understand toned (awake) tongue muscle contraction and airway patency. (e) Fusion of all pretreatment elements allows us to see the combined awake and erect relationships of the tongue, jaws, teeth, occlusion, airway, jaw joints, and facial effects that combine as a result of the small mandible. (f) The directed surgical treatment of part c to fundamentally correct the mandibular volume demonstrates a comparative means of seeing how dental impactions, malocclusion, airway collapse, tongue contraction, and facial profile may change toward an ideal anatomical state.

Considering the different orthodontic classifications for malocclusion, this chapter presents 1:1 illustrations (see Figs 1-13to 1-16) to demonstrate that all forms of common malocclusion are derived from the same basic common smallness of the mandible, or what I call anterior mandibular hypoplasia (AMHypo). Illustrations are made with a chin button (normogenia) or without a chin button (agenia), but note that almost all people with AMHypo also have some form of agenia. You will notice that those who have a chin button have a subtly greater pull on the geniohyoid muscle, with slightly greater patency of the airway behind the epiglottis (the so-called C3ERPO point, or 3rd Cervical, upper Epiglottic, Retropharyngeal Obstruction point), and slightly more defined chin-neck contour. This may indicate a view that the natural chin button has an evolutionary function in stretching the geniohyoid to help overcome glossoptosis, but this is not my opinion. I honestly do not know why some humans have chin buttons, except that they look good. My therapeutic opinion is that the surgical GenioPaully, which creates a chin button, does have these therapeutic airway effects, as well as a primary effect on the lower lip posture, lip competency, and general esthetic lines that are drawn.

Which profile the patient displays, and which treatment philosophy you choose, will define everything that will follow. The only fundamental differences are whether there is agenia or not, AMHypo or not, and maxillary hypoplasia or not.

Читать дальше