Dental orthopantomogram (OPG; Fig 1-2) analysis, also known as panoramic radiography , allows a better assessment of the teeth and mandible, but it is a highly distorted view. Even used together, panoramic radiography and lateral cephalometry are still poor descriptors of jaw and facial volumes and proportionality, and they are completely inadequate in assessing both airways and faces ( Fig 1-4).

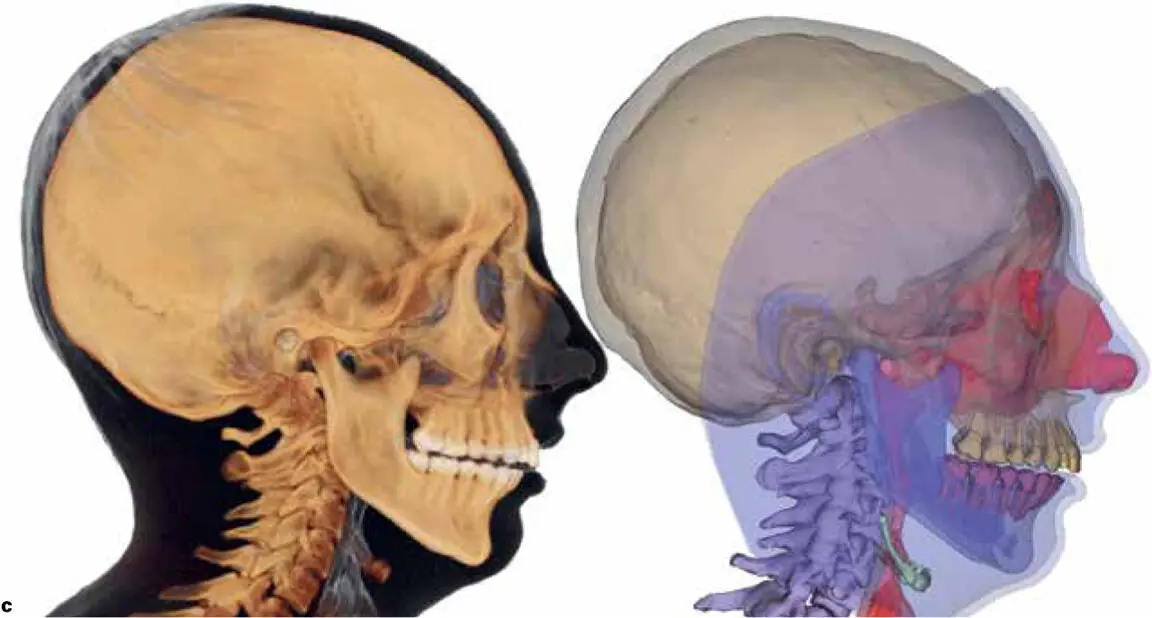

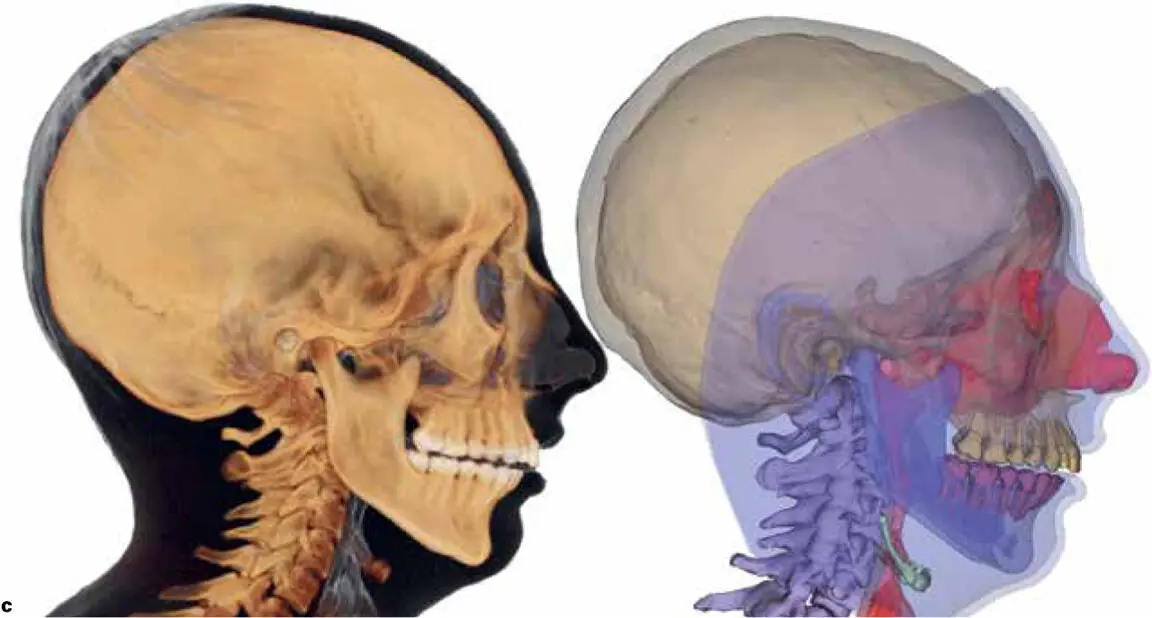

FIG 1-4 A better way than lateral cephalometry is to assess the interplay of teeth and bone as volumes in three dimensions. But this hard tissue 3D view does not see the soft tissues, and it does not visualize the airway or those anatomical structures that influence it. The competition of the dental perspective, which sees excessive and crowded teeth that together form a malocclusion, versus the medical perspective, which sees small jaw volumes and compromised airways and altered facial form, catches the parent between complex philosophical arguments. The crystal clear alternatives are divided as (1) traditional camouflage orthodontics based on dental extractions (including third molars) and (2) early interventional surgery through the intermolar mandibular distraction osteogenesis (IMDO) protocol. The winner or loser of that choice can only ever be the child and future adult.

Yet the extrapolation from dental radiographic analysis to dental clinical pathway persists because it is formalized. Parents believe it to be true, and of course dental professionals believe it to be true. We all collectively and repeatably participate. The orthodontic waiting room is full of kids with braces and elastics. Our society is convinced that braces and dental extractions and orthodontics are all noninvasive and essentially benign and normal processes. But what we potentially ignore is the obvious fact that the 12-year-old sitting in front of us now will be an adult later on ( Fig 1-5). And all of the dental analysis that is geared toward directing an adolescent orthodontic process, a process centered only on the negative esthetic of big anterior teeth, intrinsically ignores the biggest issue of them all—the ongoing lifetime effects, which started at birth and will end in old age, of what caused the bad bites and dental crowding and permanent tooth impactions to occur in the first place: the small mandible.

FIG 1-5 This patient had been treated with orthodontic bite splints and expert nonextraction camouflage orthodontics since the age of 12 years for a significant dental overjet and severe dental crowding. (a) At age 20 years, after having her third molars removed, she presented with complaints of significant breathing issues, general exercise intolerance, and a chronic forward head posture that she found impossible to correct by “standing up straight.” While she had not yet developed full obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), she knew she snored, and she knew her small mandible had a big part to play in the history of her issues. For this patient, remedial jaw surgery coupled with repeat orthodontics offered a significant chance of permanent cure for her airway, bite, and posture problems. (b) With her jaw seated anatomically in its natural joint positions, her teeth only met at the back of her mouth, with a significant anterior open bite. The forward head posture and poor chin-neck contour are significant esthetic concerns. (c) Digitally derived lateral cephalometry with medical computed tomography (CT) or dental CBCT has significantly evolved from the traditional plain x-ray machine. Segmentation of color rendering allows for clear visualization of teeth, jaws, airway, and cervical posture. Such rendering not only improves diagnostic performance for the dentist but also helps the patient understand the complex interlinks of airway, bite, skeleton, and face. In this case, even with extreme forward head positioning, forward collapse of the cervical spine is still pushing into the back of the tongue, significantly reducing airway lumen and causing pronounced airway obstruction during sleep and during erect exercise.

DENTAL EXTRACTIONS AND TRADITIONAL ORTHODONTICS

Almost all humans have the genetic potential to develop and keep 32 adult teeth. But almost all adolescents have dental crowding as their adult dentition erupts, giving the visual illusion that there are an excessive number of adult teeth. And almost all adolescents with dental crowding will develop impactions of the third molars; this near-universal impaction in people with crowded teeth gives an illusion that third molars are redundant or evolutionarily unnecessary to modern human existence. Because we have people in modern society whose craft it is to treat this human commonality of dental crowding, if a child with crowded teeth has a mother wanting to treat that crowding or crookedness with classical orthodontics, then braces combined with dental extractions of any of those 32 adult teeth through oral surgery is inevitable.

Crowded or overly prominent anterior teeth, or any bad bite (whether Class I, II, or III) for that matter, usually results in premolar extractions ( Fig 1-6). While this is considered “minor oral surgery” because it is performed in-office by the dentist, it is by no means “minor” to the individual losing these teeth. Combine this with third molar removal, and a given orthodontic patient is losing a minimum of six to eight permanent teeth. Even if “nonextraction” treatment is selected in clinical orthodontics (Fig 1-7), third molar removal is still almost universally required. So if an adolescent has dental crowding, or a malocclusion, or dental impactions, or all of these together, then dental extractions carry an almost 100% certainty in late adolescence or early adulthood.

FIG 1-6 Extracting premolars to create dental space for orthodontic decrowding, or retraction of prominent anterior teeth, is the basis for all camouflage orthodontics used for the treatment of Class II, division 1 malocculsion.

FIG 1-7A For Class II, division 1 malocculusion, not extracting premolars requires expansion and then orthodontic retraction of prominent anterior teeth as the created midline gap is closed. This backward retraction further potentiates the chance of maxillary third molar impactions. How this combination or pattern of orthodontics ultimately leads to other facial and airway effects is described in chapter 12.

FIG 1-7B The process of expansion and retraction of prominent anterior teeth produces an elongation and vertically excessive “gumminess” to the anterior teeth and accentuates the original lip incompetence associated with the small mandible. This pattern of camouflage orthodontics is a leading cosmetic drive and preamble to later remedial BIMAX surgery. This patient’s treatment is explained in Fig 15-14.

Читать дальше